The Singularitarians’ time frames are largely risible, but attention should be paid to their goals. What they suggest is often only a furthering what we already have. Looking at their predictions for tomorrow can tell us something about today.

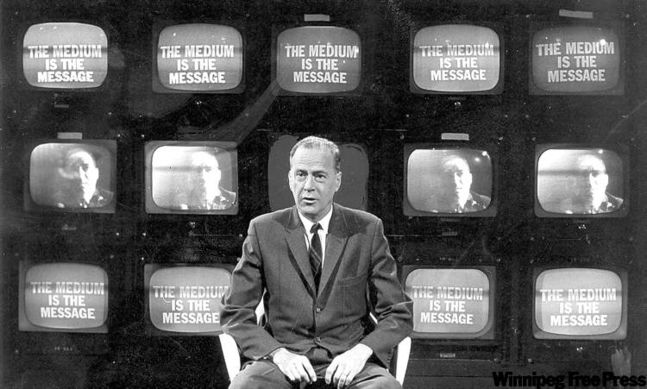

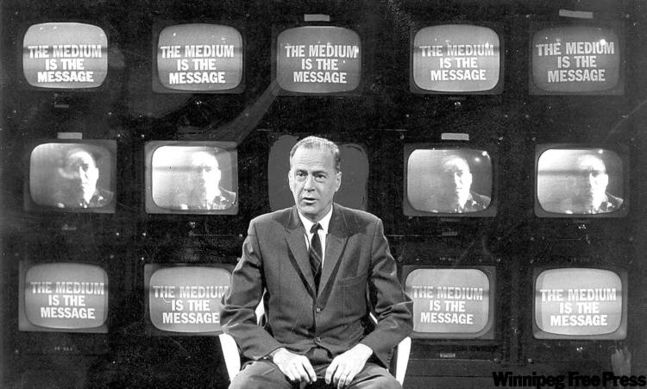

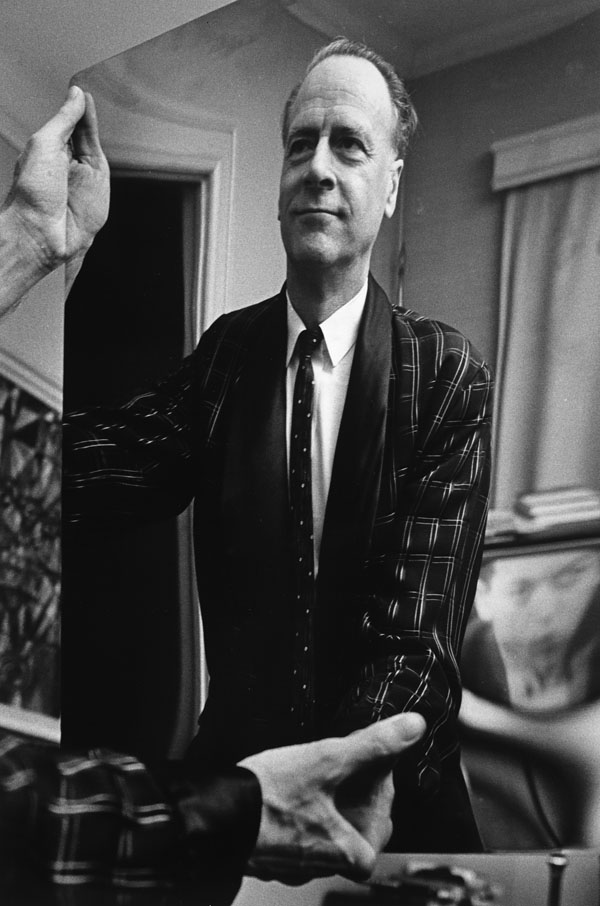

