Isabell Hülsen of Spiegel conducted an excellent Q&A with Henry Blodget, that mixed blessing, about digital and traditional media landscapes. The subject reinvented himself with Business Insider, returning to his journalistic roots after being charged with securities fraud and banned for life from the sector.

Blodget is relatively sanguine about the future of online journalism, though he acknowledges those seeking success will have to skillfully balance serious reportage and cat memes. There’s no discussion about the many publications basing a good chunk of their futures on video, which seems likely another bubble that could pop once advertisers take a closer look.

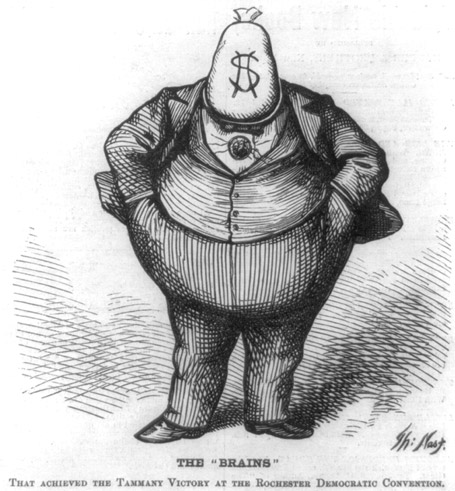

In one exchange, Blodget says this: “In the new world of digital, there are no must-read publications any more.” That reminds me of something Jake Silverstein, the excellent editor of the New York Times Magazine, said not that long ago. He asserted his ambition was to make his publication indispensable, one you had to read if you wanted to sound informed at a party. That simply doesn’t exist anymore–the party’s over. That reality has probably made our world better in the big picture, though something has been lost with what’s been gained.

An excerpt:

Spiegel:

The power of digital publishing lies in the ability to know what readers like, which stories they actually read and which ones they don’t — and to give them more of what they like. This creates the danger of a filter bubble.

Henry Blodget:

What do you mean by filter bubble?

Spiegel:

Reading becomes a sort of self-optimization and self-reference, the only things that get through to me from the flood of information are those which I want to consume and which I like. My Facebook and Twitter feeds filter what fits into my conception of the world.

Henry Blodget:

I don’t think that is actually what is happening. In fact, we have more information than ever before, and it is harder than ever to avoid actually seeing what the other side is saying. Yes, we focus on publications that we feel speak to us, but that is exactly the same way it was 20 or 100 years ago. In the US, two million people have subscribed to the New York Times and many more millions think theNew York Times is a terrible, liberal paper they would never read. We can, of course, choose to put ourselves in a bubble of only people who agree with us, but in the digital world there are many more ways of saying “Hey, here is something you might want to consider.”

Spiegel:

How compatible is the idea of offering readers more and more of what they like with the role of journalists in a democratic society: to publish information that is relevant to our social coexistence but not necessarily read by millions of people; to investigate and uncover scandals and cases of wrongdoing?

Henry Blodget:

Before the internet, big publications were like hydrants in the desert. There were relatively few of them, we needed each one of them tremendously and they had control over what was delivered. Now they are like little streams flowing into a massive ocean. An example: Before the internet, a journalist would write an article about a company that the company felt was unfair and missed a point. All they could do was write a letter to the editor and wait, and maybe a week later it would be printed, or not. Now, they can go to medium.com and immediately publish a long rebuttal, saying the journalist forgot this and did not consider that, the analyst is wrong here. Everybody pulls that immediately into the debate. So it is a much more democratic field for ideas.•