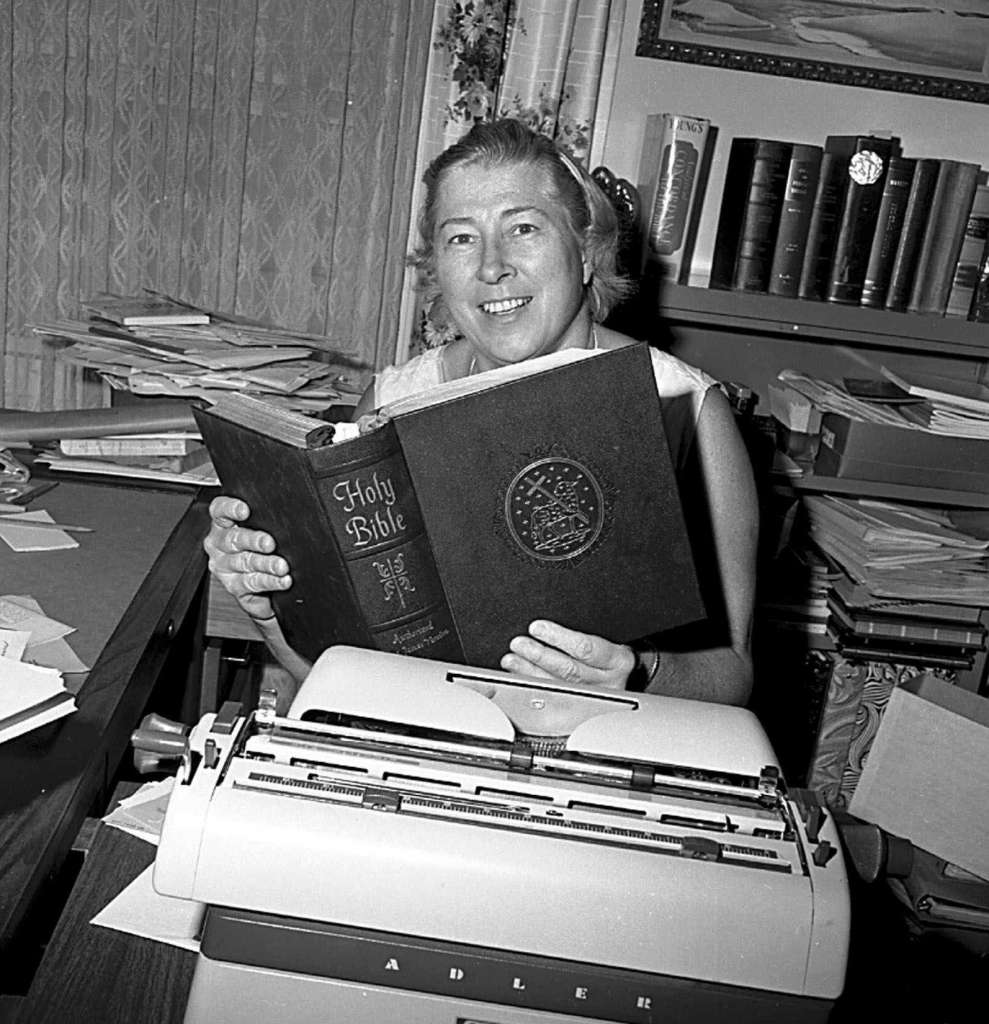

In 1989, six years before her murder, Madalyn Murray O’Hair, the Carrie Nation of holy water, was profiled by Lawrence Wright, then of Texas Monthly. The outrageously quotable, oft-jailed atheist activist was no doubt a welcome assignment for a budding journalistic talent like Wright, who visited her Austin offices a quarter century after her strident efforts had removed compulsory prayer from American public schools.

In the twilight of the Reagan years, O’Hair thought the country was headed toward a Neo-fascism enabled by a confluence of plutocracy, technology and religion. In retrospect, not a bad prediction.

An excerpt from the Texas Monthly piece is followed by some other articles and videos about her.

From Wright:

As with most Americans my age, my life already had been given a good shaking by Madalyn Murray O’Hair. For the first ten years of my schooling, I listened to prayers and Scripture every morning following the announcements on the P.A. system. I don’t recall ever questioning the propriety of such action or wondering what my Jewish classmates, for instance, might think about hearing Christian prayers in public school. But in the fateful fall of 1963 we began classes amid the enormous hubbub that followed the Supreme Court decision. The absence of morning prayers was widely seen as a prelude to the fall of the West. And the woman who had toppled civilization as we knew it was some loudmouthed Baltimore housewife—that was my impression—who then proceeded to wage another legal campaign to tax church property. She was the first person I had ever heard called a heretic. She jumped out of the front pages with one outrageous statement after another; indeed, the era of dissent in the sixties really began with Madalyn Murray, who styled herself as the “most hated woman in America.”

Certainly she was the most provocative. Soon after the school-prayer decision, Mrs. Murray, as she called herself then, was charged with assaulting 10 Baltimore policemen (she has inflated the number of policemen to 14, then 22, and then 26). She fled first to Hawaii, where she took refuge in a Unitarian church. Then she went to Mexico, which summarily deported her to Texas in 1965. Her odyssey ended in Austin, where she successfully fought extradition to Maryland, married an ex-FBI informer named Richard O’Hair, and remained long after the Maryland charges were dropped.

