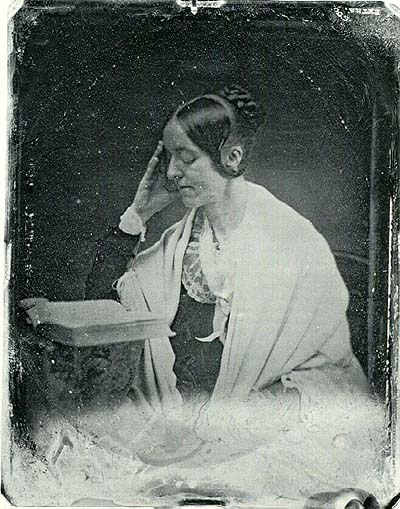

Margaret Fuller (1810-1850) was the Susan Sontag of her day–America’s original Susan Sontag, actually. The first female book critic of great acclaim, Fuller was not exactly modest about her brilliance. “I find no intellect comparable to my own,” she offered to all who would listen. She was a prominent member of Brook Farm, George Ripley’s failed experiment in Utopian living, and reportedly inspired the “Zenobia” character in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance, who commits suicide by drowning. Fuller herself died by water, perishing in a shipwreck that she seemingly could have escaped but chose not to. Her body was never recovered. Some 35 years after her death, an odd (and likely apocryphal) story appeared about her in the Boston Traveller, which was reprinted in the September 6, 1885 Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The article in full:

“As every topic comes up at the elegant lunch and dinner tables of Newport, so I was not astonished to hear a lady say that she ‘knew of the grave of Margaret Fuller.’ Mrs. Julia Ward Howe, who was present, and who had written a life of Margaret Fuller, was astonished, as it is reputed in all the lives written of that extraordinarily resurrected person, the Marchesi Ossili, that her body never reached land. An old fisherman at Fire Island, however, told a lady who was in the habit of going there several years ago, that he found the remains of Margaret Fuller lying on the beach in her nightgown, which was marked by her name, and that he wrote to the brothers Fuller and Horace Greeley about it, without receiving any answer; that he went up to New York to see Mr. Greeley, but he seemed to take no notice of the fact; and that he then buried Margaret Fuller at Coney Island; and could identify the spot.”