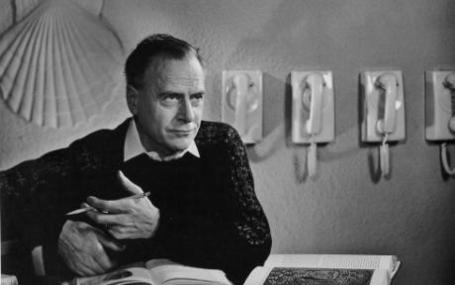

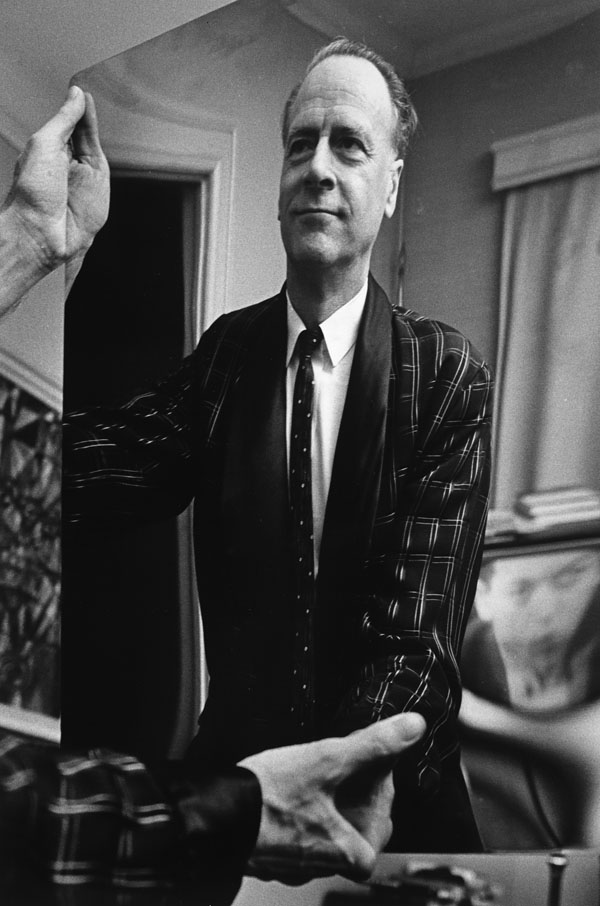

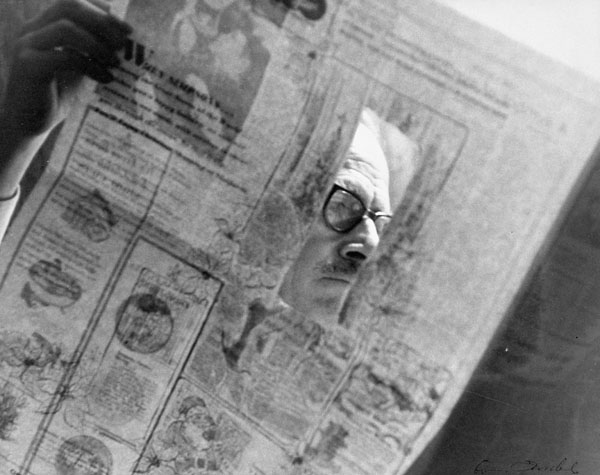

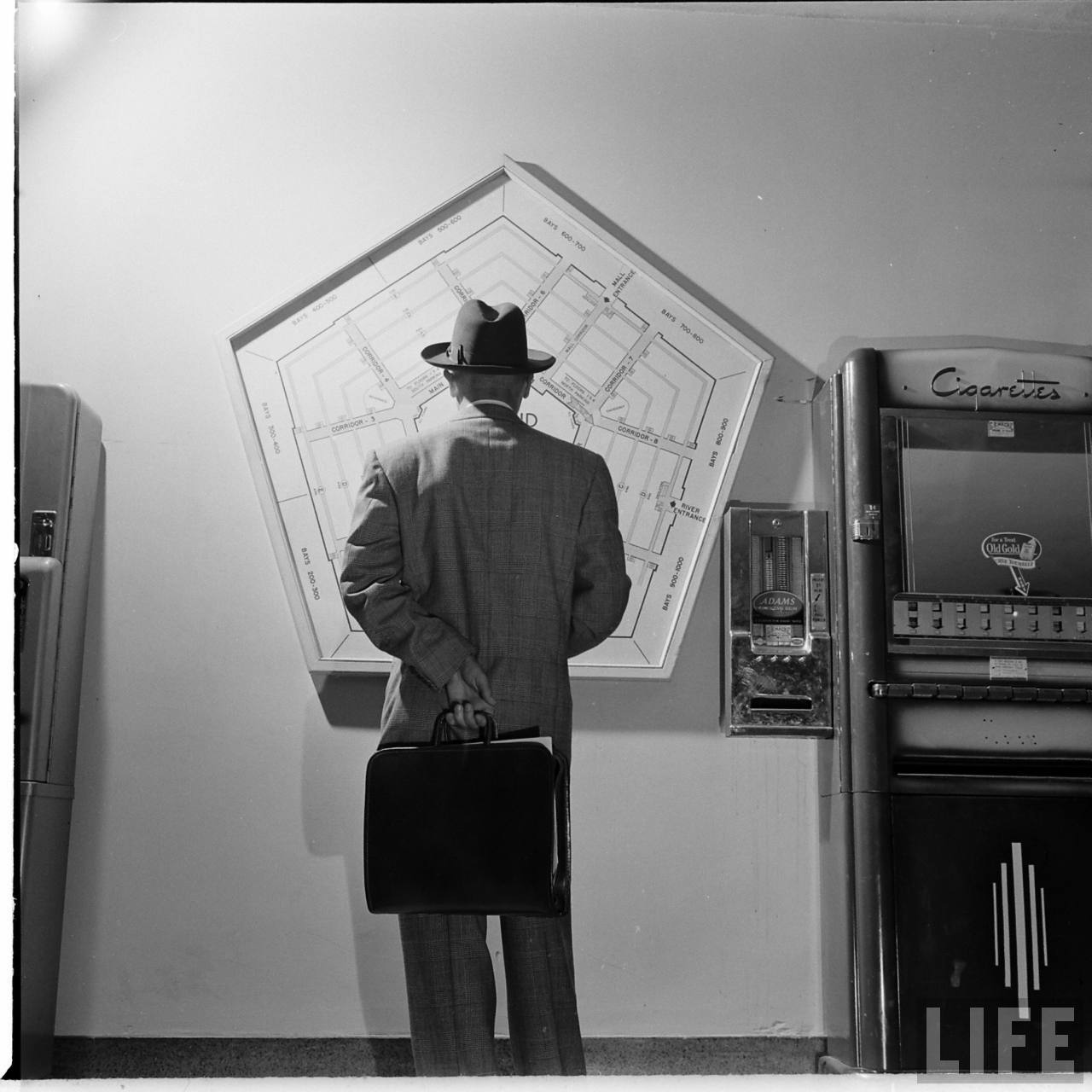

For better or worse, humans are more united by technology than they ever have been before, and for some this is merely prelude. A new Futurism article looks at Peter Diamandis’ dream of “meta-intelligence,” which would require far more