More than 20 years after John C. Lilly wrote in LIfe about interspecies communications with dolphins, there were two Omni articles about his work in this area. By the 1980s, computers had entered the discussion.

_________________________

From Owen Davies’ 1983 article “Talking Computer for Dolphins“:

Want to talk to dolphins? The best way may be to talk to a computer first, according to the Human/Dolphin Foundation, in Redwood City, California.

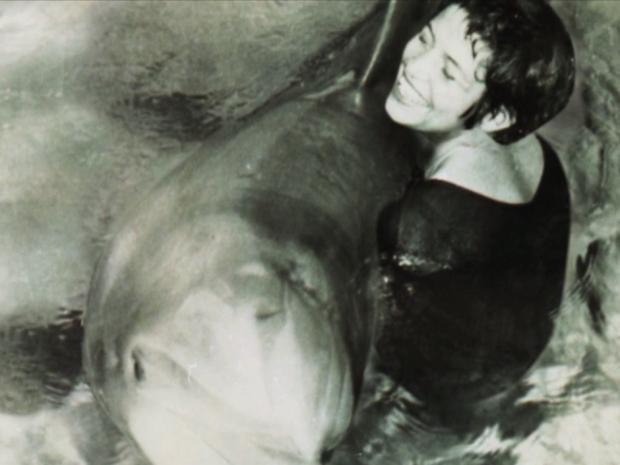

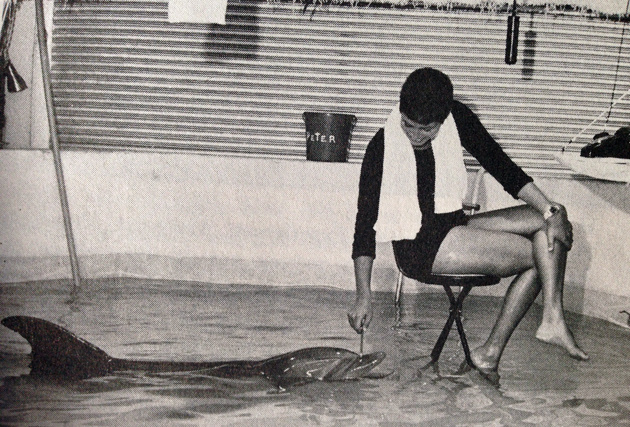

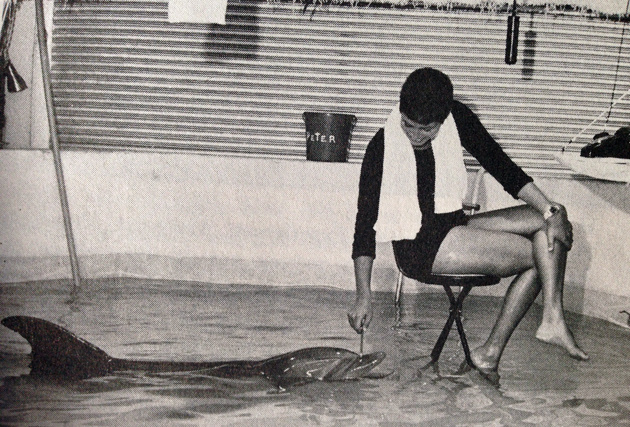

Dr. John Lilly first tried to teach a few dolphins English in the mid-1970s. But Lilly soon found that while the animals were smart, they had trouble under- standing human speech, which uses only a fraction of the enormously wide range of frequencies that dolphins hear. And, although the dolphins tried to speak English, they were physiologically capable of producing only high-pitched, incomprehensible squawks.

Lilly’s answer was to get a computer to translate each species’ speech into sound patterns the other could deal with. In 1977, after three years of work, the foundation developed a computer system capable of translating human words typed on a keyboard into high-frequency sound patterns that dolphins seem to understand; it also analyzed the dolphin sounds and displayed a rough interpretation of them on a computer screen for people to read.

According to physicist John Kert, now working as the foundation’s director, the system is being used to teach dolphins Joe and Rosie simple tasks like jumping, bowing, and recognizing objects on command. The animals have also followed more complex instructions, Kert reports: They can, for instance, swim through a channel to touch a ball with a flipper.

The researchers work with a vocabulary of 30 words, but they soon plan to go up to 128.•

_________________________

From “John Lilly: Altered States,” a 1983 interview by Judith Hooper:

John C. Lilly:

We’re using a computer system to transmit sounds underwater to the dolphins. A computer is electrical energy oscillating at particular frequencies, which can vary. and we use a transducer to convert the electrical waveforms into acoustical energy. You could translate the waveforms into any kind of sound you like: human speech, dolphin-like clicks, whatever.

