The 1993 version of Hillary Clinton probably would have been far more appreciated in 2016 than this year’s model, but that iteration wasn’t so popular back then. Soon after her husband’s first inauguration, Michael Kelly published “Saint Hillary,” a NYT Magazine article that concerned what Clinton believed was her spiritual mission as the freshly minted First Lady.

Her views seem New Agey in retrospect and were no doubt spurred in part by grief over her father’s death, but Kelly, who was later killed as an Iraq embed, did unwittingly pen the piece at the perfect time to capture the moment prior to the sea change in the culture due to the decentralization of the media, the rise of the Internet and the emergence of Reality TV. It was just before our communications matured and we regressed. Any deep conversation now is just waiting to be trolled. We’re better but we’re worse.

An excerpt:

Driven by the increasingly common view that something is terribly awry with modern life, Mrs. Clinton is searching for not merely programmatic answers but for The Answer. Something in the Meaning of It All line, something that would inform everything from her imminent and all-encompassing health care proposal to ways in which the state might encourage parents not to let their children wander all hours of the night in shopping malls.

When it is suggested that she sounds as though she’s trying to come up with a sort of unified-field theory of life, she says, excitedly, “That’s right, that’s exactly right!”

She is, it develops in the course of two long conversations, looking for a way of looking at looking at the world that would marry conservatism and liberalism, and capitalism and statism, that would tie together practically everything: the way we are, the way we were, the faults of man and the word of God, the end of Communism and the beginning of the third millennium, crime in the streets and on Wall Street, teen-age mothers and foul-mouthed children and frightening drunks in the parks, the cynicism of the press and the corrupting role of television, the breakdown of civility and the loss of community.

The point of all this is not abstract or small. What Mrs. Clinton seems — in all apparent sincerity — to have in mind is leading the way to something on the order of a Reformation: the remaking of the American way of politics, government, indeed life. A lot of people, contemplating such a task, might fall prey to self doubts. Mrs. Clinton does not blink.

“It’s not going to be easy,” she says. “But we can’t get scared away from it because it is an overwhelming task.’

The difficulty is bound to be increased by the awkward fact that a good deal of what Mrs. Clinton sees as wrong right now with the American way of life can be traced, at least in part, to the last great attempt to find The Answer: the liberal experiments in the reshaping of society that were the work of the intellectual elite of . . . Mrs. Clinton’s generation.

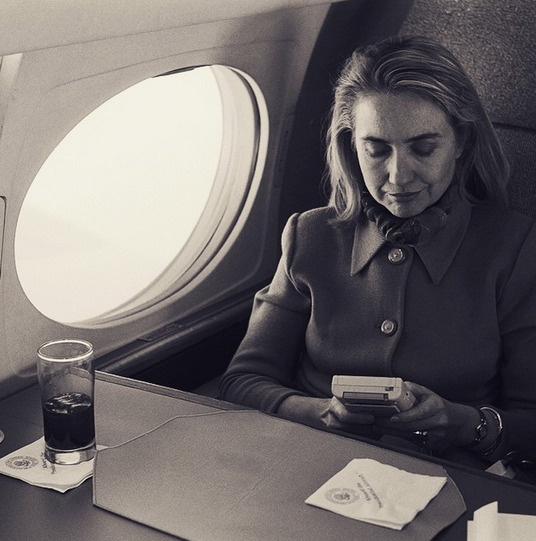

THE CRUSADE OF HILLARY Rodham Clinton began on April 6 in Austin, Tex. There, speaking from notes she had scribbled on the plane, she moved swiftly past the usual thanks and jokes to wade into an extraordinary speech: a passionate, at times slightly incoherent, call for national spiritual renewal.

The Western world, she said, needed to be made anew. America suffered from a “sleeping sickness of the soul,” a “sense that somehow economic growth and prosperity, political democracy and freedom are not enough — that we lack at some core level meaning in our individual lives and meaning collectively, that sense that our lives are part of some greater effort, that we are connected to one another, that community means that we have a place where we belong no matter who we are.”

She spoke of “cities that are filled with hopeless girls with babies and angry boys with guns” as only the most visible signs of a nation crippled by “alienation and despair and hopelessness,” a nation that was in the throes of a “crisis of meaning.”

“What do our governmental institutions mean? What do our lives in today’s world mean?” she asked. “What does it mean in today’s world to pursue not only vocations, to be part of institutions, but to be human?”

These questions, she said, led to the larger question: “Who will lead us out of this spiritual vacuum?” The answer to that was “all of us,” all required “to play our part in redefining what our lives are and what they should be.”

“Let us be willing,” she urged in conclusion, “to remold society by redefining what it means to be a human being in the 20th century, moving into a new millennium.”•