We can’t really clone a mammoth (like George Church wants to) or passenger pigeon (as Stewart Brand hopes to) because we don’t have living tissue from these creatures, so we would have to employ gene editing to approximate them. The question is why, what’s the purpose? Lindsay Abrams of Salon speaks to this issue in an interview with Beth Shapiro, author of How to Clone a Mammoth. An excerpt:

Question:

So the big question that’s running through my mind — and I know there are different answers to this — is just, why? Why devote the resources to trying to bring things back from extinction?

Beth Shapiro:

Those are two very different questions. I’ll first start with the first one. I think that it’s really important in any one of these cases to start off thinking about this process — even before we get into really trying to figure out what the technical, ethical and ecological challenges of any particular de-extinction might be — by having some compelling reason to do it. I think that is absolutely critical.

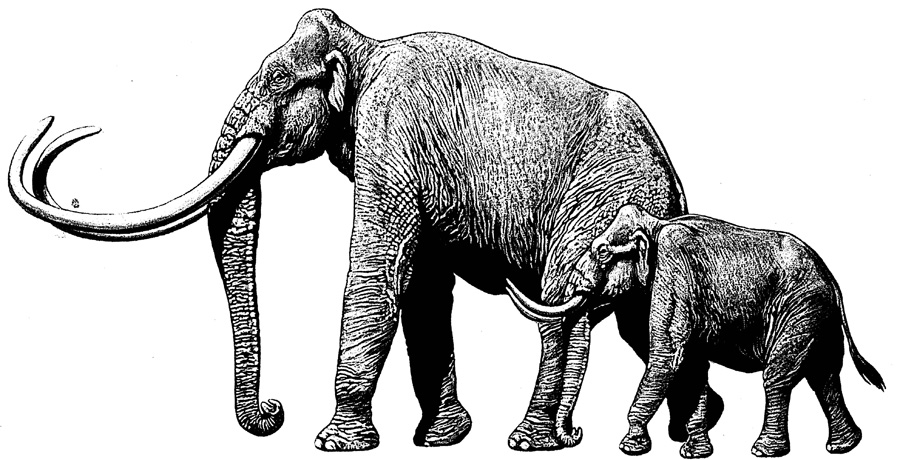

For the mammoth, if we skip over technical, ethical, ecological problems right now, the answer to the question of why we might want mammoth-like traits back I think is possibly one that’s pretty easy to answer. For example, many of us don’t really want to contemplate a world without elephants, but even elephants are endangered and their habitat is disappearing and they’re being poached and it’s very hard to protect them. The IUCN lists them as an endangered species right now. What if we could use this genome editing technology to make elephants that had a little bit of mammoth-like traits, just enough to allow them to live in colder climates like Europe and North America, maybe even Siberia and Alaska, these high Arctic climates? Could we use this technology as a way to save elephants? I think that is a potentially compelling reason to do this research.

Another reason why that’s been tossed around a bit comes from Sergey Zimov, with the Russian Academy of Sciences, who works up in Cherskii, in northeastern Siberia. He has this place called Pleistocene Park, where he has bison and horses and a bunch of different species of deer. He’s shown that just having these herbivores on the landscape, walking around and turning the soil and recycling nutrients and distributing seeds, has been enough to reestablish this rich resource for herbivores there — this dense grassland that lives there and allows these animals to flourish. He’s shown that other species like saiga antelopes, that are also endangered, have come to the park now because it’s a great place for them to come and find stuff to eat. So what if having this big herbivore back on the landscape was actually better able to do that, to recreate this rich resource for other species to use, and in a way could be used as a way to conserve biodiversity in the present day? Again, not just elephants, but these other species that lack habitat.

So compelling reasons to consider bringing extinct species or traits back to life are things like that, not to study mammoths. If we were to bring some animal back that was a hybrid between an elephant and a mammoth — and it necessarily would be — this would not be a good way to study mammoths. It wouldn’t be a mammoth, so we wouldn’t learn anything from that. But, to save elephants and reestablish these ecosystems, those are compelling reasons.•