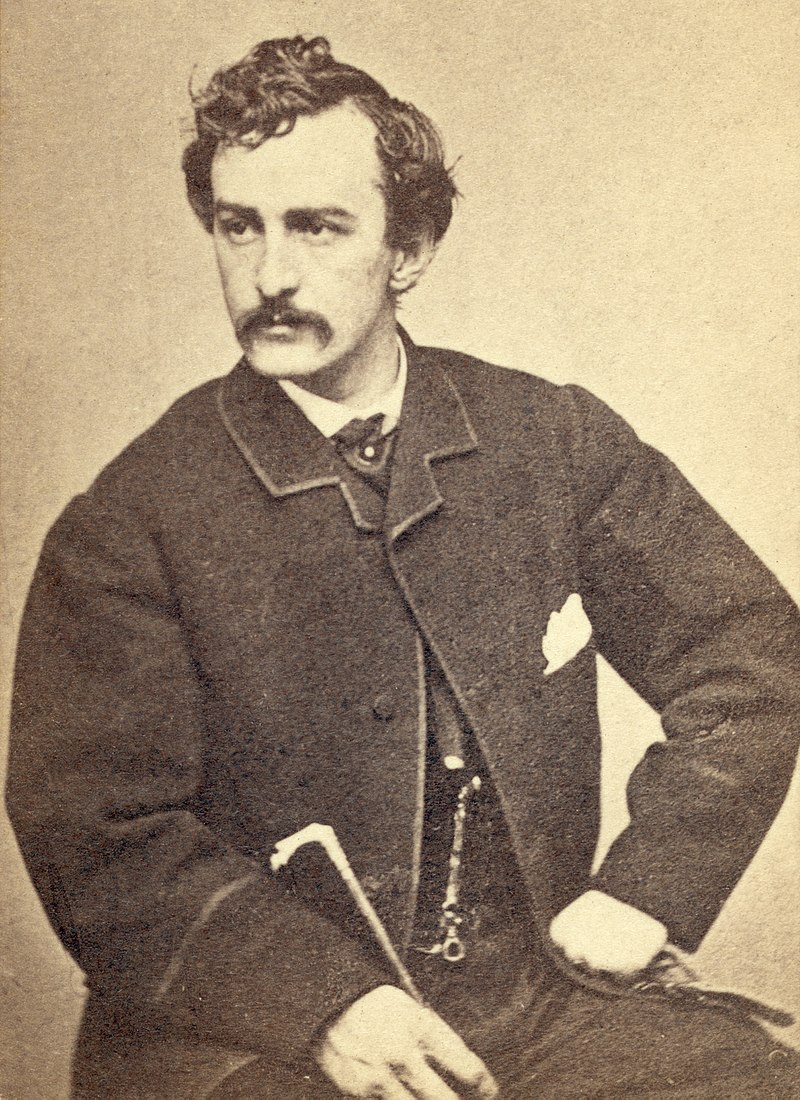

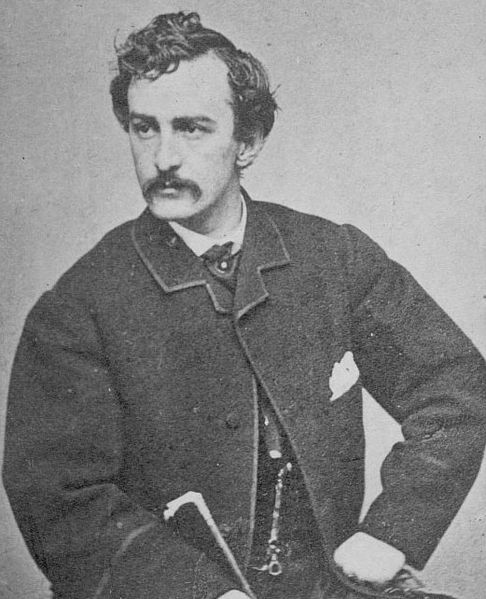

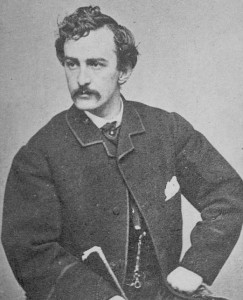

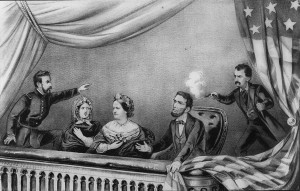

Sometime after January 2008, an entertainer became obsessed with the President of the United States, determined to prove him invalid and unworthy, to destroy the legacy of someone far grander than himself. Politics was part of the impetus, but the mania seemed to have a far deeper source. A similar scenario played out more than 140 years earlier with far more lethal results when another entertainer, John Wilkes Booth, was overcome by a determination to kidnap or kill Abraham Lincoln, even directing angry dialogue at the President when he happened to attend a play in which his future assassin performed. “He does look pretty sharp at me, doesn’t he?” the President acknowledged. The thespian was a Confederate sympathizer, but his wild rage for Lincoln was driven by something beyond the question of abolition.

