Following up on yesterday’s post about America’s foundering infrastructure, here’s a section from a New Republic piece by Tom Vanderbilt, who, in this segment, directs his ire at NYC’s woeful highways and information superhighway, overwhelmed by population density, poor planning and lack of resources. I could say that the city’s success has come with a heavy price, drawing more transplants and tourists than it could handle, except that I’ve live here my whole life and the infrastructure has always been an ordeal, in good times as well as bad.

Vanderbilt riffs off of the American Society of Civil Engineers’ harsh grades for our bridges and tunnels and Henry Petroski’s new book, The Road Taken. The excerpt:

As an interest group, we might expect a certain amount of grade inflation—or, in this case, deflation—from the ASCE; proclaiming the country’s infrastructure to be in decent working order is not likely, after all, to generate much work for engineers. But it does not take a vested interest to sense that America, whose roads and rails were once the envy of the developed world, has somehow gone astray.

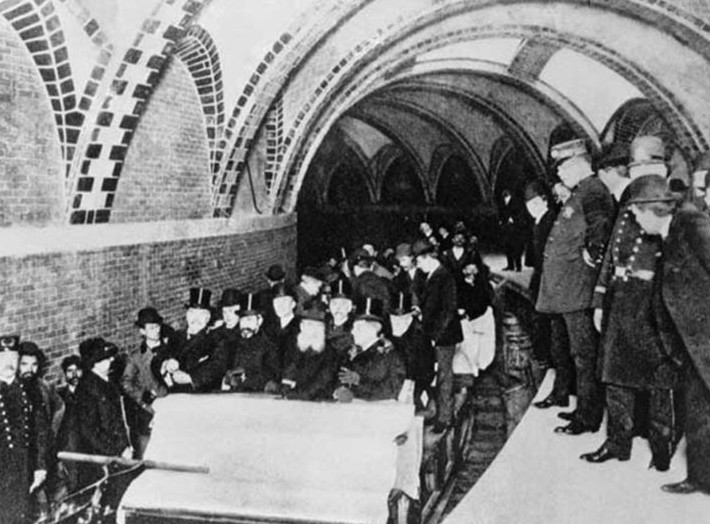

To take New York City—where I live and where Petroski grew up—as an example, despite being constantly told I live in the center of the world, when it comes to infrastructure, I am constantly wishing I were elsewhere. When the subway comes screeching along, tinnitus on braking metal, I long for the silent rubber tires used by trains in Mexico City or Montreal. When I salmon against the crushing stream of pedestrian and bicycle traffic on the stingy walkway of the Brooklyn Bridge, I long for Brisbane’s capacious, car-free Kurilpa Bridge. Flying into any Gotham airport, the convenient, legible urban transport links one finds in Amsterdam or Geneva are absent. There are cities in Kansas, thanks to Google Fiber, that currently have better bandwidth than the nation’s media capital. Growing up in Brooklyn, many decades ago, Petroski notes that he and his childhood friends would occasionally go down the hill, from Park Slope, until they ran into the Gowanus Canal, “stagnant and odorous.” In 2016, the canal is still stagnant and odorous, an EPA Superfund site, even as glassy luxury condos rise on its fetid banks.

“America,” argues Petroski, gleaning a hoary image from Robert Frost, “is now at a fork in the road representing choices that must be made regarding the nation’s infrastructure.”•