It sometimes seems that Monica Lewinsky was the last American with a sense of shame. It did not benefit her.

Celebutantes with sex tapes have since sold their boldface indiscretions for countless millions and covered Vogue. Most of them have a short shelf life, falling not soon after rising, but the Kardashians have taken Andy Warhol’s fifteen minutes of fame and broken the hands off the clock, becoming our other First Family. They are not ashamed.

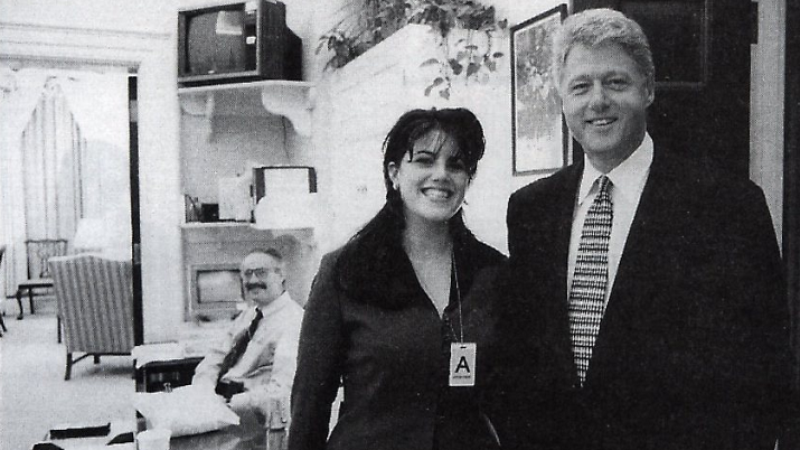

Lewinsky, shaped by the pre-Internet Era, was not proud of her acts with the leader of the free world. She has never fully escaped the dark shadow of infamy, having spent her formative years mocked for her morals and weight, for being the girl in the beret used like a White House humidor. Just imagine the dumbest thing you did when you were 22 put on blast for the entire world. It’s unthinkable for anyone not raised on selfies and social media to survive such a thing, to flourish. Before everyone lived in public, privacy was prized, reputations mattered. It’s better in the big picture that the next generations don’t have to be ruined anymore by trolls. They just own it, whatever “it” may be. Something, though, has been lost in translation.

In a smart Guardian piece, Jon Ronson profiles the former intern in middle age. The opening:

One night in London in 2005, a woman said a surprisingly eerie thing to Monica Lewinsky. Lewinsky had moved from New York a few days earlier to take a master’s in social psychology at the London School of Economics. On her first weekend, she went drinking with a woman she thought might become a friend. “But she suddenly said she knew really high-powered people,” Lewinsky says, “and I shouldn’t have come to London because I wasn’t wanted there.”

Lewinsky is telling me this story at a table in a quiet corner of a West Hollywood hotel. We had to pay extra for the table to be curtained off. It was my idea. If we hadn’t done it, passersby would probably have stared. Lewinsky would have noticed the stares and would have clammed up a little. “I’m hyper-aware of how other people may be perceiving me,” she says.

She’s tired and dressed in black. She just flew in from India and hasn’t had breakfast yet. We’ll talk for two hours, after which there’s only time for a quick teacake before she hurries to the airport to give a talk in Phoenix, Arizona, and spend the weekend with her father.

“Why did that woman in London say that to you?” I ask her.

“Oh, she’d had too much to drink,” Lewinsky replies. “It’s such a shame, because 99.9% of my experiences in England were positive, and she was an anomaly. I loved being in London, then and now. I was welcomed and accepted at LSE, by my professors and classmates. But when something hits a core trauma – I actually got really retriggered. After that I couldn’t go more than three days without thinking about the FBI sting that happened in ’98.”

Seven years earlier, on 16 January 1998, Lewinsky’s friend – an older work colleague called Linda Tripp – invited her for lunch at a mall in Washington DC. Lewinsky was 25. They’d been working together at the Pentagon for nearly two years, during which time Lewinsky had confided in her that she’d had an affair with President Bill Clinton. Unbeknown to Lewinsky, Tripp had been secretly recording their telephone conversations – more than 20 hours of them. The lunch was a trap.•