Over the years I followed Madalyn O’Hair in the way one keeps tabs on celebrities, as she bantered with Johnny Carson, sued the pope, or burst into a church and turned over bingo tables. When I was in college, she came to speak. By then she had achieved a kind of sainthood status with the undergraduate intelligentsia. True to her billing, she raked over capitalism and Christianity and especially Catholicism, unsettling if not actually insulting every person in the auditorium. Afterward she repaired to the student center and held forth in the lobby, giving an explicit and highly titillating seminar on the variations of sexual intercourse. I had never seen anyone with such a breathtaking willingness to endure public hatred. “I love a good fight,” she boasted to the press. “I guess fighting God and God’s spokesmen is sort of the ultimate, isn’t it?”

Neutrality is never present around Madalyn O’Hair; she polarizes everyone. …

“I do think we’re in a steady retreat. There’s an absolute steady retreat into what I call a neofascism—but it’s really old-time fascism—into a robber-baron society and a religiously dominated society, and that’s not cyclical, because they have new weapons at hand now, mainly communications technology with which they can rapidly disperse ideas…”•

The atheist crusader was right that children should not be forced to pray in public school, but that doesn’t mean she was an ideal parent. O’Hair had dissent in her family that she would not brook: Her eldest son, William, became a religious and social conservative in 1980. His mother, showing characteristic outrage, labeled him a “postnatal abortion” and cut off all communication. From a 1980 People article about the familial rift:

He traces her atheism to that self-absorption and hubris and to an aggressive antiestablishment streak that led her (with her two sons) into a variety of left-wing causes—even, he claims, to the Soviet embassy in Paris in search of exile. Rejected by Moscow, she retreated angrily back home to Baltimore where, as he puts it, “The rebel found a cause in prayer at school.”

As the pawn of her crusade, Bill was excoriated by fellow students, given extra homework by his teachers and baited into schoolyard fights; once, he remembers, some classmates tried to push him in front of a bus. “While Madalyn was busy with her rhetoric, newsletters, fund raising and publicity,” he says, “I was fighting for my life.” At 17, Murray ran afoul of the law. He eloped with a girl despite an injunction won by her parents that prohibited him from seeing her. Police intervened, and both Bill and his mother were charged with assaulting them. (The young woman left Bill and their infant daughter two years later.)

Throughout Bill’s life his mother’s reputation has been a millstone. Drafted a year after his marriage broke up, he was subjected to grueling Army interrogation about Madalyn’s activist causes—and asked to sign a statement repudiating her left-wing politics (he did). After discharge he took a series of jobs in airline management and remembers living in fear that his employers would find out who his mother was and fire him. He complains she even threatened to expose him herself when he balked at giving her discounted airplane tickets that were due him as an employee.

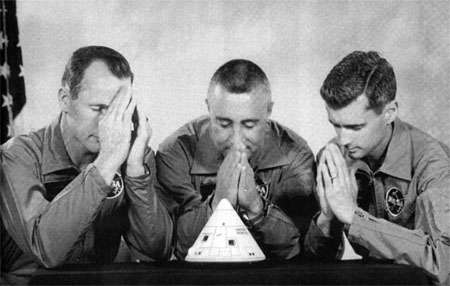

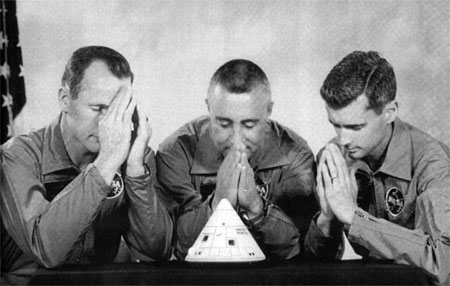

In 1969 he asked Madalyn for his daughter, whom she had kept while he was in the Army. She refused, they fought a custody suit and Madalyn won. Still, in 1974, when her second husband was ailing and the AAC foundering, Bill agreed to come to Austin and help out. He did so with great success—and increasing doubts. He multiplied the AAC’s annual income, which underwrote a flurry of new lawsuits—over church tax exemptions, the words “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance and ‘In God We Trust’ on coins. But Bill says he began to wonder: “Why couldn’t we buy a new X-ray machine for a hospital? Why did we have to buy a new Cadillac and mobile home for Madalyn, or sue somebody to prevent prayer in outer space? I started to think it was because my mother was basically negative and destructive.’ He began to drink too much—”diving into the bottle to forget,” as he describes it. Six months after he came to Austin, Madalyn turned her animus on him once too often. “I told her to get f——-,” he recalls, ‘and got the hell out.”

By that time Bill was an alcoholic. He had a new marriage and a new job as an airline management consultant, but felt his life was falling apart.”•

From the 1965 Playboy interview with the “most hated woman in America”:

Playboy:

What led you to become an atheist?

Madalyn Murray O’Hair:

Well, it started when I was very young. People attain the age of intellectual discretion at different times in their lives — sometimes a little early and sometimes a little late. I was about 12 or 13 years old when I reached this period. It was then that I was introduced to the Bible. We were living in Akron and I wasn’t able to get to the library, so I had two things to read at home: a dictionary and a Bible. Well, I picked up the Bible and read it from cover to cover one weekend — just as if it were a novel — very rapidly, and I’ve never gotten over the shock of it. The miracles, the inconsistencies, the improbabilities, the impossibilities, the wretched history, the sordid sex, the sadism in it — the whole thing shocked me profoundly. I remember l looked in the kitchen at my mother and father and I thought: Can they really believe in all that? Of course, this was a superficial survey by a very young girl, but it left a traumatic impression. Later, when I started going to church, my first memories are of the minister getting up and accusing us of being full of sin, though he didn’t say why; then they would pass the collection plate, and I got it in my mind that this had to do with purification of the soul, that we were being invited to buy expiation from our sins. So I gave it all up. It was too nonsensical.•

A 30-minute documentary about O’Hair, and a 1970 Donahue episode in which she debated Rev. Bob Harrington (voice and picture not properly synced.)