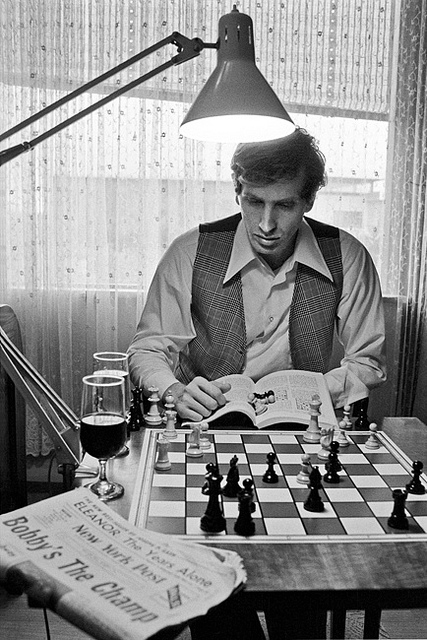

Speaking of chess prodigies who declined young, Bobby Fischer, who was profiled in Life by Brad Darrach in 1971 prior to his Cold War showdown with champion Boris Spassky, was the subject of the same writer for sister publication People in 1974, two years after dispatching of his Soviet opponent and becoming one of the most famous people on Earth. Darrach wrote of Fischer as a man who’d shaken off the world’s embrace, who had briefly found God–one of them, anyhow–and had entered into an exile from the game. What the piece couldn’t have predicted is that he would never really play another meaningful match. The opening of “The Secret Life of Bobby Fischer“:

Whatever happened to Bobby Fischer? Six weeks after winning the world chess championship on Sept. 1, 1972, he abruptly vanished without a trace into the brown haze of Greater Los Angeles. Rumors flew, but the truth was weirder than the rumors.

At the pinnacle of chess success, Bobby abandoned the game that had made him famous and took up residence in a closed California community of religious extremists. With rare exceptions, the world outside has not seen or heard of him for more than 16 months. Reporters who tried to track him down were turned back by the private police force that patrols the church property in Pasadena.

On the day he finished off his great Russian opponent, Boris Spassky, in Iceland, Bobby had realized the first of his three main ambitions. The second, he said, was ‘to make chess a major sport in the United States.’ The third was to be ‘the first chess millionaire.’ As history’s first purely intellectual superstar, Bobby was offered record deals, TV specials, book contracts, product endorsements. ‘He could make $10 million in the next two, three years,’ his lawyer said after Bobby’s victory at Reykjavik. And to promote chess, Bobby promised to put his title on the line ‘at least twice a year, maybe more.’ Millions of chess amateurs enthused at the prospect of a Fischer era of storm, stress and magnificent competition.

But it didn’t happen quite like that. After curtly declining New York Mayor Lindsay’s offer of a ticker-tape parade (“I don’t believe in hero worship”), Bobby made impulsive appearances on the Bob Hope and Johnny Carson shows—and then was swallowed up by the Worldwide Church of God, a fundamentalist sect founded in 1934 by a former adman named Herbert W. Armstrong. Well advertised on radio and television by Armstrong’s hellfire preaching—and more recently by the charm-drenched sermons of Garner Ted Armstrong, the founder’s son—the church now claims 85,000 members. They celebrate the sabbath on Saturday and observe the dietary laws of the Old Testament—no pork, no shellfish. Smoking, divorce and cheek-to-cheek dancing are forbidden. Necking is the worst kind of sin. Tithing is mandatory—the church’s annual income probably exceeds $50 million. Church leaders live palatially and gad about the world in three executive jets provided by the faithful. Recently, however, scandals and schisms have shaken the flock.

Bobby Fischer, the child of a Jewish mother and a Gentile father, first tuned in on the elder Armstrong while still in his late teens. Lonely and despairing after he muffed his chance to become world champion at 19—Bobby found strength in the church’s teachings and has adhered to them closely ever since. He turned to the church in the crisis he faced after Reykjavik. Verging on nervous exhaustion after his two-month battle with Spassky and the match organizers, Bobby decided that the last thing he wanted after his triumph was the world that lay at his feet. In the large and outwardly peaceful community that surrounds the Armstrong headquarters, he saw a safe setting where he could unsnarl his nerves and find the normal life that he had sacrificed to competition and monomania.

The church welcomed him. Though Bobby is not a full church member—he is listed as a ‘coworker’—he offered Armstrong a double tithe (20%) of his $156,250 winnings. ‘Ah, my boy, that’s just as God would have it!’ Armstrong replied, and passed the word that Bobby was to be given VIP treatment. A pleasant three-bedroom apartment in a church-owned development was made available. So were the gymnasium, squash courts and swimming pool of the church’s Ambassador College. Leaders of the Armstrong organization were told to make sure that Bobby had plenty of dinner invitations. “The word went out,” says a church member, “that Bobby should never be left alone, or allowed to feel neglected.”

To make doubly sure, the church assigned a friendly weightlifter in the phys. ed. department as Bobby’s personal recreation director. The two of them played paddle tennis almost every day, and Bobby worked out with weights to build up his arms and torso.

Not long after he arrived in Pasadena, the 31-year-old Bobby confessed to a high church official that he wanted to meet some girls. There is a rigid rule against dating between church members and nonmembers like Bobby, but the official allowed that in Bobby’s case the rule would be suspended. What sort of girls did he like? Bobby said that he liked “vivacious” girls with “big breasts.” A suitable girl was discovered and Bobby began to date her frequently, taking the weightlifter and his wife along as chaperones.•