Kris Jenner is the new Joe Jackson, and a big ass the new moonwalk.

We don’t have to like what the Kardashian-Jenner clan tells us about our era, but to deny their significance in it–what exactly do those people do?–is to miss the point. From Reality TV to Netflix algorithmic ratings to likes and retweets, the fans, those barbarians, have stormed the gates, overturning the professional class.

Bill Simmons was part of that revolution, bringing a spectator’s passion (along with writing chops and a funny, if sometimes sexist, sense of humor) to a field that had long been called the “sports pages.” The Internet was his playing field and it graduated him from Boston cheap seats to Los Angeles courtside, a progression that never completely sat right.

Now that his run at ESPN has finished ingloriously, here are two passages from Jonathan Mahler’s prescient 2011 New York Times Magazine piece, “Can Bill Simmons Win the Big One?” The first focuses on the rise of the fan and the other on the likely bitter ending of a stormy if mutually profitable relationship.

__________________________

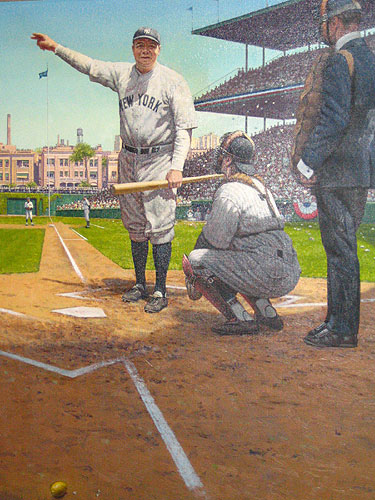

A brief, reductive history of modern sportswriting in America might look something like this: Practitioners of the craft during the first two-thirds of the 20th century paid for their unfettered access to athletes by glorifying them, “Godding up those ballplayers,” as one sportswriter memorably put it. In the 1970s, sportswriters stopped protecting athletes and started demythologizing them. As they did, their access diminished. The gulf between ballplayers and fans widened.

Enter Simmons and his legion of imitators, whom you won’t find loitering in a locker room, trawling for quotes or sitting at the press tables of an N.B.A. game, where rooting is forbidden. At the center of Simmons’s columns is not the increasingly unknowable athlete but the experience of the fan. His frame of reference is himself. He might not be able to tell you how a ballplayer felt performing a particular feat, but he can tell you how he felt watching it, what childhood memories it evoked, the scene from the movie “Point Break” it brought to mind, which one of his countless theories — newcomers to his column can consult a glossary on his home page — it vindicates. There’s a vaguely metaphysical quality to this approach: the sportswriter Robert Lipsyte calls it “the tao of Bill.”

Simmons is more than just a fan; he is the fan, the voice of the citizenry of sports nation. In a larger sense, what he’s doing is nothing new. In much the same way that newspaper columnists call out callous politicians and crooked businessmen, Simmons rails against greedy owners, the commissioners who invariably side with them, overpaid players and dysfunctional franchises. Recently, he lambasted the Maloof brothers, the owners of the Sacramento Kings, for neglecting the team, and David Stern, the N.B.A.’s commissioner, for allowing them to do so. “Once you get approved to purchase an N.B.A. franchise, for whatever reason, David Stern seemingly yields all control over your behavior unless you criticize his officials,” Simmons wrote. “Anything else? Knock yourself out. Buying into the N.B.A. is like buying a house: Once you move in, feel free to disgrace the neighborhood however you want.”Simmons is a funny, intelligent and original writer. He comes up with surprising angles and conceits — in a column last month, he applied quotes from “The Wire” to moments in the N.B.A. playoffs — that may not always work but certainly prevent him from becoming predictable. He is especially good at describing sports moments, a dying art since the arrival of nonstop sports highlights.

But Simmons’s rise has been fueled by broader forces too. The recent explosion of the sports industry — the emergence of 24-hour sports networks, sports-radio shows, Web sites, fantasy leagues, video games — has been geared foremost toward creating and satisfying the demands of the consumer. The fan became the engine of the sporting world.

__________________________

It was a sultry afternoon, and midway through the game, we went inside to the Dugout Club to cool off and talk. Simmons sounded as if he was having some regrets about Grantland. “It hasn’t been as much as fun as I had thought,” he told me. “I’m not sure I would do it again.” Too much of his time was being spent in the office, dealing with administrative tasks, which was encroaching on his column.

Simmons’s literary persona suggests a slacker, a guy who would like nothing more than to spend his days drinking beer and watching sports. This image, enhanced by his loose, casual prose, is misleading. The real Simmons is hard-working and competitive. His rise to prominence has been punctuated by bouts of restlessness and frustration, even when things looked from the outside to be going his way. He’s still chafing over his publisher’s handling of his 2009 book, The Book of Basketball, a No. 1 New York Times best seller.

As far as Simmons has come since he first started searching for an audience, he wants to go much further, to create something more enduring than his column or even his books. But the drudgery of running his own publication is already intruding on the utopian world he has built for himself. And he knows that the only thing preventing him from becoming another overexposed hack, an ex-sportswriter who now gets paid to blather on TV, is his column, which can take days to research and write. “My biggest concern about the site is that I don’t want the column to just be one of the things I’m doing,” Simmons said.

After the game, we drove to Chinatown for a late lunch. “Listen to this,” Simmons said, reading the fortune from his cookie as we were getting up to leave: “An important business venture may soon develop for you.” Everyone laughed. “Or it could be the end of my career,” Simmons joked. “I don’t know, I think I have one more big sellout contract in me.”•