Like Michel Siffre, who embedded himself in caverns and glaciers decades ago to test the human limits in isolation in advance of Apollo missions, journalist Kate Greene spent four months training in the exquisite malaise of a simulated NASA Mars mission in Hawaii, lying in wait–for what?–near the silent mouth of a volcano. It was so much like sleep that dreams–or something like them–began. The opening of “Planet Boredom,” Greene’s Aeon article about her experience:

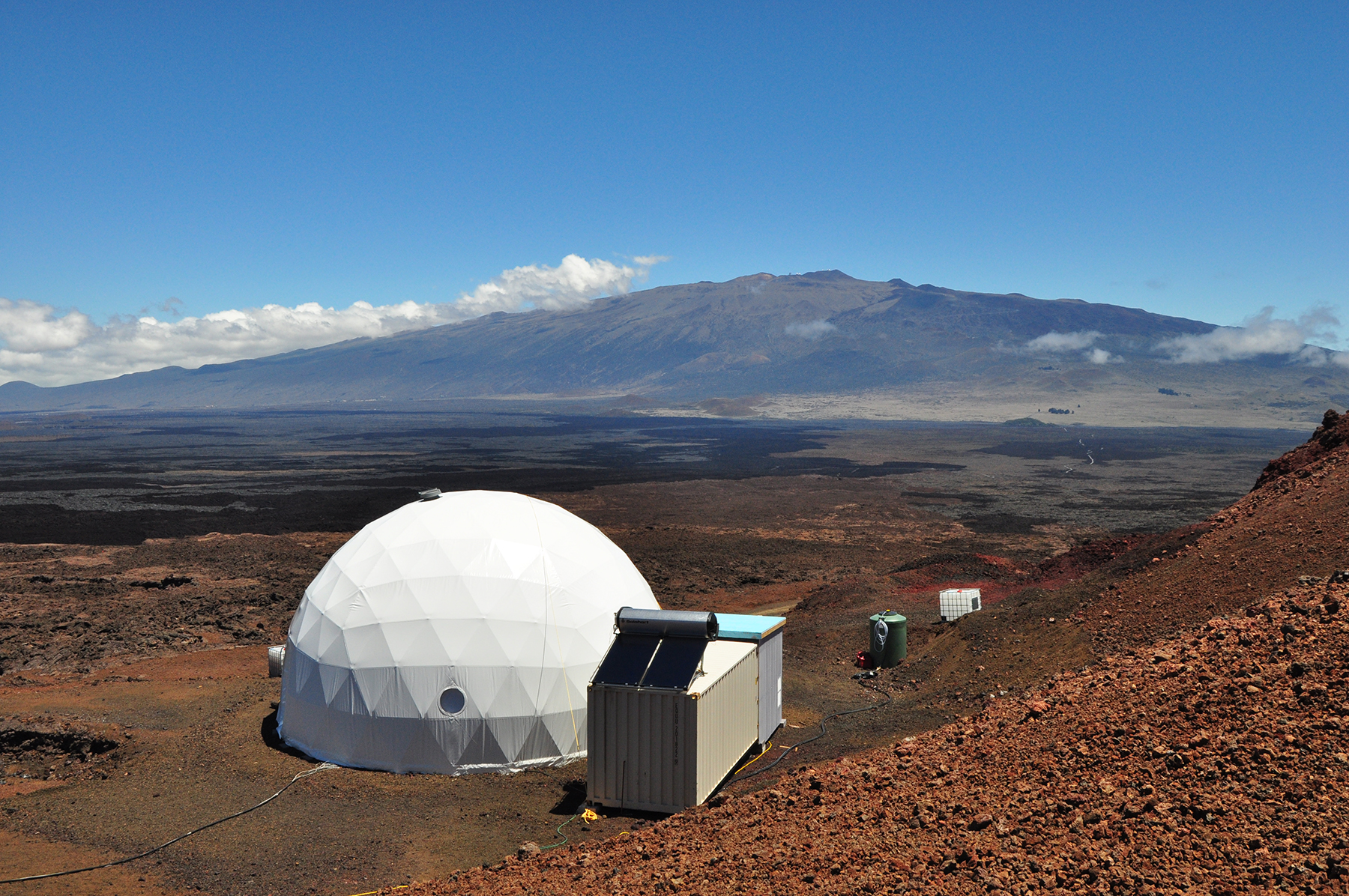

“What follows is an account of an instance where I, a person of relatively sound mind and body, could not believe the evidence before my own eyes. It might not have been a hallucination that I experienced, but it was surely a great jolt of consciousness. The scene: I’m in my closet-sized cabin, inside a white dome built to house a crew of six for four months as part of an isolation experiment. As a crew, we are working and living as ‘explorers’ stationed on the surface of ‘Mars’. Our colony is lifelike and NASA-funded, but it is situated in a place quite a bit closer to home, on a remote slope of a Hawai’ian volcano.

It’s only a couple weeks before we are to be released, and I’m sitting on my bed with my laptop, sorting data from a sleep study I’ve been conducting on myself and my crewmates for the past three months. My cabin door is open. From the corner of my eye, I see a stranger walk into the washroom a few meters away. It’s odd, I think, for a stranger to be here. Our doors are not locked during the day, but our habitat is positioned in an isolated area, at a high elevation, far away from paved roads and pedestrians. The sight of an unfamiliar person nonchalantly using our facilities is enough to jack up my senses to high alert.

I watch as the stranger goes into the washroom and splashes water on his face. Do I know him? Why can’t I tell? If he is an intruder, why is he here? And what will he do when he’s done freshening up and sees me staring at him? I have three male crewmates and the man washing his face looks like none of them. Our crew commander shaves his head while this man has thick brown hair, slicked back. Another crewmate almost always wears buttoned-up long-sleeved shirts. The stranger is in a baggy black T-shirt. My third male crewmate is larger than the unfamiliar man and has curly red hair and a beard. This man is clean-shaven.

Finally, the stranger steps out of the bathroom and confronts me. ‘What,’ he says, less a question, more a bark. His voice kicks me to reality. It’s Simon, our red-headed engineer who has evidently shorn his beard and lost more weight over the mission than I had previously noticed.

Still, my heart is racing and a surge of blood warms me from earlobe to fingertip. ‘I didn’t know who you were,’ I say. He nods and gives a slight smile. We both laugh uneasily at the absurd thought of an intruder. It’s almost too impossible for us to imagine.

And it was shortly thereafter, as the tail end of my terror entwined with the emergent joy of relief, that I notice I hadn’t felt anything so strongly in months. I had been living in a kind of torpor.”