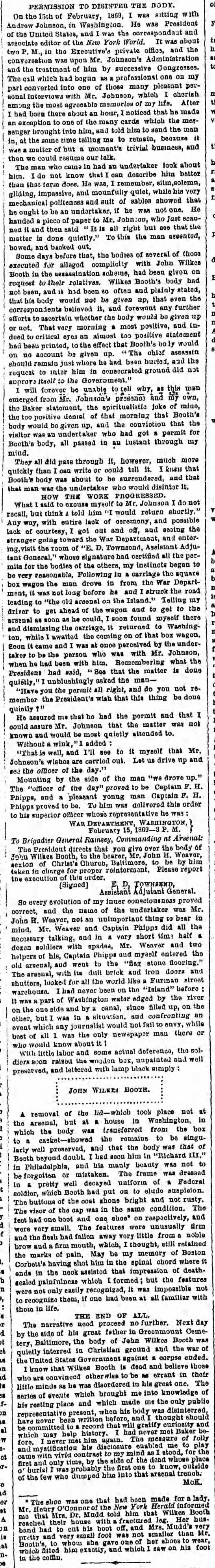

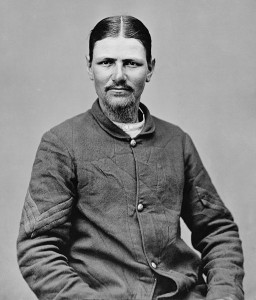

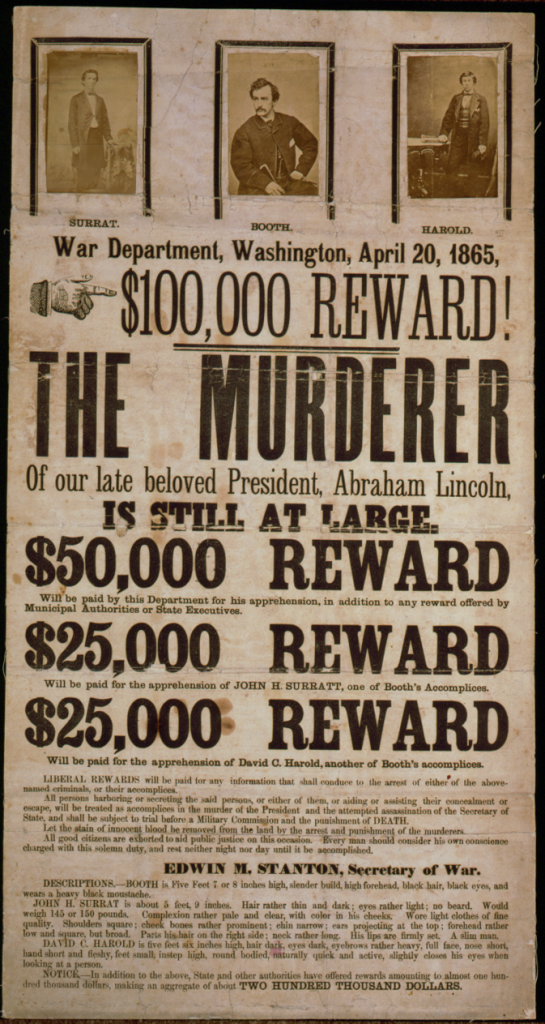

In the aftermath of the 1865 balcony tragedy, Booth fled and was slain by the gun of Union soldier Boston Corbett and interred in D.C. after an autopsy and the removal of several vertebrae and the fatal bullet. The body was subsequently relocated to a warehouse at the Washington Arsenal. Four years after he met with justice, the actor’s corpse was emancipated from government oversight and was allowed to be reburied in Baltimore by his family. A Brooklyn Daily Eagle reporter happened to be visiting with President Johnson in the White House when the transfer was made, allowing him to be eyewitness to the grim process and the state of the remains, which he said retained much of the departed’s “manly beauty.” An article in an 1877 edition of the paper recalled the undertaking.