OMNI::

Do you type something out on the computer keyboard and have it transmitted to the dolphins as sound in their frequency range? And do they communicate back to the computer?

John C. Lilly:

Yes, but we actually use two computers. An Apple II transmits sounds to the dolphins, via a transducer, from a keyboard operated by humans. Then there is another computer, made by Digital Equipment Corporation, that listens to the dolphins. A hydrophone, or underwater microphone, picks up any sounds the dolphins make, feeds them into a frequency analyzer, a sonic spectrum analyzer, and then into the computer. So the computer has an ear and a voice, and the dolphin has an ear and a voice. The system also displays visual information to the dolphins.

On the human side it’s rather ponderous, because we have to punch keys and see letters on a screen. People have tried to make dolphins punch keys, but I don’t think dolphins should have to punch keys. They don’t have these little fingers that we have. So we’d prefer to develop a sonic code as the basis of a dolphin computer language. If a group of dolphins can work with a computer that feeds back to them what they just said — names of objects and so forth — and if we can be the intercessors between them and the computer, I think we can eventually communicate.

OMNI:

How long will it take to break through the interspecies communication barrier?

John C. Lilly:

About five years. I think it may take about a year for the dolphins to learn the code, and then, in about five years we’ll have a human/dolphin dictionary. However, we need some very expensive equipment to deal with dolphins’ underwater sonar. Since dolphins ‘see’ with sound in three dimensions — in stereo — you have to make your words ‘stereophonic words.’

OMNI:

You’ve said that dolphins also use ‘sonar beams’ to look at the internal state of one another’s body, or that of a human being, and that they can even gauge another’s emotional state that way. How does that work?

John C. Lilly:

They have a very high-frequency sonar that they can use to inspect something and look at its internal structure. Say you’re immersed in water and a sound wave hits your body. If there’s any gas in your body, it reflects back an incredible amount of sound. To the dolphin it would appear as a bright spot in the acoustic picture.

OMNI:

Can we ever really tune in to the dolphin’s “stereophonic” world view, or is it perhaps too alien to ours?

John C. Lilly:

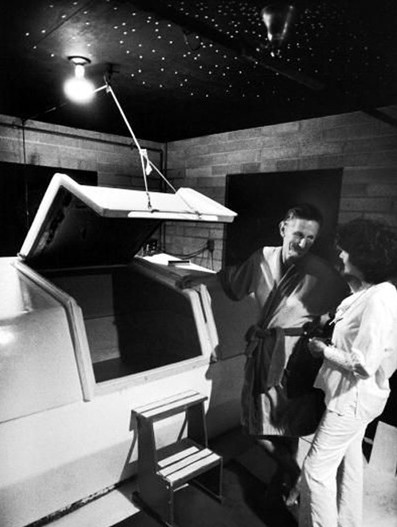

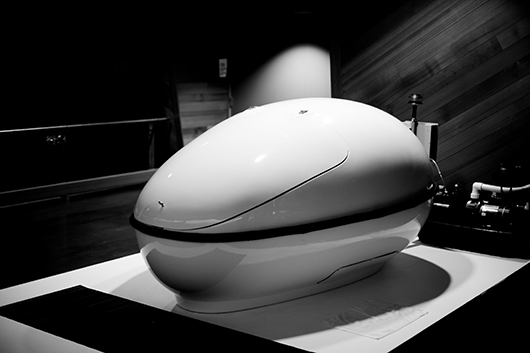

I want to. I just did a very primitive experiment — -a Saturday afternoon-type experiment — at Marine World I was floating in an isolation tank and had an underwater loudspeaker close to my head and an air microphone just above me. Both were connected through an amplifier to the dolphin tank so that they could hear me and I could hear them. I started playing with sound — whistling and clicking and making other noises that dolphins like. Suddenly I felt as if a lightning bolt had hit me on the head. We have all this on tape, and it’s just incredible. It was a dolphin whistle that went ssssshhheeeeeooooo in a falling frequency from about nine thousand to three thousand hertz in my hearing range. It started at the top of my head, expanding as the frequency dropped, and showing me the inside of my skull, and went right down through my body. The dolphin gave me a three-dimensional feeling of the inside of my skull, describing my body by a single sound!

I want to know what the dolphin experiences. I want to go back and repeat the experiment in stereo, instead of with a single loudspeaker. Since I’m not equipped like a dolphin, I’ve got to use an isolation tank, electronics, and all this nonsense to pretend I’m a dolphin.•