radical person-to-person connectedness as well as humans being tethered brain to cloud. His overly ambitious ETA may prove false, but paramount concerns about such an arrangement go far beyond hacking and privacy. Marshall McLuhan dreaded the Global Village he predicted, believing it could be our downfall.

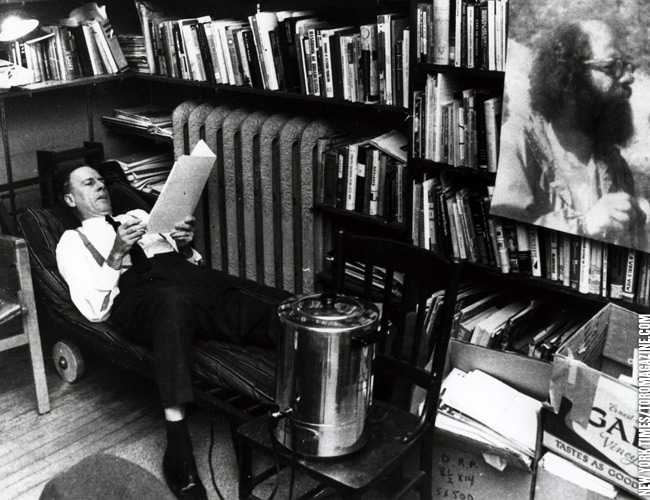

Gary Wolf wrote in Wired in 1996:

