It’s only possible to guess from afar, but I’d wager that the diminution of neo-Nazi trolls and bots on Twitter in the post-election period isn’t largely due to tweaks made by Jack Dorsey & co., but has rather come about because those deployed to disrupt the election are no longer receiving checks from the Kremlin and god knows where else.

While the tweetstorm shitstorm has abated to a degree, we won’t know until the next election season if that rough beast is just waiting to be reborn. And things must be different next time because the tool was used like a weapon in 2016, bludgeoning democracy and decency.

The company isn’t in an easy position when it comes to the Tweeter-in-Chief, who uses the platform to slander, something that might not be as tolerated from those with lesser titles.

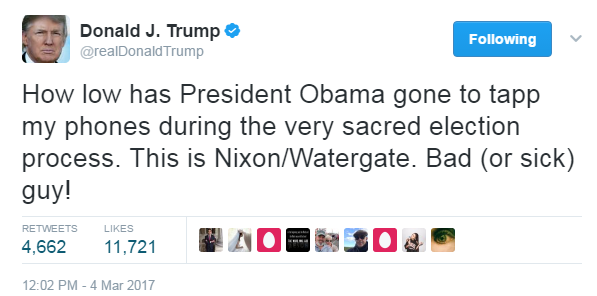

When Dorsey asserts in a smart Backchannel Q&A conducted by Steven Levy that Trump’s current tweets are “consistent with his tweets back in 2011-2012,” I have to assume he’s referring to form and not content, since the pathological liar now regularly contradicts his earlier criticisms of President Obama. People have fun retweeting his old comments to point out the hypocrisy, which I suppose is useful, or at least entertaining, but we may be entertaining ourselves to death.

One thing that’s not consistent with 2011-2012 is that Trump is now President and his 140-character discharges can lead to international incidents, even wars.

An excerpt in which Dorsey has clearly bought into the “forgotten Americans” narrative, which isn’t exactly Silicon Valley’s biggest problem:

Question:

Lately, a lot of people have been alleging that social media, including Twitter, has degraded the quality of public discourse. What do you think?

Jack Dorsey:

You can have conversation that’s distracting and you can have conversation that is focusing. I don’t think it’s a matter of the tool — it’s how people use the tool. Could we encourage better usage of Twitter through changing the product? Absolutely. We are always going to be looking for opportunities to make it easier, but also to show what matters faster. We moved from a completely time-ordered, reverse-chronological timeline to actually bubbling up what you should be seeing and what matters according to our understanding of what you’re interested in—and potentially showing the other side of what you’re interested in, as well. One of the values Twitter espouses is that it can show every side of a debate. I get the New York Times and I follow Fox, too, because I just want to challenge what I’m seeing. And that’s awesome. Whether you choose to dive into it or not is really up to you. We’re not going to force that on people.

Question:

But do you think Silicon Valley has worsened the divide?

Jack Dorsey:

It’s not just technology companies that are out of touch with a big part of the country and the world. I think it’s all of us. I think this city is out of touch with Missouri, where I’m from, and other people in areas like that. It is our responsibility to help bridge some of those gaps, because we’re building tools that people are using on a daily basis to connect with each other and to see the world. If we’re only fulfilling their bias, then we’re doing the wrong thing. We feel that burden and we want to help fix it. And the only way we can do that is by talking with people. So we go out of our way to listen and to have real conversations, not just seeing what people are saying on Twitter but actually bringing people in and interviewing them and talking about what they like and what they don’t like and what they are experiencing. The question I ask of anyone I meet who uses Twitter is: How do you use it, and why?•