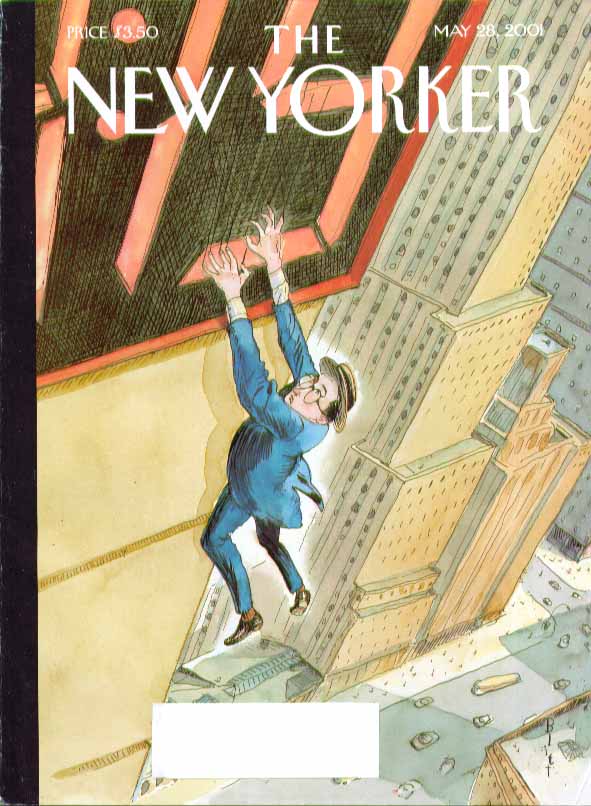

From a 1948 New Yorker piece by Lillian Ross about young Norman Mailer, who was experiencing his first rush of fame with The Naked and the Dead:

“Mailer’s royalties will net him around thirty thousand this year, after taxes, and he plans to bank most of it. He finds apartments depressing and has a suspicion of possessions, so he and his wife live in a thirty-dollar-a-month furnished room in Brooklyn Heights. He figures that his thirty thousand will last at least five years, giving him plenty of time in which to write another book. He was born in Long Branch, New Jersey, but his family moved to Brooklyn when he was one, and that has since been his home. He attended P.S. 161 and Boys High, and entered Harvard at sixteen, intending to study aeronautical engineering. He took only one course in engineering, however, and spent most of his time reading or in bull sessions. In his sophomore year, he won first prize in Story’s college contest with a story entitled ‘The Greatest Thing in the World.’ ‘About a bum,’ he told us. ‘In the beginning, there’s a whole tzimes about how he’s very hungry and all he’s eating is ketchup. It will probably make a wonderful movie someday.’ In the Army, Mailer served as a surveyor in the field artillery, an Intelligence clerk in the cavalry, a wireman in a communications platoon, a cook, and a baker, and volunteered, successfully, for action with a reconnaissance platoon on Luzon. He started writing The Naked and the Dead in the summer of 1946, in a cottage outside Provincetown, and took sixteen months to finish it. ‘I’m slowing down,’ he said. ‘When I was eighteen, I wrote a novel in two or three months. At twenty-one, I wrote another novel, in seven months. Neither of them ever got published.’ After turning in the manuscript of The Naked and the Dead, he and his wife went off to Paris. ‘It was wonderful there,’ he said. ‘In Paris, you can just lay down your load and look out at the gray sky. Back here, the crowd is always yelling. It’s like a Roman arena. You have a headache, and you scurry around like a rat, like a character in a Kafka nightmare, eating scallops with last year’s grease on them.'”