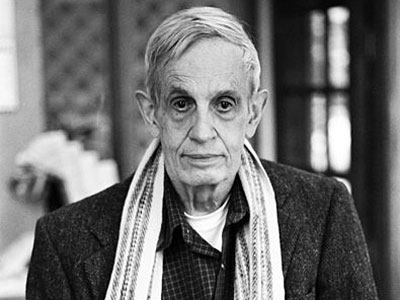

I think the best postscript I’ve read to the unfortunate auto crash that just claimed the lives of John and Alicia Nash is the Q&A Zachary A. Goldfarb of the Washington Post conducted with Sylvia Nasar, author of the wonderful book about the mathematician, A Beautiful Mind, which was masterfully adapted for the screen by Akiva Goldsman. In one exchange, Nasar reminds that even the relatively happy third act of Nash’s life was complicated. An excerpt:

Zachary A. Goldfarb:

How did he spend the last 21 years, since he won the Nobel?

Sylvia Nash:

The first time I saw him was a few months after he won the Nobel, and he was going to a game theory conference in Israel. He was surrounded by other mathematicians, and he looked like someone who had been mentally ill. His clothes were mismatched. His front teeth were rotted down to the gums. He didn’t make eye contact. But, over time, he got his teeth fixed. He started wearing nice clothes that Alicia could afford to buy him. He got used to being around people.

He and Alicia spent a lot of their time taking care of their son, Johnny, and doing the things that are so ordinary that the rest of us don’t think about them. Once I asked him what difference the Nobel Prize money made, and he literally said, “Well, now I can go into Starbucks and buy a $2 cup of coffee. I couldn’t do that when I was poor.” He got a driver’s license. He had lunch most days with other mathematicians, reintegrating into the one community that mattered to him most.

The last time I was with him was about a year ago when Alicia organized a really lovely dinner with us and two other couples. John was talking about all the invitations they’ve gotten and all the places they’ve planned to travel. Johnny was there. He was still very sick. They took him to a lot of the places they went and always tried to include him. Their life was a mix of glamour and celebrity – and the day-to-day which revolved around Johnny, who by then was in his 50s and was as sick as his father ever was and entirely dependent on them.•