It’s been clear for some time that Julian Assange is in Vladimir Putin’s pocket, gleefully enabling a nation that murders the political opponents and journalistic critics of the sitting dictator and hacks foreign elections in numerous ways. The Wikileaks founder is an evil man working in the service of an autocracy, not a champion of rights.

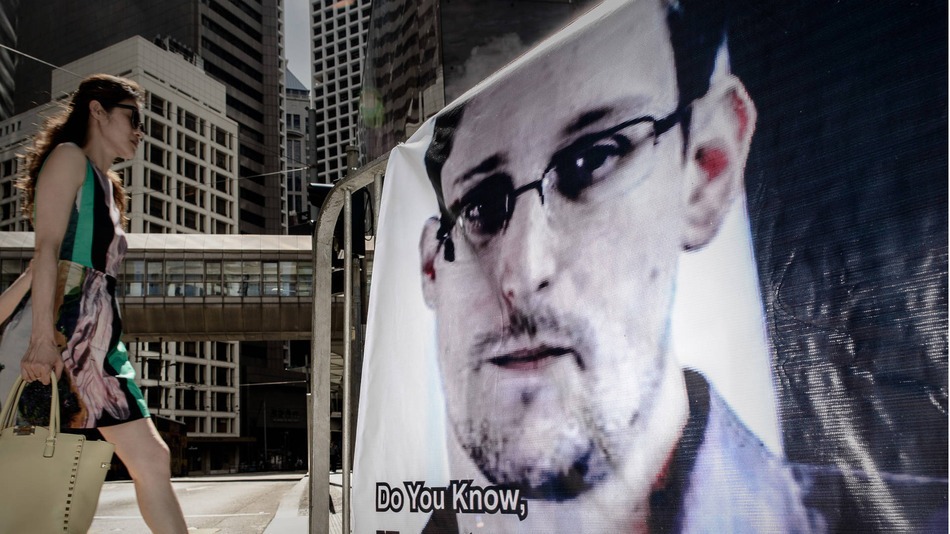

But what of Edward Snowden, whom Assange helped shepherd to Russia after his NSA theft? Is he a righteous whistleblower, as Daniel Ellsberg and Freeman Dyson, among other big thinkers, believe he is? Is he a foolish pawn playing in a game far beyond his capabilities? Is he actually deep into Kremlin espionage? Considering his support for Assange and his equivocations regarding Russia’s nefarious role in the U.S. Presidential election, the latter possibility must at least be pondered.

My initial impression four years ago when Snowden first came to global prominence was that his efforts toward safeguarding privacy, whatever his motivations, were going to meet with failure. These technologies were far beyond taming, were becoming permanent parts of society. Retreat from them was unlikely even if the will was there–and I don’t think it was then or is now.

In 2013, I wrote:

I haven’t really looked at Edward Snowden as hero or villain from the beginning of the NSA leak controversy. Just a cog in a new machine that American media and citizenry can’t seem to fully comprehend–the machine we’re all living in now. Privacy as we knew it–for individuals, corporations and government–has been permanently left in the past. Everybody’s watching everybody, and it will only get easier to spy. And to use one of President Obama’s favorite phrases, this would be a really good time for a teachable moment, for a frank discussion about the way our society is now, how some things have disappeared into the cloud.

But when you take temporary refuge in Russia, as Snowden has, with that country’s brutal and murderous recent history of oppression of journalists and surveillance of its own citizens, you’ve pretty much permanently ceded the moral high ground.•

Snowden still stews in exile in Moscow as Putin’s murderous reign continues, even accelerates, and as our world becomes ever more connected and intrusive. The opening of a Spiegel interview with him conducted by Martin Knobbe and Jörg Schindler:

Spiegel:

Mr. Snowden, four years ago, you appeared in a video from a hotel room in Hong Kong. It was the beginning of the biggest leak of intelligence data in history. Today, we are sitting in a hotel room in Moscow. You are not able to leave Russia because the United States government has issued a warrant for your arrest. Meanwhile, the intelligence services’ global surveillance machine is still running, probably faster than ever. Was it all really worth it?

Edward Snowden:

The answer is yes. Look at what my goals were. I wasn’t trying to change the laws or slow down the machine. Maybe I should have. My critics say that I was not revolutionary enough. But they forget that I am a product of the system. I worked those desks, I know those people and I still have some faith in them, that the services can be reformed

Spiegel:

But those people see you as their biggest enemy today.

Edward Snowden:

My personal battle was not to burn down the NSA or the CIA. I even think they actually do have a useful role in society when they limit themselves to the truly important threats that we face and when they use their least intrusive means. We don’t drop atomic bombs on flies that land on the dinner table. Everybody gets this except intelligence agencies.

Spiegel:

What did you achieve?

Edward Snowden:

Since summer 2013, the public has known what was until then forbidden knowledge. That the U.S. government can get everything out of your Gmail account and they don’t even need a warrant to do it if you are not an American but, say, a German. You are not allowed to discriminate between your citizens and other peoples’ citizens when we are talking about the balance of basic rights. But increasingly more countries, not only the U.S., are doing this. I wanted to give the public a chance to decide where the line should be.•