As has been said before, the problem with technology is one of distribution, not scarcity. Not a small challenge, of course.

We’ll need to work our way through what will likely be a wealthier if lopsided aggregate, but we all stand to gain in a more vital way: environmentally. The new tools, through choice and some fortuitousness, are almost all designed to make the world greener, something we desperately need to snake our way through the Anthropocene.

In Andrew McAfee’s latest post at his excellent Financial Times blog, he pivots off of Jesse Ausubel’s “The Return of Nature,” an essay which says that technological progress and information becoming the coin of the realm have led to a “dematerialization process” in America that is far kinder ecologically. Remember during the 1990s when everyone was freaking out about how runaway crime would doom society even as the problem had quietly (and mysteriously) begun a marked decline? Ausubel argues that a parallel situation is currently occurring with precious resources.

Two excerpts follow: 1) Ausubel asserts that a growing U.S. population hasn’t led to a spike in resource use, and 2) McAfee writes that the dematerialization process may explain some of the peculiarities of the economy.

______________________________

From Ausubel:

In addition to peak farmland and peak timber, America may also be experiencing peak use of many other resources. Back in the 1970s, it was thought that America’s growing appetite might exhaust Earth’s crust of just about every metal and mineral. But a surprising thing happened: even as our population kept growing, the intensity of use of the resources began to fall. For each new dollar in the economy, we used less copper and steel than we had used before — not just the relative but also the absolute use of nine basic commodities, flat or falling for about 20 years. By about 1990, Americans even began to use less plastic. America has started to dematerialize.

The reversal in use of some of the materials so surprised me that Iddo Wernick, Paul Waggoner, and I undertook a detailed study of the use of 100 commodities in the United States from 1900 to 2010. One hundred commodities span just about everything from arsenic and asbestos to water and zinc. The soaring use of many resources up to about 1970 makes it easy to understand why Americans started Earth Day that year. Of the 100 commodities, we found that 36 have peaked in absolute use, including the villainous arsenic and asbestos. Another 53 commodities have peaked relative to the size of the economy, though not yet absolutely. Most of them now seem poised to fall. They include not only cropland and nitrogen, but even electricity and water. Only 11 of the 100 commodities are still growing in both relative and absolute use in America. These include chickens, the winning form of meat. Several others are elemental vitamins, like the gallium and indium used to dope or alloy other bulk materials and make them smarter. …

Much dematerialization does not surprise us, when a single pocket-size smartphone replaces an alarm clock, flashlight, and various media players, along with all the CDs and DVDs.

But even Californians economizing on water in the midst of a drought may be surprised at what has happened to water withdrawals in America since 1970. Expert projections made in the 1970s showed rising water use to the year 2000, but what actually happened was a leveling off. While America added 80 million people –– the population of Turkey –– American water use stayed flat.•

______________________________

From McAfee:

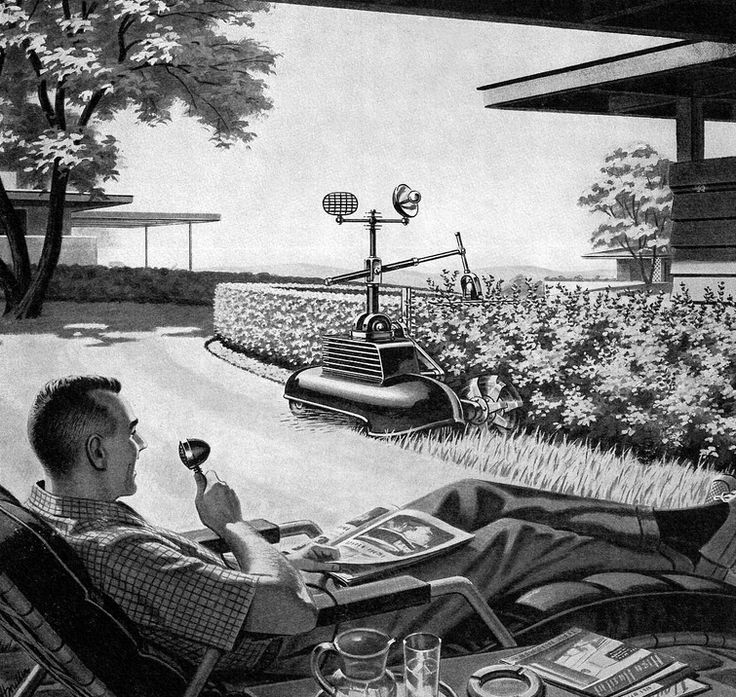

Software, sensors, data, autonomous machines and all the other digital tools of the second machine age allow us to use a lot fewer atoms throughout the economy. Precision agriculture enables great crop yields with much less water and fertiliser. Cutting-edge design software envisions buildings that are lighter and more energy efficient than any before. Robot-heavy warehouses can pack goods very tightly, and so be smaller. Autonomous cars, when (not if) they come, will mean fewer vehicles in total and fewer parking garages in cities. Drones will replace delivery trucks. And so on.

The pervasiveness of this process, which Mr Ausubel labels “dematerialisation,” might well be part of the reason that business investment has been so sluggish even in the US, where profits and overall growth have been relatively robust. Why build a new factory, after all, if a few new computer-controlled machine tools and some scheduling software will allow you to boost output enough from existing ones? And why build a new data centre to run that software when you can just put it all in the cloud?•