Jean-Martin Charcot believed there was an underlying problem. In the big picture, he was right.

The 19th-century physician, considered the “father of neurology,” was pivotal in the understanding of ALS, Parkinson’s and other physical ailments, but it was his focus on neuroses that probably had the greatest impact on the world, through his own efforts and by those of his students.

In James Strachey’s introduction to a 1989 edition of Civilization and Its Discontents, he wrote:

Before his marriage, from October 1885 to February 1886, Freud worked in Paris with the celebrated neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who impressed Freud with his bold advocacy of hypnosis as an instrument for healing medical disorders, and no less bold championship of the thesis (then quite unfashionable) that hysteria is an ailment to which men are susceptible no less than women. Charcot, an unrivaled observer, stimulated Freud’s growing interest in the theoretical and therapeutic aspects of mental healing. Nervous ailments became Freud’s specialty, and in the 1890s, as he told a friend, psychology became his tyrant. During these years he founded the psychoanalytic theory of mind.

It’s easy to look askance at Charcot’s dubious reliance on hypnosis (even he eventually thought he overdid it) or Freud’s promotion of cocaine, but they were at that point essentially working in darkness, in possession of a few clues and searching for methods.

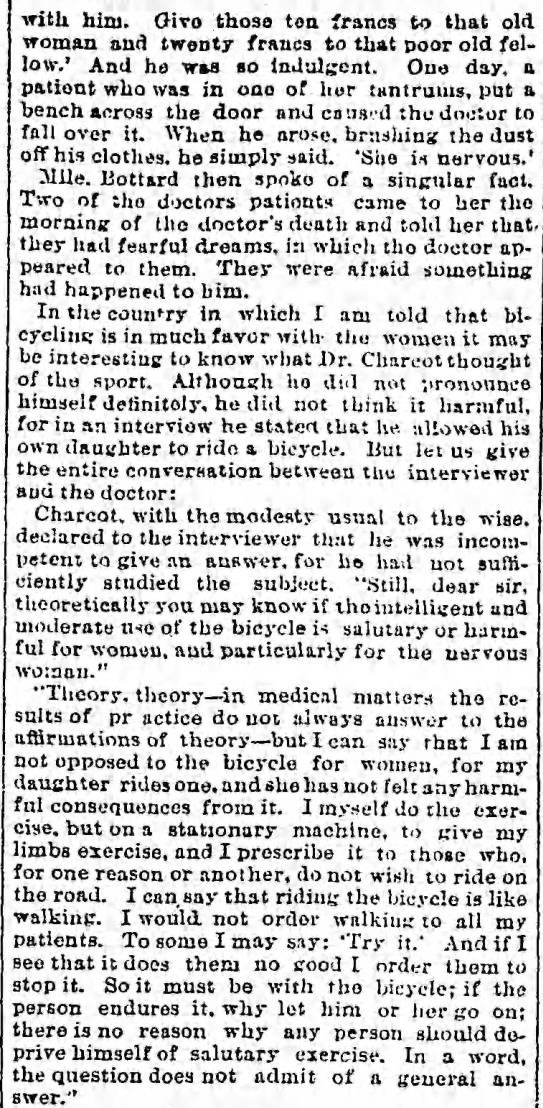

Charcot’s death was recorded in a September 10, 1893 article by Emma Bullet, Paris Correspondent of the Brooklyn Eagle. It includes a piece from an odd interview in which the doctor was asked if bicycling (which had only recently boomed in popularity) was healthy or injurious.