A passage from “Murder Machines,” Hunter Oatman-Stanford’s Collectors Weekly article which recalls American streets before Henry Ford’s blasted contraptions became popular:

“Though various automobiles powered by steam, gas, and electricity were produced in the late 19th century, only a handful of these cars actually made it onto the roads due to high costs and unreliable technologies. That changed in 1908, when Ford’s famous Model T standardized manufacturing methods and allowed for true mass production, making the car affordable to those without extreme wealth. By 1915, the number of registered motor vehicles was in the millions.

Within a decade, the number of car collisions and fatalities skyrocketed. In the first four years after World War I, more Americans died in auto accidents than had been killed during battle in Europe, but our legal system wasn’t catching on. The negative effects of this unprecedented shift in transportation were especially felt in urban areas, where road space was limited and pedestrian habits were powerfully ingrained.

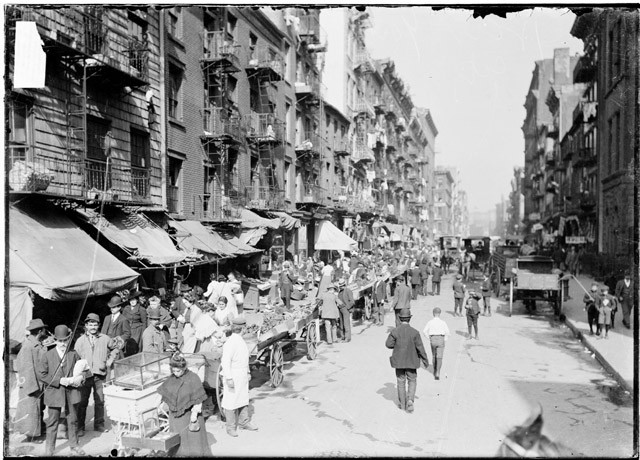

For those of us who grew up with cars, it’s difficult to conceptualize American streets before automobiles were everywhere. ‘Imagine a busy corridor in an airport, or a crowded city park, where everybody’s moving around, and everybody’s got business to do,’ says Norton. ‘Pedestrians favored the sidewalk because that was cleaner and you were less likely to have a vehicle bump against you, but pedestrians also went anywhere they wanted in the street, and there were no crosswalks and very few signs. It was a real free-for-all.’

Roads were seen as a public space, which all citizens had an equal right to, even children at play. ‘Common law tended to pin responsibility on the person operating the heavier or more dangerous vehicle,’ says Norton, ‘so there was a bias in favor of the pedestrian.’ Since people on foot ruled the road, collisions weren’t a major issue: Streetcars and horse-drawn carriages yielded right of way to pedestrians and slowed to a human pace. The fastest traffic went around 10 to 12 miles per hour, and few vehicles even had the capacity to reach higher speeds.

In rural areas, the car was generally welcomed as an antidote to extreme isolation, but in cities with dense neighborhoods and many alternate methods of transit, most viewed private vehicles as an unnecessary luxury. ‘The most popular term of derision for a motorist was a ‘joyrider,’ and that was originally directed at chauffeurs,’ says Norton. ‘Most of the earliest cars had professional drivers who would drop their passengers somewhere, and were expected to pick them up again later. But in the meantime, they could drive around, and they got this reputation for speeding around wildly, so they were called joyriders.'”