Novelists, like dictators, have long reigns. It is remarkable to think of Nabokov’s first book, a collection of love poems, appearing in his native Russia in 1914. Soon after, he and his family were forced to flee as a result of the Bolshevik uprising and the civil war. He took a degree at Cambridge and then settled in the émigré colony in Berlin. He wrote nine novels in Russian, beginning with Mary, in 1926, and including Glory, The Defense, and Laughter in the Dark. He had a certain reputation and a fully developed gift when he left for America in 1940 to lecture at Stanford. The war burst behind him.

Though his first novel written in English, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, in 1941, went almost unnoticed, and his next, Bend Sinister, made minor ripples, the stunning Speak, Memory, an autobiography of his lost youth, attracted respectful attention. It was during the last part of 10 years at Cornell that he cruised the American West during the summers in a 1952 Buick, looking for butterflies, his wife driving and Nabokov beside her making notes as they journeyed through Wyoming, Utah, Arizona, the motels, the drugstores, the small towns. The result was Lolita, which at first was rejected everywhere, like many classics, and had to be published by the Olympia Press in Paris (Nabokov later quarreled with and abandoned his publisher, Maurice Girodias). A tremendous success and later a film directed by Stanley Kubrick, the book made the writer famous. Nabokov coquettishly demurs. “I am not a famous writer,” he says, “Lolita was a famous little girl. You know what it is to be a famous writer in Montreux? An American woman comes up on the street and cries out, ‘Mr. Malamud! I’d know you anywhere.’ ”

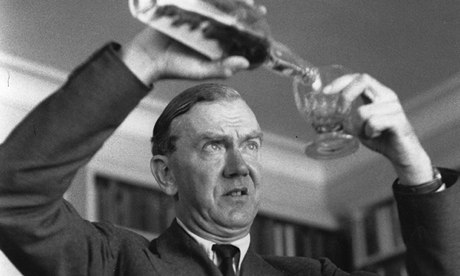

He is a man of celebrated prejudices. He abhors student activists, hippies, confessions, heart-to-heart talks. He never gives autographs. On his list of detested writers are some of the most brilliant who have ever lived: Cervantes, Dostoevsky, Faulkner and Henry James. His opinions are probably the most conservative, among important writers, of any since Evelyn Waugh’s. “You will die in dreadful pain and complete isolation,” his fellow exile, the Nobel Prize winner Ivan Bunin, told him. Far from pain these days and beyond isolation, Nabokov is frequently mentioned for that same award. “After all, you’re the secret pride of Russia,” he has written of someone unmistakably like himself. He is far from being cold or uncaring. Outraged at the arrest last year of the writer Maramzin, he sent this as yet unpublished cable to the Soviet writers’ union: “Am appalled to learn that yet another writer martyred just for being a writer. Maramzin’s immediate release indispensable to prevent an atrocious new crime.” The answer was silence.

Last year Nabokov published Look at the Harlequins!, his 37th book. It is the chronicle of a Russian émigré writer named Vadim Vadimych whose life, though he had four devastating wives, has many aspects that fascinate by their clear similarity to the life of Vladimir Vladimirovich. The typical Nabokovian fare is here in abundance, clever games of words, sly jokes, lofty knowledge, all as written by a “scornful and austere author, whose homework in Paris had never received its due.” It is probably one of the final steps toward a goal that so many lesser writers have striven to achieve: Nabokov has joined the current of history not by rushing to take part in political actions or appearing in the news but by quietly working for decades, a lifetime, until his voice seems as loud as the detested Stalin’s, almost as loud as the lies. Deprived of his own land, of his language, he has conquered something greater. As his aunt in Harlequins! told young Vadim, “Play! Invent the world! Invent reality!” Nabokov has done that. He has won.

“I get up at 6 o’clock,” he says. He dabs at his eyes. “I work until 9. Then we have breakfast together. Then I take a bath. Perhaps an hour’s work afterward. A walk, and then a delicious siesta for about two-and-a-half hours. And then three hours of work in the afternoon. In the summer we hunt butterflies.” They have a cook who comes to their apartment, or Véra does the cooking. “We do not attach too much importance to food or wine.” His favorite dish is bacon and eggs. They see no movies. They own no TV.

They have very few friends in Montreux, he admits. They prefer it that way. They never entertain. He doesn’t need friends who read books; rather, he likes bright people, “people who understand jokes.” Véra doesn’t laugh, he says resignedly. “She is married to one of the great clowns of all time, but she never laughs.”

The light is fading, there is no one else in the room or the room beyond. The hotel has many mirrors, some of them on doors, so it is like a house of illusion, part vision, part reflection, and rich with dreams.•