The EconTalk podcast episode that Russ Roberts did with David Epstein, author of The Sports Gene, which I encouraged you to listen to last year, wound up tied for best show of 2013 in a listener vote. If you missed it and want to catch up, go here.

In the latest program, Roberts interviews Moises Velasquez-Manoff, author of An Epidemic of Absence, which examines whether what’s purported to be a sharp spike in autoimmune diseases and allergies in America has been caused by our fervent efforts to cleanse ourselves of parasites and worms. The Food and Drug Administration is considering treatments in which these organisms would be purposely introduced into patients. The host and guest discuss an underground scene that isn’t waiting for FDA approval, in which medicalized hookworms and such are being injected into the sick who wish to gamble on this counter-intuitive medicine.

As a layman, it’s difficult to process any of this without thinking about the recent furor about immunizations in which junk science convinced some citizens that inoculations caused autism. And even more recently, the supposed advantage of breast feeding over bottle feeding, which has since been largely debunked, changed actual childcare policy in New York City. You have to wonder how much the increase in allergies and autoimmune diseases is the result of better statistical information about the incidences of these illnesses. And even if the rise is legitimate, there obviously could be a multitude of causes.

Listen to the podcast here. An excerpt about the so-called “worm therapy” underground:

“Russ Roberts:

So, let’s talk about the hookworm underground and how it got started. Tell us what it is, this phenomenon of people injecting themselves deliberately with various types of parasites and why did anyone start to think that was a good idea?

Moises Velasquez-Manoff:

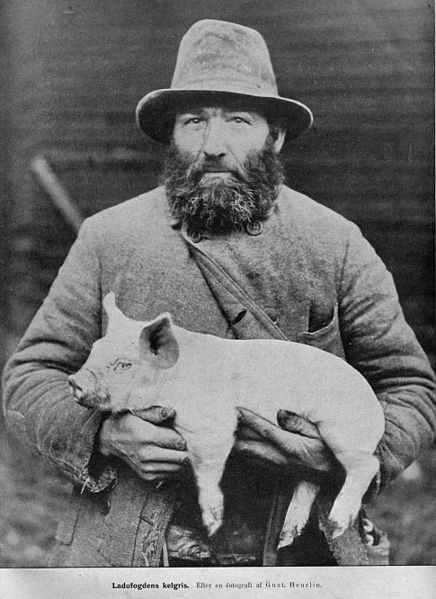

Yes. Well, back up. So, in the 1990s, people started thinking about some of the parasite questions I’ve been talking about. Mostly because they understood the immunology. And they understood that parasites suppress the immune system. And they began–and they noticed also some populations that were parasitized, these diseases were far less prevalent. So they began to think: Well, how about we deliberately introduce parasites as a way to cure some of these diseases? It’s an outrageous idea. But then a gastroenterologist named Joel Weinstock, who is now at Tufts U., developed a parasite, and medicalized it so it was in theory safe. The parasite is native to pigs. And the reason he chose this parasite is it cannot reproduce sexually in humans. So that you give it to the person and no one else gets it. That’s the idea. The context, the historical context, is: we spent lots of money in this country getting rid of parasites. The last thing you want to do is reintroduce them to the population, right?

Russ Roberts:

And you talk about how, when people would suggest these transmission mechanisms for allergies and autoimmune problems, the outrage that many in the medical profession, in the fields of science had to the idea that there was something beneficial about this scourge that we had eliminated.

Moises Velasquez-ManofF:

Yeah!

Russ Roberts:

It’s hard to–it’s difficult to accept. It’s emotionally unpleasant. But intellectually, it’s deeply disturbing. It’s like being told: Oh, we always were told to wash our hands, that that’s good for you. And doctors really should wash their hands. But it turns out maybe, sometimes, dirty hands are good for you. That’s horrifying.

Moises Velasquez-ManofF:

Right.

Russ Roberts:

As you say, it’s outrageous. So, what happened with this pig worm?

Moises Velasquez-ManofF:

So, he developed it–this is actually in testing right now for FDA (Federal Drug Administration) approval; and I should point out that some of the results–the early results were amazing. They were so impressive. It was like 3 dozen people and a 75% remission rate for Crohn’s Disease. It was unbelievable. And now it’s in testing. And some of the results have been very lackluster, so far. So we don’t really know if it works yet. But in any case, a bunch of underground people are reading this science. I mean, this is published in reputable journals. It makes sense to a certain kind of mindset that’s kind of ecologically and holistically oriented.

Russ Roberts:

And if you have a chronic disease, you’d love to try something different, if whatever you’ve been trying isn’t working reasonably. Right?

Moises Velasquez-ManofF:

Absolutely. I mean, I think actually at some point it’s a rational–it’s a very rational choice.”