In the Breitbart.com post, I mentioned Mark Kostabi’s 1980s high jinks, in which the artist employed a cadre of rotating wage slaves to provide him with ideas and get paint on their hands so he wouldn’t have to. It was vicious commentary on the soulless cash grab of both the art world and Manhattan in that decade, which also allowed the painter a prime place in the gold rush. It was audacious and shameless and disgusting and perfect.

Here’s the opening sharply written 1988 People piece about the artist by Michael Small:

I don’t use people. But I allow them to serve me—Mark Kostabi

A clerk answers the phone in a Manhattan studio and asks painter Mark Kostabi if he wants to take the call. “It’s one of my sleazy customers,” Kostabi cheerily informs a reporter. “He just bought 24 paintings for $122,000 total.” Without informing the customer, Kostabi punches a button to broadcast the conversation over a speaker. “Mark, you’re gonna be a giant in this industry, bigger than a giant!” the caller raves and offers to buy Kostabi dinner. With a Cheshire cat grin, Kostabi accepts, then asks his benefactor, “Are you going to bring wads of cash for me? I hope so.”

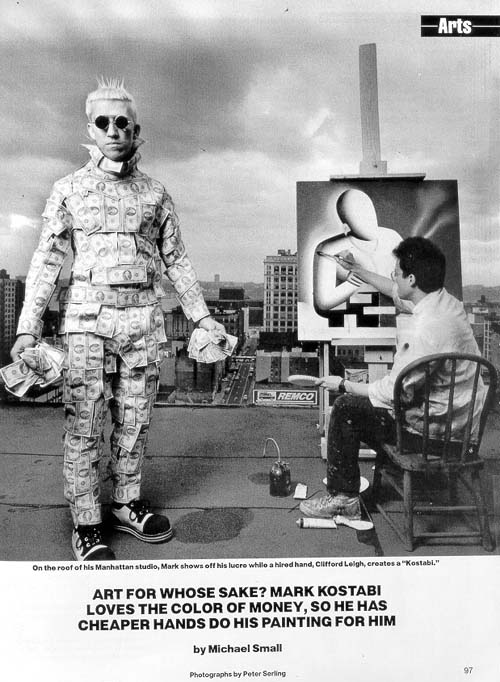

The ’80s deserve Mark Kostabi. In a time when owning certified art has become both a popular investment and a surefire source of power and fame, Kostabi, 27, raises hype to undreamed of levels of crassness. So consumed is he with deals and his image that he has no time left over for painting. Instead he pays other artists $4.50 to $10.50 an hour to imitate the style of his earlier works. His 24-year-old fiancée, a former hairstylist known as Fontaine, earns $300 a week sketching ideas; other hirelings enlarge her drawings on canvas, forge Kostabi’s signature and come up with titles. Two shifts of seven painters produce about six canvases a day, which Kostabi sells for $4,000 to $30,000 apiece. So far in 1988, he has earned more than $1 million.

Clearly he hasn’t done it with flattery. “Anyone who buys my paintings is a total fool,” says Kostabi. “But the more I spit in their faces, the more they beg me to sell them another painting.”

The spat-upon are by no means non-entities. Among the owners of Kostabi’s works, which usually show faceless mannequins armed with such mundane images as cash registers or toilet plungers, are New York’s Guggenheim Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art. His paintings have appeared on a Smith Barney brochure and Bloomingdale’s shopping bags. His new book, Sadness Because the Video Store Was Closed, makes his paintings available to anyone with $19.95. Kostabi says that Sly Stallone paid $20,000 for two of the book’s originals, one showing two women making love. “He went for the T&A paintings,” notes Kostabi.

To say that some people dislike these works is an understatement. “Kostabi’s paintings are so bad that they even subvert the good name of ‘bad painting,’ ” an Artforum reviewer complained in 1986. Not so fast, other experts retort. “Mark has staked out a valid conceptual idea of art, dealing with status and the hypocrisy of the art world,” says Richard Fishman, a Brown University art professor who invited Kostabi to address his classes. Critic Vivien Raynor has praised Kostabis in the New York Times for their “glistening, sometimes morbid, sometimes witty fantasies.”

Kostabi hates to acknowledge any artist as an inspiration, but he admits his mass production schemes are traceable to the Renaissance, when Rubens hired lesser artists to do the details on his paintings. Kostabi’s hunger for publicity, on the other hand, is pure Warhol. “To me, fame is love,” says Kostabi. “And I need love.” But unlike Warhol, who spoke to everyone without revealing anything, Kostabi will answer any personal question. “I don’t mind if you portray me as a totalitarian wretch,” he says. “Whatever it takes to get me on the talk show circuit.”

Though Kostabi’s employees generally find him entertaining, he is not known for his generosity. In 1987 Diana Gentleman, a former model and music student, beat out 75 artists who answered Kostabi’s newspaper ad for someone to supply him with ideas. Less than six months later she stormed out sobbing. “I realized that I was being exploited beyond my imagination,” Gentleman says. “In the first two months I put out 300 drawings, and I wasn’t earning enough to support myself. I found out recently that one of my drawings was turned into a painting that is now in the Guggenheim. He never bothered to tell them that.” Replies Kostabi: “Legally they are my paintings. The artists work on my time, and they’re paid for it.” Well, most of them are. He doesn’t worry about job applicants who send ideas that he uses for nothing.

Among those who do get paid is Claude, 24, who now earns $9 an hour, and has been turning out three to six Kostabis a week for a year. Though his own intricate works are priced at $200 to $2,000, his Kostabis sell for up to $30,000. If that bothers him, he’s not letting on. “It’s a fun job compared to being a waiter,” Claude says. “And I don’t feel that I need recognition. It’s his artistic statement, his name, his reputation.”

Ironically, most of the hip, good-looking painters who now call Kostabi boss are just the sort who would have intimidated him as a nerdy teenager in Whittier, Calif. The third of four children born to Kaljo Kostabi, a maker of brass musical instruments, and his wife, Rita, a fund-raiser, Mark dropped his Estonian first name, Kalev, but otherwise flunked conformity dismally. “I thought I was the ugliest guy in my high school,” he says, “and I was definitely a weirdo. I would stand up on tables in front of the class and scream and spout off.” He studied art for a few years at Fullerton College and at Cal State Fullerton and flunked a business-economics marketing course. “Nobody understood that I could sell things by insulting people, which is what I did for class demonstrations,” he says. “But it worked, and that’s just what I do now.”

Heading to Manhattan in 1982, Kostabi quickly put his chutzpah to work.•