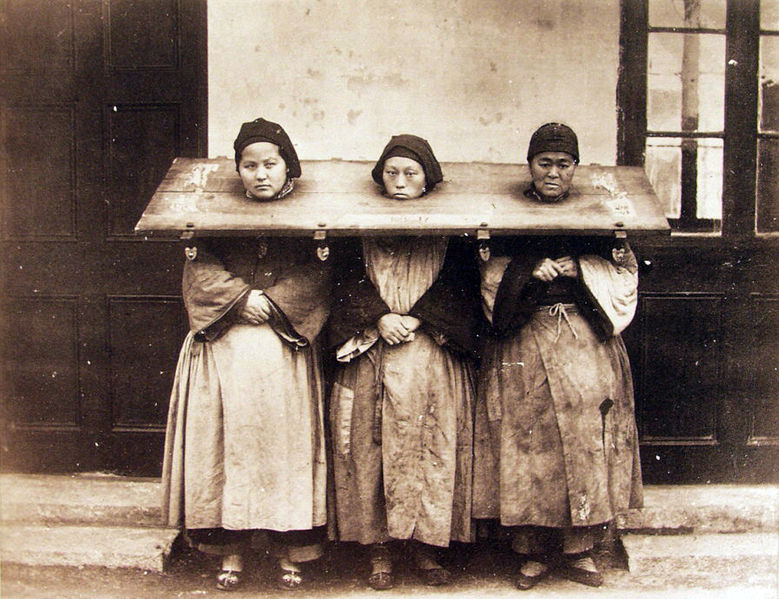

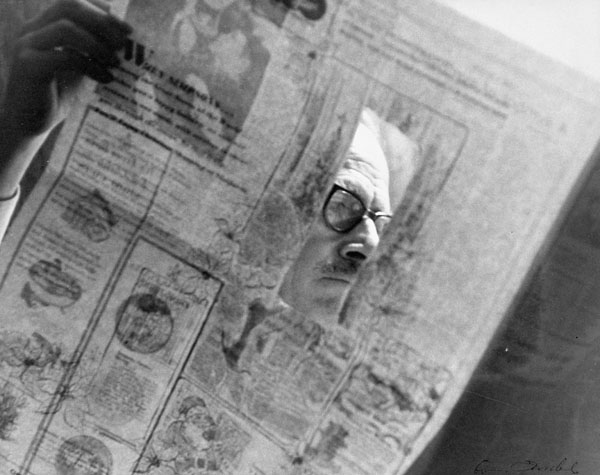

McLuhan did not want to live in the global village. The prospect frightened him. Print culture had produced rational man, in whom vision was the dominant sense. Print man lived in a world that was secular rather than sacred, specialized rather than holistic.

But when information travels at electronic speeds, the linear clarity of the print age is replaced by a feeling of “all-at-onceness.” Everything everywhere happens simultaneously. There is no clear order or sequence. This sudden collapse of space into a single unified field ‘dethrones the visual sense.’ This is what the global village means: we are all within reach of a single voice or the sound of tribal drums. For McLuhan, this future held a profound risk of mass terror and sudden panic.•

Print has certainly been eclipsed, and the Internet and its social media have presented specific outsize problems even a visionary could never have seen coming. These tools can help topple regimes, and all the closeness has allowed those with good or evil intentions to pool their resources and mobilize.

Garry Kasparov is relatively hopeful about what this new normal means for us, but would his arch-nemesis Vladimir Putin have been able to effect the U.S. election without the wires that now run through us all? We have to accept at least the possibility that a highly technological society will be an endlessly chaotic one.

From Futurism:

CHANGE IS COMING

Diamandis outlines the next stages of humanity’s evolution in four steps, each a parallel to his four evolutionary stages of life on Earth. There are four driving forces behind this evolution: our interconnected or wired world, the emergence of brain-computer interface (BCI), the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI), and man reaching for the final frontier of space.

In the next 30 years, humanity will move from the first stage—where we are today—to the fourth stage. From simple humans dependent on one another, humanity will incorporate technology into our bodies to allow for more efficient use of information and energy. This is already happening today.

The third stage is a crucial point.

Enabled with BCI and AI, humans will become massively connected with each other and billions of AIs (computers) via the cloud, analogous to the first multicellular lifeforms 1.5 billion years ago. Such a massive interconnection will lead to the emergence of a new global consciousness, and a new organism I call the Meta-Intelligence.•