Had hoped that Nikkei’s purchase of the Financial Times meant the venerable British paper was on higher ground, safe from drowning in red ink like many of the best publications. But it would seem to not be so.

Automation has lately been offered as a lifesaver for the sinking industry, but it’s galling when that transformation is sold as something wonderful for journalists themselves. That’s very unlikely. Jobs will disappear, and while some human intelligence will be augmented, enough will be replaced to leave a bruise. The “worst job in America” may improve for a few lucky souls, but they’ll likely feel increasingly lonely.

Bloomberg is the latest company to promote “automated journalism” as a win-win proposition, though the final score may be much more uneven. A transcript of company EIC John Micklethwait’s memo on the initiative, which was reported by Benjamin Mullin at Poynter.org:

I want to dedicate virtually all this week’s note to an incredibly important subject: automation. I think it is crucial to the future of journalism in a much broader way than many of us realize: It certainly stretches much further than just generating headlines. If we embrace it as a newsroom, apply the brains of our 2,400 journalists and analysts as well as the values of independence, transparency and rigor that Bloomberg’s journalism at its best exemplifies, then we can lead the rest of our industry — and write a lot of amazing stories in the process.

We already use automation quite a lot — to alert our readers to news, to customize news and to spot trends. It plays a big role in many of our new initiatives: In Daybreak, it will let customers tailor their morning news; our equity Movers project relies on computers to tell us when a share has jumped or sunk; Project Cyborg is helping our editors send headlines this earnings season on hundreds of U.S. companies; and computers are helping us instantly translate stories into other languages. But we have only scratched the surface.

So this week we are forming a 10-strong team to lead this initiative. Brad Skillman will head it up from the editorial side and work with our automation czarina, Monique White in News Development, to oversee the creation of smart automated content. The roles available include project coordinators, template writers and engineers. The positions will be posted on {PATH }. We will set up a dedicated wire for some of our stories; in other cases, we will just publish to BN or BFW. Brad, Monique and the group will work with rest of the newsroom to make sure we are tapping our biggest brains for the best ideas. The effort will encompass all of our editorial groups, including BN, BFW and BI. If you have an idea, please take it to them.

Why do we need you, if the basic idea is to get computers to do more of the work? One irony of automation is that it is only as good as humans make it. That applies to both the main types of automated journalism. In the first, the computer will generate the story or headline by itself. But it needs humans to tell it what to look for, where to look for it and to guarantee its independence and transparency to our readers. In the second sort, the computer spots a trend, delivers a portion of a story to you and in essence asks the question: Do you want to add or subtract something to this and then publish it? And it will only count as Bloomberg journalism if you sign off on it. For instance, the computer might be telling you that McDonald’s share price has fallen, while the price of beef has risen. It is up to you to decide whether it is worth writing about this — just as it was up to you to tell the computer to be on the lookout for moves in beef prices.

Done properly, automated journalism has the potential to make all our jobs more interesting. I have written before about journalism moving from covering what has happened to covering why it did. The time spent laboriously trying to chase down facts can be spent trying to explain them. We can impose order, transparency and rigor in a field which is something of a wild west at the moment.•

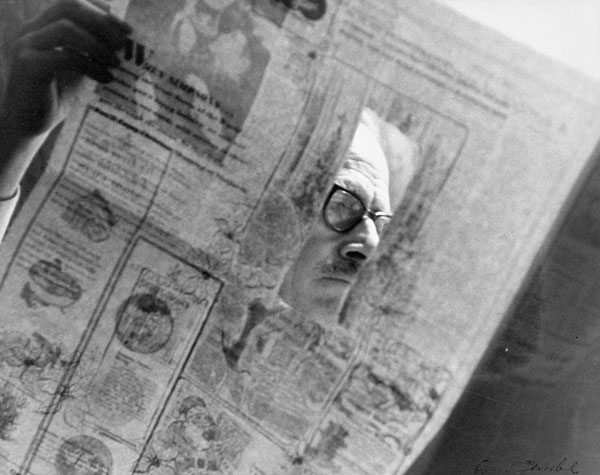

Short documentary from 1961 about the then-futuristic offices of the Miami Herald, a “self-contained city of over 1,200 inhabitants.” It was a time of typewriters, pneumatic tubes and typesetters, when the era of print seemed limitless, before technological efficiency began to destroy the economic model.