If you want to argue the best articles from another era of the New Yorker are better than the best of the current iteration, I suppose you could, but I don’t think the journalism has ever been so consistently on top as in the modern version.

Even by those usual high standards, 2015 has already been an exceptionally rich year. Consider just last month. I don’t think there’s been a day since reading Patrick Radden Keefe’s IRA revisitation, “Where the Bodies Are Buried,” that his complex piece hasn’t popped into my mind.

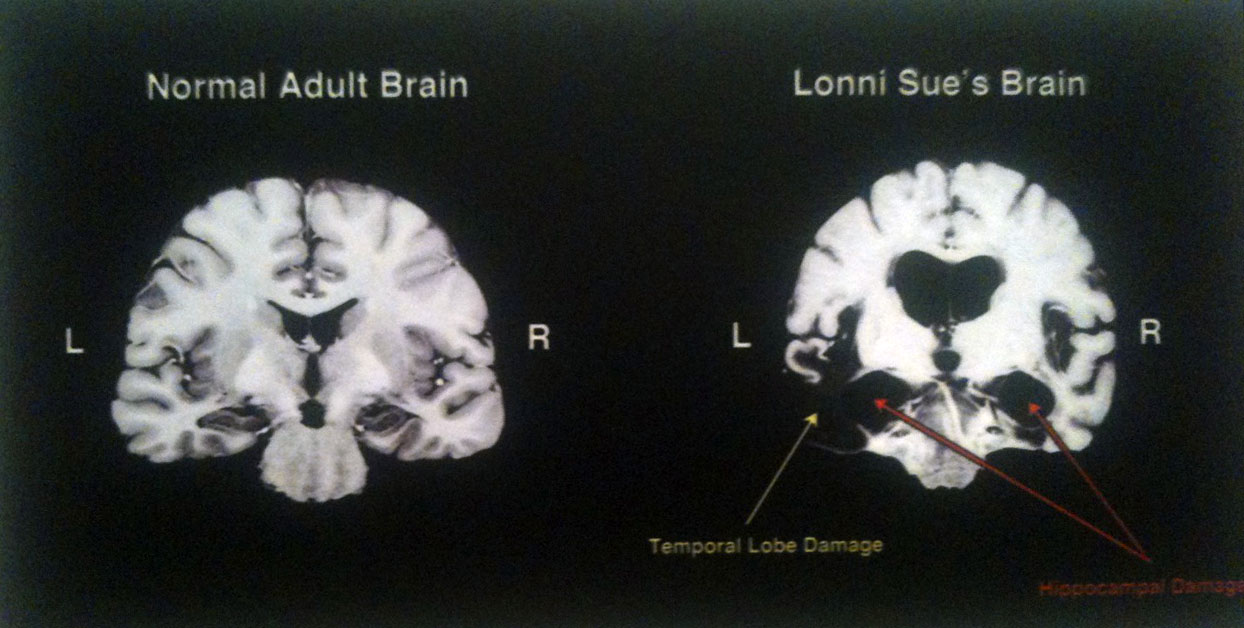

Another example: Daniel Zalewski’s “Life Lines,” which profiles artist Lonni Sue Johnson, whose hippocampus was left in ruins by encephalitis. The article is filled with spare, knowing phrases like this one: “Johnson’s reliance on the tote bag is a radical extension of what humans naturally do.” Dedicated study of the remaining functions of Johnson’s damaged brain may tell us a lot about our own intact ones. An excerpt:

Memories can be both a pleasure and a hardship. The most dissatisfied people, Kierkegaard observed, can “be found among the unhappy rememberers.” As [Nicholas] Turk-Browne put it, “Memory is such a great thing, but it’s also where your anxiety comes from.” Johnson’s emotional load certainly seems lighter: she is never going to regret making an impatient remark to Aline or worry for days that the Princeton researchers find her tedious. But even the sketchiest memories can weigh someone down. Johnson knows how deeply she loved her past, even if she can perceive only some of its outlines. Aline said, “I took a walk with her the other day, and an airplane flew over and she said, ‘Do you know what that makes me think of? Do you know how much I miss flying?’ And she just went on and on, and got so caught up in that. We were walking on one of the most beautiful days outside that there could be, and she could hardly see the beauty, because she was so caught in the past.”

Aline asked her sister what she’d seen in the scanner.

Silence. “All sorts of things.”

Aline pressed. Had she been sitting up or lying down?

“Lying down—wasn’t that true?”

Aline looked at Turk-Browne searchingly. Correct answers made it seem as if Johnson’s temporal window were expanding. Diplomatically, Turk-Browne observed that Johnson’s answers could reflect semantic knowledge—a general sense of what happened inside the scanner. “It’s amazing how much you can get by on semantic memory,” he told me later.

Johnson and I had said hello earlier that morning. Though I repeatedly mentioned that I was a journalist, she seemed to consider me one of the ambient scientists in her life. “You look so familiar,” she said, and complimented the plaid shirt that I was wearing: “It’d make a great puzzle.”

The data from a dozen scanning sessions took months to assess, and in November Jiye Kim presented the results at a gathering of the Society for Neuroscience, in Washington, D.C. Johnson’s brain had retained objects and scenes for three minutes—as long as intact brains did. To Turk-Browne, the results proved, surprisingly, that “repetition suppression is a form of short-term memory that does not require the hippocampus.” He theorized that another—as yet undiscovered—“visual buffer of recent experience” must be “propping up the visual system and feeding into it.” Perhaps the visual cortex had its own scratch pad. Johnson’s unique brain had exposed a mystery inside everyone’s brain.

As Johnson was leaving the laboratory that day, Turk-Browne asked, “So, where are we?” Her eyes darted. “We’re in . . . a wonderful place,” she said, smiling uneasily.•