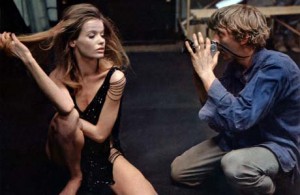

Michelangelo Antonioni was great at many things, but he never filmed sex or dance convincingly. Why was that? Self-consciousness? Guilt? In 1970, at the time of his remarkably infamous film, Zabriskie Point, the director was given the cover treatment by Look. An excerpt from the article:

“When Blow-Up became a money-maker in the U.S., Antonioni had a prompt invitation from MGM to do a film here. Partly because of Antonioni’s temperamental reputation, MGM officials kept their distance. He went to the Chicago convention (where he was Maced), SDS meetings and the Free Church at Berkeley, arousing suspicions in some vigilant quarters that he might be going to emphasize the trouble spots of America. MGM still claims it doesn’t know what Zabriskie Point, an expensive production, is all about.

Antonioni worked on his script with two young American writers, Sam Shepard and Fred Gardner. No one was permitted to discuss the ever-changing plot (‘political events go by too fast for the cinema to keep up’). His company never knew where they would work the following day. Press agents and crew members, unused to his impromptu methods, were fired.

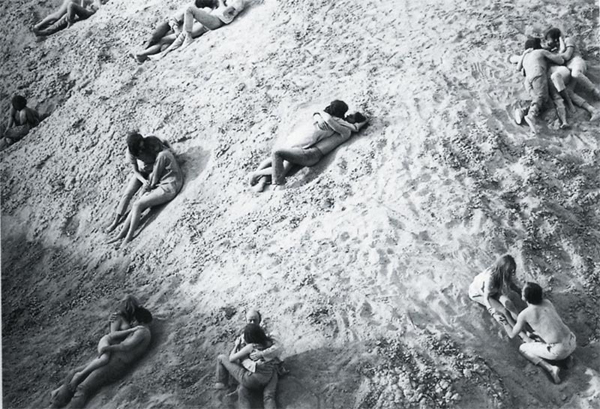

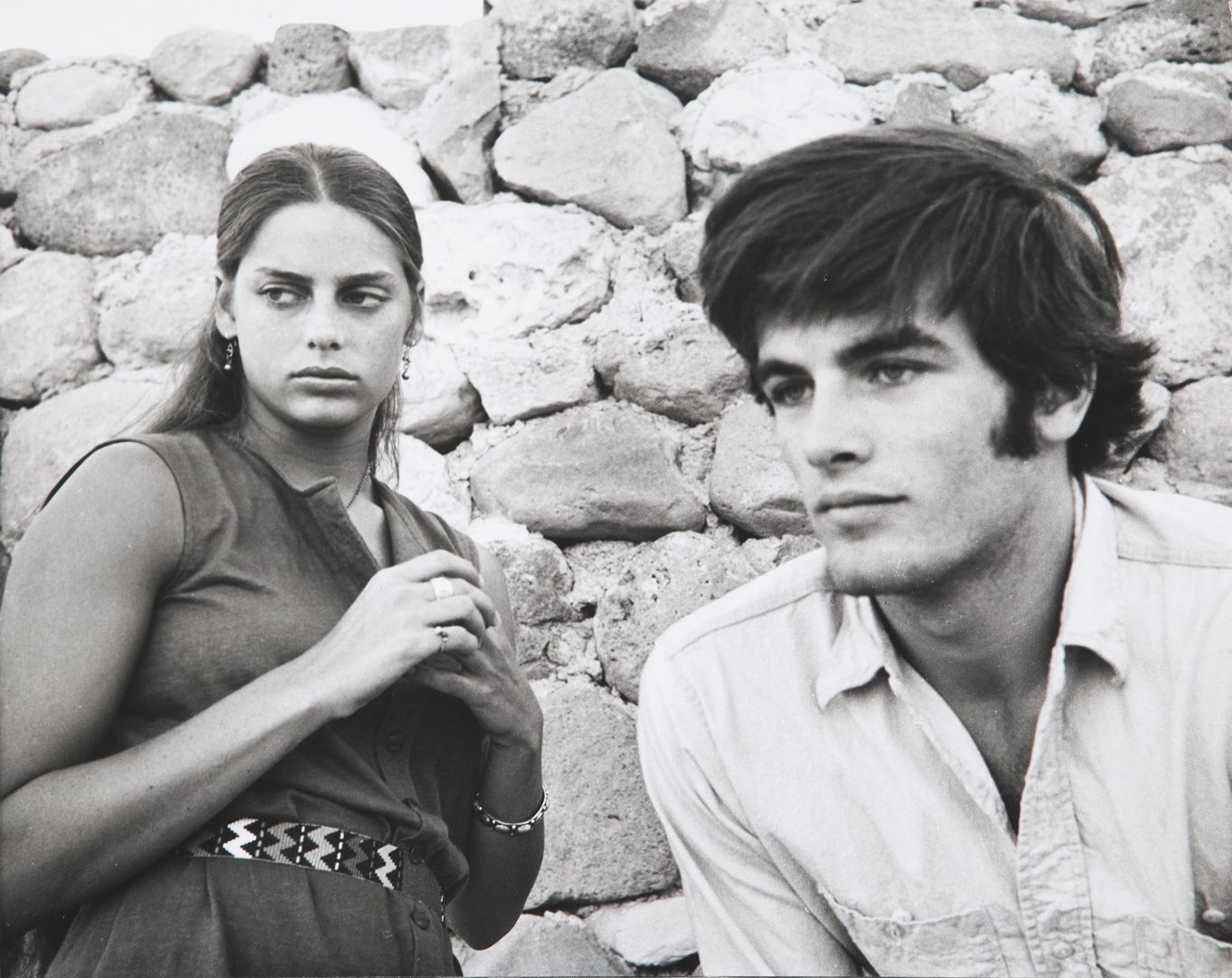

‘Our relationship was purely platonic,’ Mark Frechette says of the director, because Antonioni (politely embarrassed by Mark’s ardor for a ‘spiritual revolution’) never discussed with him the character he was playing, although he spent hours with Daria [Halprin]. Rangers at Death Valley National Monument clashed with hippie members of the Open Theatre during filming of a love-in. College militants didn’t trust Antonioni and suspected he was exploiting them.

So it went. No matter what he did, Antonioni provoked resentment. His maverick methods hark back to the times of I-am-the-boss directors D. W. Griffith and Josef von Sternberg. He is an artist who creates his mystic and original work in absolute control of what he wants, and to hell with busybodies and gossips who don’t understand. Long before this point in his career, he had been bruised by censorship of church and state in Europe. A tense man with a nervous facial tic, Antonioni has become superstitious, suspicious and easily hurt.

Within the shell of his absorption in his work, he is genuinely surprised that some people don’t ‘like’ him. He ‘likes’ Americans and is amused at himself for thinking them a much happier people than he expected. At his return to Rome, he announced that his fellow Italians were unbelievably provincial compared to Americans and were still vainly arguing problems that Americans had resolved 50 years ago.

‘America has changed me,’ he says. ‘I am now a much less private person, more open, prepared to say more. I have even changed my view of sexual love. In my other films, I looked upon sex as a disease of love. I learned here that sex is only a part of love; to be open and understanding of each other, as the girls and boys of today are, is the important part. But it is not fair to ask questions of me before I put my picture together. The responsibility is mine. It is me in front of the camera saying what I feel about my America.'”