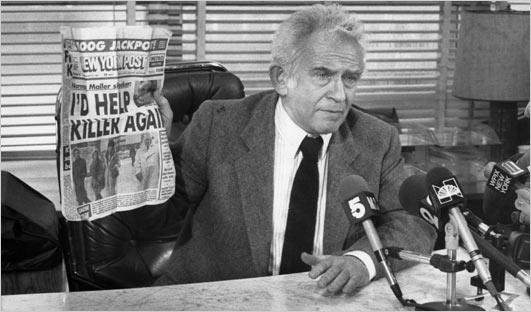

In posting a piece of Norman Mailer’s 1956 letter to the Democrats, urging party members to draft Ernest Hemingway for their Presidential ticket, I made passing reference to Jack Henry Abbott, the longtime convict and fledgling writer Mailer helped spring in 1981 to disastrous results. Abbott later died in prison, a suicide, in 2002. From his Los Angeles Times obituary, penned by Myrna Oliver:

In 1977, when Abbott learned that Mailer was writing the book The Executioner’s Song about death row inmate Gary Gilmore, he wrote the author, offering to advise him on how imprisonment affects men.

Mailer, later calling Abbott’s letters “as good as any convict’s prose that I had read since Eldridge Cleaver,” maintained a prolific correspondence with the inmate from 1978 to 1981.

In 1980, he had excerpts printed in the New York Review of Books, prodding Random House to suggest the book, which was published in 1981.

Mailer further went to bat for Abbott with the parole board, and in June 1981 succeeded in getting him released to a halfway house in New York’s Bowery.

The author bought him a $500 suit and a pair of good shoes, hired him as his $150-a-week researcher and introduced him to other influential people, including the late author Jerzy Kosinski.

Abbott the jailhouse writer quickly became a celebrity, interviewed on Good Morning America and other programs and featured in People magazine.

Within six weeks of his release from prison, glowing in the attention from his just-published book, he went to New York’s Binibon 24-hour restaurant with a girl on each arm, and got into an argument with the actor-waiter Richard Adan over using an employees’ restroom. Taking the fight outside, Abbott stabbed the waiter to death and fled.

The Sunday New York Times had just hit the street with a review of In the Belly of the Beast, describing the book as “awesome, brilliant, perversely ingenuous; its impact is indelible, and as an articulation of penal nightmare it is completely compelling.”

The fugitive Abbott was captured two months after the stabbing, convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 15 years to life. He was next due for a parole hearing in June 2003.

His book was adapted into an edgy play of the same title first by Adrian Hall at Trinity Square Playhouse in Rhode Island and then re-adapted by director Robert Woodruff for the Taper Forum in 1984. The Los Angeles production was based not only on Abbott’s letters but on transcripts from his manslaughter trial.

One Times reviewer, when the play opened, wrote: ‘The dramatization is a gut-wrenching indictment of far more than our penal system….It gives us Abbott, unadorned, in his own words, which is enough. He’s a devilishly articulate analyst of the system that has him by the throat. His perceptions are both astonishing and on the mark.’

In 1990, after a bizarre civil trial in which Abbott represented himself, a jury awarded Adan’s widow more than $7.5 million in damages for the wrongful death.

“I’ve become a writer,” Abbott told jurors during the 1990 civil trial, inquiring of each if he had read his book. “As good as any other writer in this country, or even in Europe. This was something told to me, and I was encouraged to write. It was told to me by some of the top publishers and editors in this country.”

But those once-fawning supporters changed their minds after Abbott stabbed a man, abusing the freedom they had helped him win. Mailer’s friend Scott Meredith said, “Norman and I are stunned and distressed. I guess there’s some residual regret on everyone’s part.”

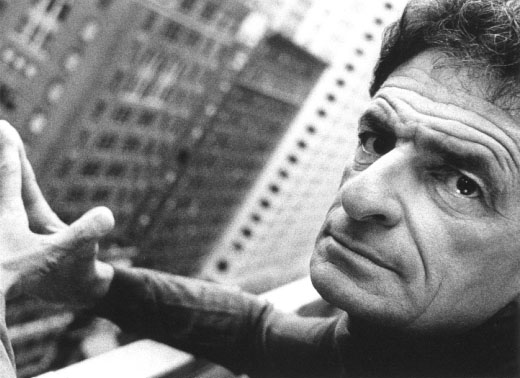

Kosinski was so remorseful that many said the episode contributed to his subsequent suicide. “Both Mailer and I believe in the purgatory power of art,” he mourned. “We pretended he [Abbott] had always been a writer. It was a fraud. It was like the ’60s, when we embraced the Black Panthers in that moment of radical chic without understanding their experience.

“I blame myself again for becoming part of radical chic,” he said. “I went to welcome a writer, to celebrate his intellectual birth. But I should have been welcoming a just-freed prisoner, a man from another planet.”•