One of the things that interests me most about human beings is our tendency to self-delusion, those moments when we take a path so far afield, so confidently that it’s stunning. I don’t mean when we’re basing our decisions on faulty or incomplete information or when there’s a Taleb-ian black swan at play. I mean those times when we should certainly know better but our brains convince us otherwise. I would suggest that maybe it’s an evolutionary survival mechanism, except that such behavior can get us killed. And we all possess this ability to be block out the truth. We are wrong though we think we are right.

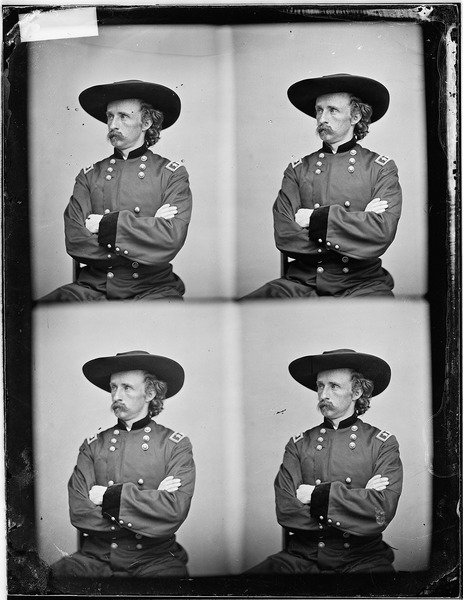

George Armstrong Custer, for instance, knew he was correct. From “It Was Only 75 Years Ago,” Life magazine’s 1951 retrospective of the Battle of the Little Bighorn:

“He pressed forward although his men were weary and his supply train far behind.

Even when, on the morning of June 25, his force sighted a huge smoke haze on the other side of the Little Bighorn, indicating an enormous Indian camp, Custer disregarded warnings of his officers and scouts that a great mass of enemy was near. (It was, in fact, the biggest Indian mobilization in U.S. history.)

Inexplicably Custer divided his small force into three. He sent 120 men under Captain Frederick Benteen on patrol of the south. He then ordered Major Marcus Reno and 112 men to move toward what he still stubbornly believed was only 1,500 Sioux. Benteen encountered nothing. Reno ran into several thousand Sioux, made a desperate stand, then retreated with hideous losses to the other side of the river. There, joined by Benteen, he was able to re-form. Custer, to the perennial mystification of historians, never came to Reno’s support but, after trying to cross the river, proceeded north. He sent back a last message: ‘Benteen: Come on. Big Village. Be quick. Bring packs.’

Knowledge of what happened after that exists only in the misty minds of a few old Indians. Some 20 miles from where he separated his command, Custer and his 225 men were overwhelmed by almost 6,000 vengeful Sioux. From battlefield evidence they attacked from the southwest, drove the cavalrymen up a little mound and there killed them, including Mark Kellogg, a Bismarck, N. Dak. Tribune correspondent whom Custer brought along (against orders) to chronicle his new triumph and whose dispatches were later found in his pouch. Some of the dead were horribly mutilated; most were stripped. But George Custer, shot through the temple, was found with a peaceful expression on his face. He looked like a man who, hungry for glory all his life, had finally found it.”