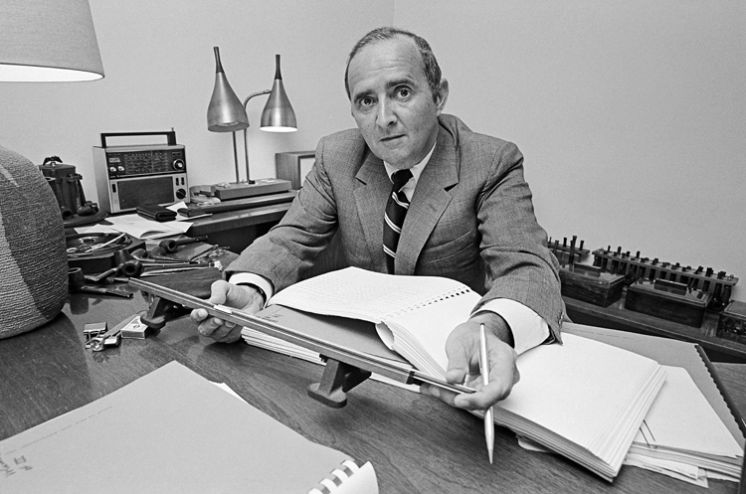

Louis Harris, the most famous American pollster of the twentieth century, just died at 95. I worked for the company in its last pre-acquisition days when I was an undergraduate. The offices were located at 630 Fifth Avenue, a building with a giant Atlas statue at its entrance. On a lunch break one day, I sat across the street on the steps of St. Patrick’s Cathedral reading a copy of The Stories of John Cheever. I absorbed “The Country Husband” (still my favorite tale by the writer), which coincidentally mentions the very same Atlas building right before my eyes. Cool.

What I can recall about the experience:

- The break room had a shrine to the late professional wrestler Bruiser Brody, who had been murdered in 1988 in a backstage altercation Puerto Rico. There’s even a Mountain Goats song about the stabbing.

- The Harris Poll was the least buttoned-down workplace I’ve ever come across. The crew was a mix of anarchist squatters from the Lower East Side (who apparently had no regular access to soap), a few college students like myself, a handful of aspiring actresses and theater directors, several little people, and some LGBTQ folks who told me they had trouble getting non-phone work because they couldn’t or wouldn’t masquerade as something that was more acceptable in America at the time. Oh, and there was a very nice and quiet middle-aged woman who was said to be a former Bob Fosse dancer who’d fallen on hard times.

- The employees were almost universally extremely liberal politically, even radical, though that seemed to have no influence over survey outcomes. Many polls wound up reflecting a strong conservative opinion.

- I was instructed that when conducting phone surveys I needed to be more assertive with women in the Midwest, since they could be bossed around. It wasn’t exactly in those words, but close. I was told precisely that when Middle American females told me they weren’t interested in doing a survey that I was to ask to speak to the “man of the house.”

- I once referred to the company as “Lou” Harris and was immediately told to never, ever do that again. The founder had retired by then but was still a sort of spectral presence.

From Robert D. McFadden’s New York Times obituary of the man who called too much:

He preferred to be called a public-opinion analyst rather than a pollster, a word that he believed trivialized what he did, which went beyond gathering data into new realms of interpretation — useful to clients of his consulting firm and more meaningful to millions who watched his analyses on the CBS and ABC television networks or who read his nationally syndicated newspaper and magazine columns.

His results were sometimes wrong. And critics questioned his early practice of using his polls to promote candidates — notably John F. Kennedy in his 1960 presidential race — for whom he worked as a campaign strategist. But he gave up political advocacy after a few years to concentrate on public polling and analyses for the newspaper and television jobs that made him a household name in America.

In the 1960s, he developed television’s ability to project national election winners on the basis of early returns after polls closed in the East. But critics said projections before the polls closed in the West discouraged some voters from casting ballots, and the networks voluntarily ended the practice.

Mr. Harris denied that his work affected the outcome of elections or corrupted voting processes. He rejected charges that he was too commercial, although he made a fortune in market research. And he scoffed at accusations that his polls reflected a liberal Democratic bias; he said he often worked for Republicans and was guided by principles of fairness and accuracy.

Like Elmo Roper and George Gallup, his pioneering predecessors, Mr. Harris plumbed attitudes with face-to-face interviews, using carefully worded questions put by trained interviewers to subjects selected as part of a group that was chosen as demographically representative of the nation. (Telephone interviews, faster and less expensive, came into wide use in the late 1970s, and proved to be just as valid.)•