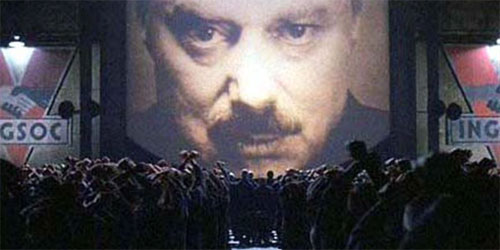

This is happening in Venezuela right now. If the #DeepState succeeds in ousting @realDonaldTrump, expect the same. pic.twitter.com/HC7wBOc0ys

— Julian Assange 🔹 (@JulianAssanje) August 4, 2017

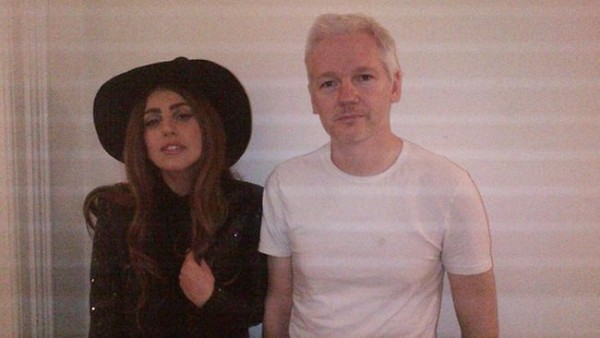

Julian Assange was always a dubious character, but he probably didn’t begin his Wikileaks career as a Putin puppet. That’s what he’s become during this decade, however, helping the Kremlin tilt the 2016 U.S. Presidential election with coordinated leaks and serving in the post-election period as a defender of Donald Trump, as the Commander-in-Chief attempts to gradually degrade liberty and instill authoritarianism in America.

Assange’s most recent gambit was to warn of mass violence in the U.S.–encourage it, actually–by promising that the disaster unfolding in Venezuela would be replicated here should Trump be ousted from office for any number of nefarious acts that may be uncovered by Robert Mueller or other investigative officials. The analogy is dishonest since Venezuela’s decline is the result of gross mismanagement, not any political conflict. But large-scale civil unrest in America would be an ideal outcome for the Kremlin, which longs to destabilize the most powerful democracies.

Venezuela is going through a crazy-dangerous moment, for sure, and while the U.S. has a markedly different history and traditions, we could certainly will slide further toward such a nightmare if Trump and Assange get their way.

· · ·

The opening of Hannah Dreier’s harrowing AP report of her last days covering Venezuela’s fresh hell:

CARACAS, Venezuela (AP) — The first thing the muscled-up men did was take my cellphone. They had stopped me on the street as I left an interview in the hometown of the late President Hugo Chavez and wrangled me into a black SUV.

Heart pounding in the back seat with the men and two women, I watched the low cinderblock homes zoom by and tried to remember the anti-kidnapping class I’d taken in preparation for moving to Venezuela. The advice had been to try to humanize yourself.

“What should we do with her?” the driver asked. The man next to me pulled his own head up by the hair and made a slitting gesture across his throat.

What might a humanizing reaction to that be?

I had thought that being a foreign reporter protected me from the growing chaos in Venezuela. But with the country unraveling so fast, I was about to learn there was no way to remain insulated.

I came to Caracas as a correspondent for The Associated Press in 2014, just in time to witness the country’s accelerating descent into a humanitarian catastrophe.

Venezuela had been a rising nation, buoyed by the world’s largest oil reserves, but by the time I arrived, even high global oil prices couldn’t keep shortages and rapid inflation at bay.

Life in Caracas was still often marked by optimism and ambition. My friends were buying apartments and cars and making lofty plans for their careers. On weekends, we’d go to pristine Caribbean beaches and drink imported whiskey at nightclubs that stayed open until dawn. There was still so much affordable food that one of my first stories was about a growing obesity epidemic.

Over the course of three years, I said good-bye to most of those friends, as well as regular long-distance phone service and six international airline carriers. I got used to carrying bricks of rapidly devaluing cash in tote bags to pay for meals. We still drove to the beach, but began hurrying back early to get off the highway before bandits came out. Stoplights became purely ornamental because of the risk of carjackings.

There was no war or natural disaster. Just ruinous mismanagement that turned the collapse of prices for the country’s oil in 2015 into a national catastrophe.

As things got worse, the socialist administration leaned on anti-imperialist rhetoric. The day I was put into the black SUV in Chavez’s hometown of Barinas coincided with a government-stoked wave of anti-American sentiment. The Drug Enforcement Administration had just jailed the first lady’s nephews in New York on drug trafficking charges, and graffiti saying “Gringo, go home” went up around the country overnight. An image of then-President Barack Obama with Mickey Mouse ears appeared on the AP office building.

I was trying to make small talk with the men who had grabbed me when we pulled past a high, barbed wire-topped wall, and I glimpsed the logo of the secret police. Flooded with relief, I realized I hadn’t been kidnapped, just detained.

Inside, the men trained a camera on me for an interrogation. One said that I would end up like the American journalist who had recently been beheaded in Syria. Another said if I gave him a kiss I could go free.

The man who had been driving said they would be keeping me until the DEA agreed on a swap for the first lady’s nephews. He accused me of helping sabotage the economy. “How much does the U.S. pay you to be their spy?” he asked.

The government of President Nicolas Maduro blames the U.S. and right-wing business interests for the economic collapse, but most economists say it actually stems from government-imposed price and currency distortions. There often seemed to be a direct line between economic policy and daily hardship. One week, the administration declared that eggs would now be sold for no more than 30 cents a carton. The next week, eggs had disappeared from supermarkets, and still have not come back.•