Jon Gertner, who wrote an excellent book about Bell Labs, has an article at Fast Company about Google X, the lab that is trying to be its creative descendant, though the search giant’s “moonshot” wing is even further afield, more an amorphous thing than something that is solid state. An excerpt:

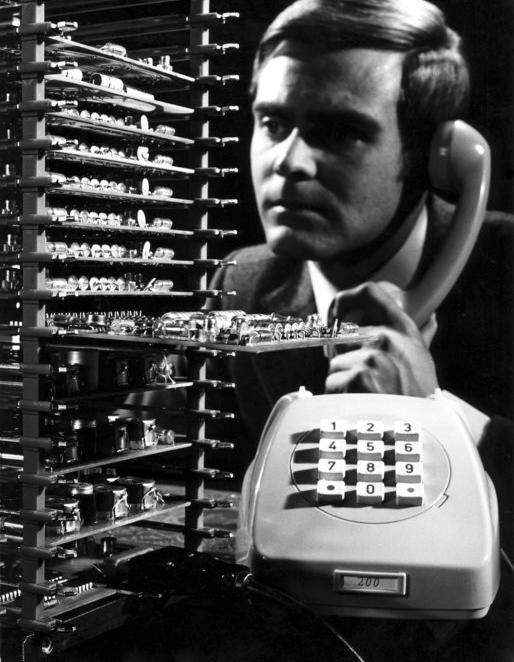

“X does not employ your typical Silicon Valley types. Google already has a large lab division, Google Research, that is devoted mainly to computer science and Internet technologies. The distinction is sometimes framed this way: Google Research is mostly bits; Google X is mostly atoms. In other words, X is tasked with making actual objects that interact with the physical world, which to a certain extent gives logical coherence to the four main projects that have so far emerged from X: driverless cars, Google Glass, high-altitude Wi-Fi balloons, and glucose-monitoring contact lenses. Mostly, X seeks out people who want to build stuff, and who won’t get easily daunted. Inside the lab, now more than 250 employees strong, I met an idiosyncratic troupe of former park rangers, sculptors, philosophers, and machinists; one X scientist has won two Academy Awards for special effects. [Astro] Teller himself has written a novel, worked in finance, and earned a PhD in artificial intelligence. One recent hire spent five years of his evenings and weekends building a helicopter in his garage. It actually works, and he flew it regularly, which seems insane to me. But his technology skills alone did not get him the job. The helicopter did. ‘The classic definition of an expert is someone who knows more and more about less and less until they know everything about nothing,’ says DeVaul. ‘And people like that can be extremely useful in a very focused way. But these are really not X people. What we want, in a sense, are people who know less and less about more and more.’

If there’s a master plan behind X, it’s that a frictional arrangement of ragtag intellects is the best hope for creating products that can solve the world’s most intractable issues. Yet Google X, as Teller describes it, is an experiment in itself–an effort to reconfigure the process by which a corporate lab functions, in this case by taking incredible risks across a wide variety of technological domains, and by not hesitating to stray far from its parent company’s business. We don’t yet know if this will prove to be genius or folly. There’s actually no historical model, no precedent, for what these people are doing.”