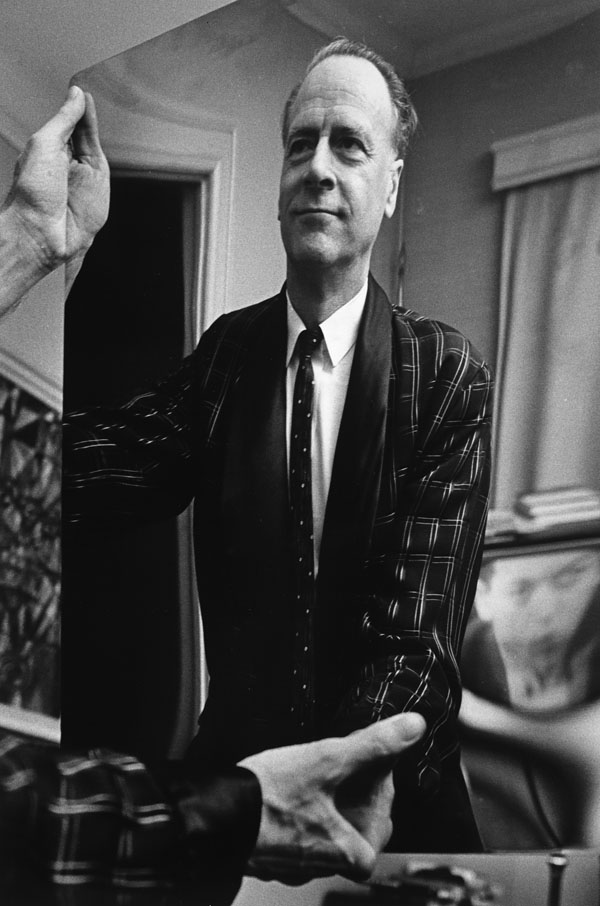

For much of the 1960s, Lewis Lapham was a Saturday Evening Post correspondent who had the entire world as his beat, covering of-the-moment stories like the Beatles’ ill-fated 1968 visit to the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Two years after that fascinating debacle, Lapham was in Alaska, now for Harper’s, to file a report about the black-gold rush, as oil money was remaking the frontier state, for better or worse. The opening of “Alaska: Politicians and Natives, Money and Oil“:

“Sunday evening, January 18, 1970. I arrived in Juneau yesterday afternoon, and already I’ve met twenty-seven people with twenty-seven contradictory visions of paradise regained. The confusion begins with the money.

Last September, at an auction in Anchorage, the state of Alaska raffled off oil concessions on the Arctic Ocean for $900 million. Which, in Alaska, is more money than princes find in fairy tales. Although two and one-half times the size of Texas, the state has a population of 280,000 (equivalent to the population of Des Moines, Iowa). For years the state has been poorer than Appalachia, dependent on federal grants to rescue it from annual bankruptcy; now that it is rich nobody knows how to distribute the largess.

I envy none of the politicians convened in this shambling, wooden town for the present meeting of the State Legislature. Almost all of them must stand for election later in the year (not only the Governor but also the entire Senate and half the House), and the more ambitious among them no doubt look upon the money with the gratitude of a crowd of Eskimos gathered around the body of a beached whale. I suspect, however, that the majority, more timid and mindful of the extravagant public expectations, will prefer to do nothing.

That is too bad only because they have a chance to do so much. In many ways Alaska resembles the American frontier one hundred years ago; like California before the freeways or Lake Erie before the fish died. Conceivably, the Alaskans could learn from the mistakes so evident elsewhere in the landscape; conceivably, they could come up with an alternative to the habit of mind (much admired by local chambers of commerce) that plunders the available resources and divides the spoils among the surviving interests. In the beginning there is the frontier; one hundred years later, given the genius of technology and the arithmetic of population, you end up with the crowds, and the bad air, and the fish floating in the rivers. The transformation is commonly called progress, and some of the people here fear it.

I remember that in Anchorage last autumn the women’s voices were the most wistful. The Legislature, in hopes of providing a rationale for its subsequent laws and distributions, summoned a preliminary conference to which it invited people from everywhere in the state. For three days I listened to teachers, Eskimos, bankers, Tlingit Indians, fishermen, petroleum engineers, guides, housewives, newspaper editors, and bush pilots. It was as if they were afraid of the consequences of the money. They kept talking about ‘Alaska the way it is now’ and ‘all those things we came up here to get away from.’ The politicians assured them that their fears were irrational, that Alaska must take its place in the twentieth century.

At the end of the conference I remember a woman standing uncertainly in the lobby of the Captain Cook Hotel; she was holding a sheaf of government papers of which she seemed suspicious, as if the pretentious language (‘parameters,’ ‘time-frames,’ ‘infrastructure,’ etc.) somehow announced impending ruin.

‘I listen to them talk,’ she said, ‘and I hear the trees falling in the forest.’

Tonight it is snowing, and perhaps I’m giving way to the pessimism of the weather; tomorrow I begin with debate in the State Senate.”