Few things make me sadder than Muhammad Ali being unable to speak. By the time I discovered him in my childhood, he was at the very end of his career, a legend but washed up, already slurring his speech, his motor skills screeching to a halt. For all his flaws, Ali still seemed immaculate, and I became obsessed with him. (I may have watched a.k.a. Cassius Clay a hundred times.) But I didn’t become a boxing fan because of his shaky, then quieted, voice.

So, I never paid close attention to the spectacle of Mike Tyson, the last amazing heavyweight, though it was hard to completely recuse yourself from his greatness and his badness. As Norman Mailer astutely reported, Tyson was the uneasy king of what were really just gaudy, late-century cockfights, a man crumbling inside of a sport that was crumbling.

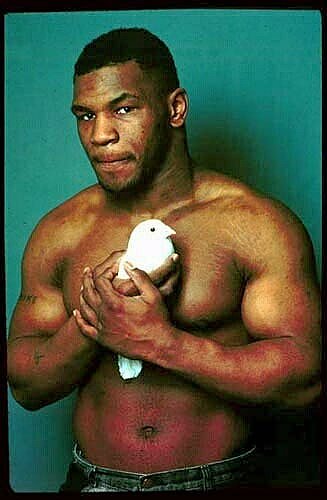

Mike Tyson is sad for reasons beyond the usually depressing second act of retired boxers, as they endure the slowing of brains that have been treated like speed bags. His reckoning is America’s reckoning. He’s the son of broken promises, of neglect, even of the failure of our best efforts. Raised first by a prostitute and then in the cages of Spofford, he was the boy who could only really love pigeons, and later he was the chicken that came home to roost.

From Joyce Carol Oates’ New York Review of Books piece about the autobiography Tyson has co-authored with Larry Sloman:

Mike Tyson, at twenty the youngest heavyweight champion in history, and in the early, vertiginous years of his career a worthy successor to Ali, Louis, and Jack Johnson, has managed to reconstitute himself after he retired from boxing in 2005 (when he abruptly quit before the seventh round of a fight with the undistinguished boxer Kevin McBride). He became a bizarre replica of the original Iron Mike, subject of a video game, cartoons, and comic books; a cocaine-fueled caricature of himself in the crude Hangover films; star of a one-man Broadway show directed by Spike Lee, titled Undisputed Truth, and the HBO film adaptation of that show; and now the author, with collaborator Larry Sloman, of the memoir Undisputed Truth.

In his late teens in the 1980s Mike Tyson was a fervently dedicated old-style boxer, more temperamentally akin to the boxers of the 1950s than to his slicker contemporaries. In his forties, Tyson looks upon himself with the absurdist humor of a Thersites for whom loathing of self and of his audience has become an affable shtick performance. He liked to come on as crazed and dangerous, screaming in self-parody at press conferences:

I’m a convicted rapist! I’m an animal! I’m the stupidest person in boxing! I gotta get outta here or I’m gonna kill somebody!… I’m on this Zoloft thing, right? But I’m on that to keep me from killing y’all…. I don’t want to be taking the Zoloft, but they are concerned about the fact that I’m a violent person, almost an animal. And they only want me to be an animal in the ring.•