Speaking of Joseph Engelberger, here’s the opening of a 1982 NYT article by Barnaby J. Feder and a video about the recently deceased roboticist’s development of the machine caretaker, ISAAC, which was meant to help astronauts and disabled people alike in completing tasks. It could roll, lift, cook and talk a little. It was a first-phase project done in conjunction with NASA and at the time promised that “when a more svelte Mark II goes into production, it will serve everyday around the clock at a cost of approximately $1.00 per hour.” That was supposed to occur in the 1990s, though the target date was too aggressive.

From Feder:

DANBURY, Conn. — FOUR decades ago, science fiction writer Isaac Asimov’s robot stories caught the imagination of a Columbia University physics student named Joseph F. Engelberger. Sometime in 1985, a robot named in Mr. Asimov’s honor is likely to be serving coffee to Mr. Engelberger and other directors of the nation’s first and largest industrial robot manufacturer.

Now a prototype in the company’s research laboratory, Isaac the Robot is being designed to do more than traverse the board room serving coffee. Mr. Engelberger also wants Isaac to provide snacks prepared in the adjoining kitchen’s microwave oven and wash dishes.

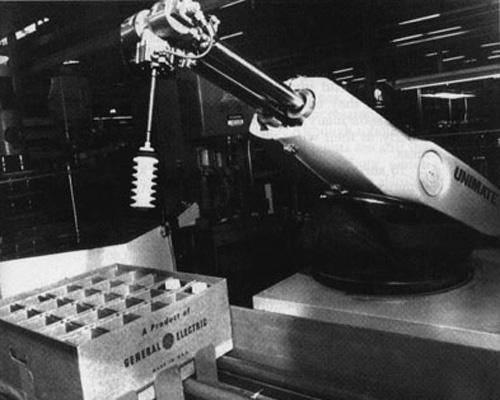

Mr. Engelberger’s company, Unimation Inc., has no plans to market Isaac, or similar robots, but Isaac is more than just a whimsical tribute to Mr. Asimov. Mr. Engelberger envisions Isaac – a mobile, improved version of the programmable manipulator, or PUMA robot, the company already sells – as the forerunner of a new generation of domestic and commercial service robots that Unimation and other robotics companies will begin selling during the 1990’s.

The right to be an out-of-the-closet visionary is one of the relished and hard-won benefits that the 56-year-old Mr. Engelberger has earned for his pivotal role in bringing the robot industry to life, both in the United States and abroad.

Actually, it was George C. Devol, not Mr. Engelberger, who developed and patented the basic technology on which the industry is founded. But since meeting Mr. Devol in 1956, Mr. Engelberger has preached the gospel that ”smart” machines were the key to getting people out of dangerous or tedious production jobs and a key to improving productivity. And his company, a subsidiary of the Condec Corporation of Old Greenwich, Conn., turned out the first robots that industry was willing to buy.

As a result, no robotics gathering today would be considered complete without the presence of the crew-cut, bow-tied Mr. Engelberger and his blunt observations about competitors, customers and robots themselves. ”He is as important to the industry as he is to the company, in some respects more so,” said Laura Conigliaro, the Bache Halsey Stuart Shields analyst who is Wall Street’s best known robotics expert. ”He is a spokesman and a showman, and he is good at it.”

”He was the one that listened,” said Mr. Devol, who now runs a robot leasing and consulting business from his home in Fort Ladderdale, Fla. Mr. Devol recalls numerous efforts to interest established companies in his work, including some, such as I.B.M., that have recently entered the now rapidly growing robotics field.

”George Devol was unable to restrain himself from spilling the whole dream out, which scared most businessmen off,” said Mr. Engelberger during an interview last week at Unimation’s headquarters. ”I kept myself from talking about some of the things that have happened, which he envisioned.”

The ”whole dream” is emerging now that robots have achieved acceptance in an increasing variety of industrial tasks – from materials handling to painting and welding – and are rapidly being improved to the point that more difficult jobs, such as assembly, will be economically feasible. More important, as computer-machine tool hybrids capable of being reprogrammed to adapt to changing conditions, they have been recognized as a key building block in the flexible, highly automated factory of the future.

It took American industry a long time to catch on.•

______________________________

“ISSAC, Will You Please Help Me Up?”