Few academics sweep as widely across the past or rankle as much in the present as Jared Diamond, the UCLA professor most famous (and infamous) for Guns, Germs and Steel, a book that elides superiority–and often volition–from the history of some humans conquering others. It’s a tricky premise to prove if you apply it to the present: More-developed countries have better weapons than some other states, but it still requires will to use them. Of course, Diamond’s views are more complex than that black-and-white picture. Two excerpts follow from Oliver Burkeman’s very good new Guardian article about the scholar.

_______________________________

In person, Diamond is a fastidiously courteous 77-year-old with a Quaker-style beard sans moustache, and archaic New England vowels: “often” becomes “orphan,” “area” becomes “eerier.” There’s no computer: despite his children’s best efforts, he admits he’s never learned to use one.

Diamond’s first big hit, The Third Chimpanzee (1992), which won a Royal Society prize, has just been reissued in an adaptation for younger readers. Like the others, it starts with a mystery. By some measures, humans share more than 97% of our DNA with chimpanzees – by any commonsense classification, we are another kind of chimpanzee – and for millions of years our achievements hardly distinguished us from chimps, either. “If some creature had come from outer space 150,000 years ago, humans probably wouldn’t figure on their list of the five most interesting species on Earth,” he says. Then, within the last 1% of our evolutionary history, we became exceptional, developing tools and artwork and literature, dominating the planet, and now perhaps on course to destroy it. What changed, Diamond argues, was a seemingly minor set of mutations in our larynxes, permitting control over spoken sounds, and thus spoken language; spoken language permitted much of the rest.

_______________________________

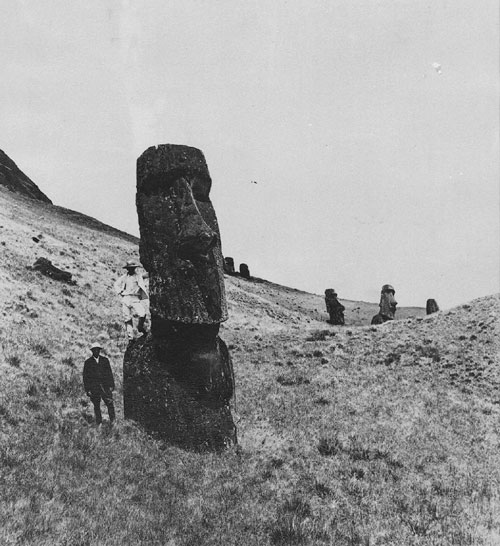

Geography sometimes plays a huge role; sometimes none at all. Diamond’s most vivid illustration of the latter is the former practice, in two New Guinean tribes, of strangling the widows of deceased men, usually with the widows’ consent. Other nearby tribes that have developed in the same landscape don’t do it, so a geographical argument can’t work. On the other hand: “If you ask why the Inuit, living above the Arctic Circle, wear clothes, while New Guineans often don’t, I would say culture makes a negligible contribution. I would encourage anyone who disagrees to try standing around in Greenland in January without clothes.” And human choices really matter: once the Spanish encountered the Incas, Diamond argues, the Spanish were always going to win the fight, but that doesn’t mean brutal genocide was inevitable. “Colonising peoples had massive superiority, but they had choices in how they were going to treat the people over whom they had massive superiority.”

It is clear that behind these disputes, is a more general distrust among academics of the “big-picture” approach Diamond has made his own.•