The opening of Caleb Crain’s New York Times Book Review piece about Mathew Brady, Robert Wilson’s portrait of the Civil War-era’s chief portraitist:

“Death was early American photography’s killer app. Since the first pictures required long exposures, it was convenient to have a subject that held still. There was a psychological angle as well. A 19th-century photographer reported that when he visited a town in upstate New York, all the residents welcomed him except the blacksmith, who at first reviled him as a swindler. But then the blacksmith’s son drowned — and the blacksmith came begging for an image of the boy.

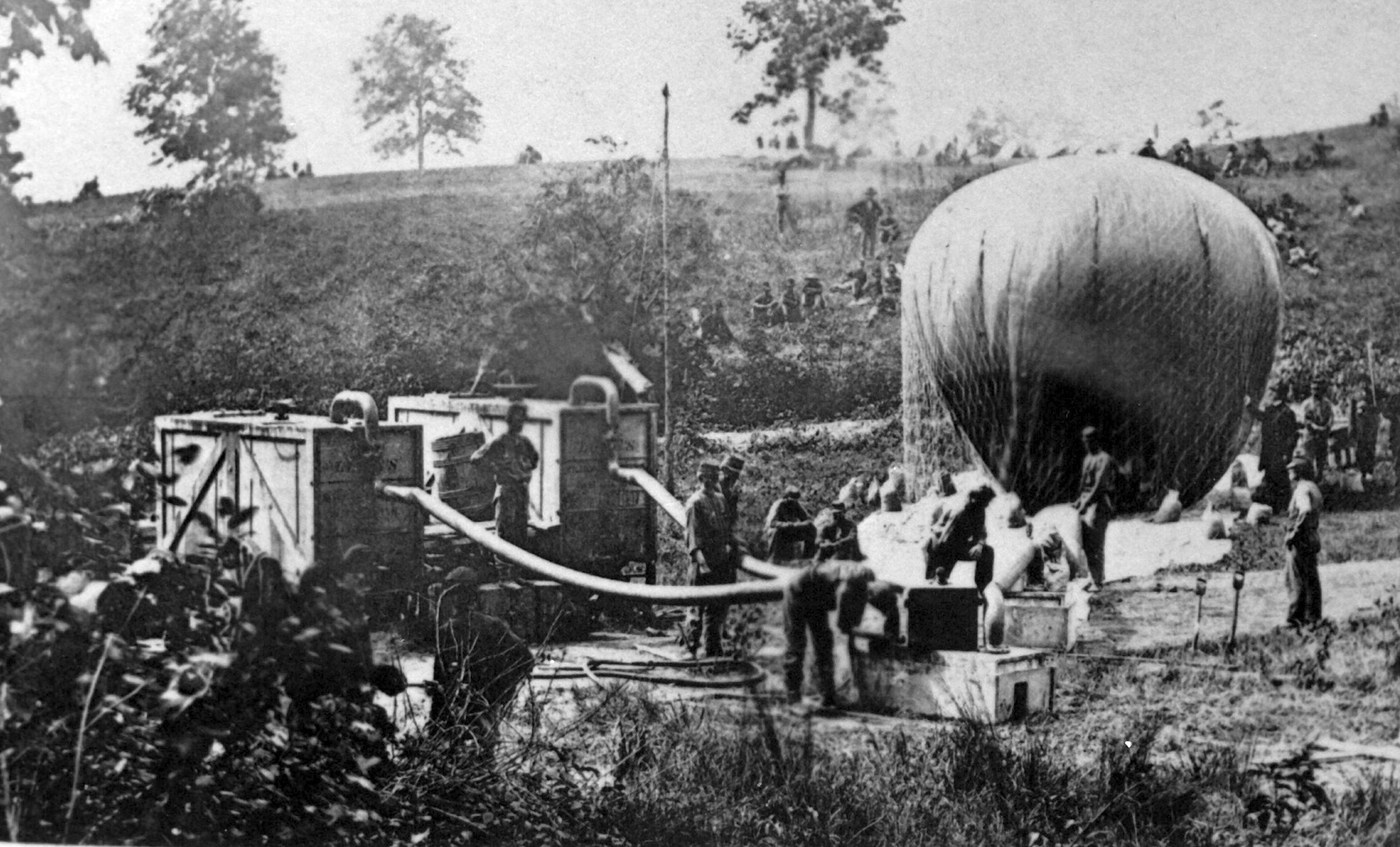

The tale is retold by Robert Wilson, the editor of The American Scholar, in Mathew Brady, his patient and painstaking new biography of the portraitist and Civil War photographer. Brady wasn’t one to overlook a sales tool. ‘You cannot tell how soon it may be too late,’ he warned in an 1856 ad that ran in The New York Daily Tribune, advising readers to come sit for a portrait while they still could. When the Civil War began in 1861, thousands of new soldiers and their families became acutely aware that it might soon be too late. They were willing to pay a dollar apiece for tintypes, and Wilson reports that at Brady’s Washington studio, ‘the wait was sometimes hours long.’

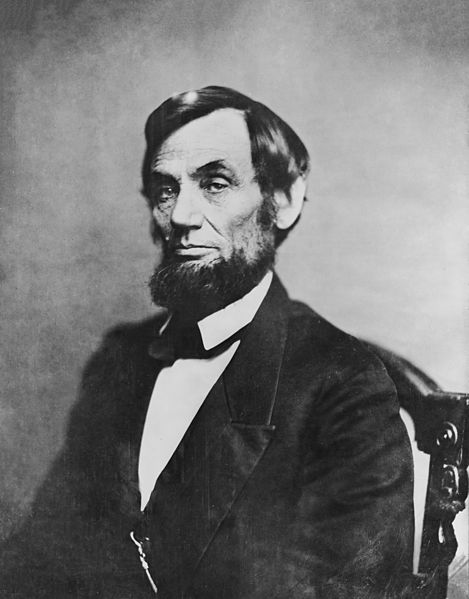

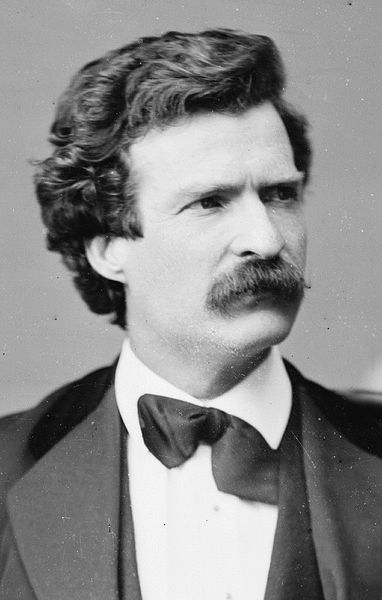

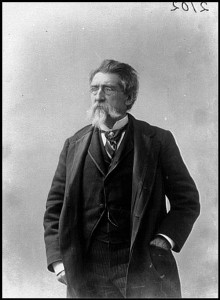

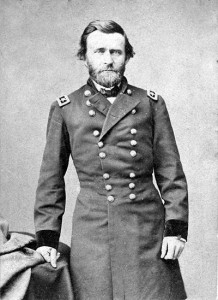

Brady’s other great marketing device was celebrity. His business strategy consisted of photographing politicians, generals and actors for free and displaying their likenesses in a gallery to attract paying customers. His own celebrity was self-made. He was born into an Irish immigrant’s family near Lake George in upstate New York around 1823, and seems to have first entered the photography business in the 1840s as a manufacturer of the leather cases that held the early photographs known as daguerreotypes — fine-grained images developed on copper plates that have an almost holographic quality.”