In a New York Times report by Benedict Carey about lessons learned at the inaugural Extreme Memory Tournament, which was held recently in San Diego, the upshot is not that some have remarkably elastic recall, but that they thrive at visualization and focus. I would still think, however, that such abilities are more pronounced in some brains than others. An excerpt:

“‘We found that one of the biggest differences between memory athletes and the rest of us,’ said Henry L. Roediger III, the psychologist who led the research team, ‘is in a cognitive ability that’s not a direct measure of memory at all but of attention.’

The technique the competitors use is no mystery.

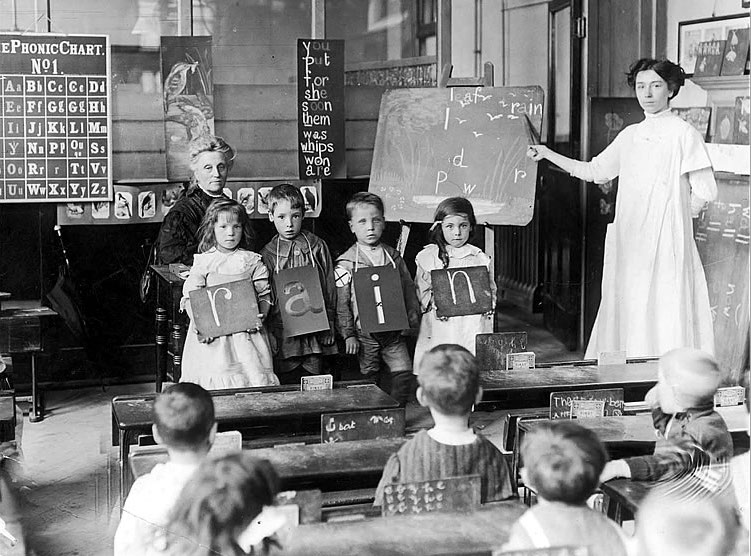

People have been performing feats of memory for ages, scrolling out pi to hundreds of digits, or phenomenally long verses, or word pairs. Most store the studied material in a so-called memory palace, associating the numbers, words or cards with specific images they have already memorized; then they mentally place the associated pairs in a familiar location, like the rooms of a childhood home or the stops on a subway line.

The Greek poet Simonides of Ceos is credited with first describing the method, in the fifth century B.C., and it has been vividly described in popular books, most recently Moonwalking With Einstein, by Joshua Foer.

Each competitor has his or her own variation. ‘When I see the eight of diamonds and the queen of spades, I picture a toilet, and my friend Guy Plowman,’ said Ben Pridmore, 37, an accountant in Derby, England, and a former champion. ‘Then I put those pictures on High Street in Cambridge, which is a street I know very well.’

As these images accumulate during memorization, they tell an increasingly bizarre but memorable story. ‘I often use movie scenes as locations,’ said James Paterson, 32, a high school psychology teacher in Ascot, near London, who competes in world events. ‘In the movie Gladiator, which I use, there’s a scene where Russell Crowe is in a field, passing soldiers, inspecting weapons.'”