Noted yesterday the passing of Hans Berliner, the chess and computer genius who combined his passions to great effect. Before reducing kings and pawns to zeros and ones, he led the way in creating the first game-champion computer, a backgammon behemoth which beat the best carbon competitors 38 years ago, though it did receive some lucky rolls in the process. The opening of “Gammonoid the Conqueror,” Henry Allen’s Washington Post 1979 report about the rise of the machine at the site of a Monte Carlo tournament:

Programming a computer to beat the world back-gammon champion was mere science. It was the Italians who were the miracle. Luigi Villa, nearly unheard of in big-time back-gammon (which gets bigger all the time) won the world professional championship last weekend in Monte Carlo, fighting off a field which included the cream of the world-class players — Paul Magriel, Barclay Cooke, Joe Dwek, Jim Pasko and so on. The match with the computer was just an after-thought, a publicity stunt. Villa agreed to sit at a board at the Winter Sporting Club. Before a crowd of 200 people basking in the upholstered chairs, the champagne, the wonderful silliness of it all, he would play a single seven-point match for $5,000.

But of course. Backgammon has never had anything mechanical about it, none of chess’ terrible cerebral ether surrounding it. It’s been a drinker’s game, the thinking man’s darts, a game which is almost unplayable unless there’s a bet riding on it big enough to hurt if it’s lost. It’s a game of brass and intuition, the poker of board games.

He lost.

As a wire service report put it, in syntax nearly as elegant as the casino: “Villa’s disappointment was shared by several fellow Italians, who surrounded him in an indignant and gesticulating mass immediately afterwards and hurled insults at the machine.”

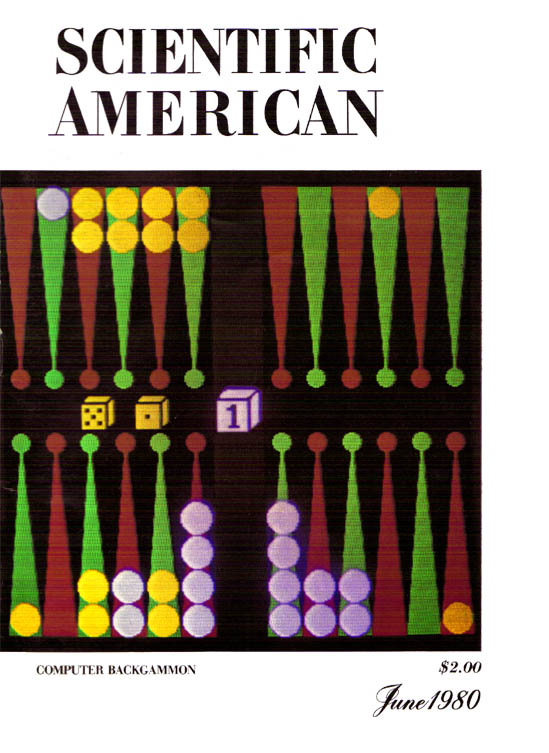

The computer, known as a “gammonoid” and semi-anthropomorphized as a 3 1/2-foot robot bearing TV screen and keyboard, won seven to one – roaring to a particularly nice finish when, behind, it rolled two double-sixes to clear its board before Villa could clear his.

“The machine was lucky,” he said. “The dice were not rolling for me tonight.” He was reported to have stamped his foot.

“We’d figured we had a 20 percent chance of winning,” said Carnegie-Mellon University computer science student Charles Leiserson yesterday. “I’d rate the program at advanced intermediate. I can beat it more than half the time but by Christmas it may be improved enough that I can’t.”

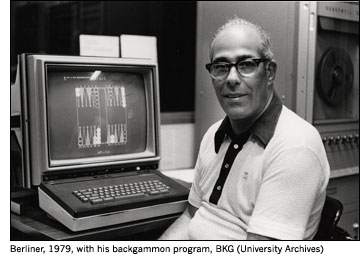

Leiserson is an associate of Dr. Hans Berliner, a research scientist at Carnegie-Mellon in Pittsburgh. Berliner, who was in Monte Carlo for the bout, has been working on his back-gammon machine for years, “writing programs, then tearing them up,” Leiserson recalled.

The program is made of about a million “bits” or basic pieces of computerized information. The problem in writing it has been that backgammon, unlike chess, another computer favorite, relies on the rolls of dice to determine the play.

Backgammon has a lot of luck in it, in other words. Also, Villa, from Milan, Itlay, was no doubt facing a computer for the first time.

Villa’s opponent wasn’t even in the room, or in Europe, for that matter. Rolls of the dice were flashed by satellite to a PDP 10 computer in Pittsburgh, which then sent back the move it had chosen according to its scanning of about a dozen “parameters” that Berliner has established through the years. Some of them are familiar to conventional backgammon players, such as pip count, or the number of men on the bar.

A run of seven points is not uncommon, either.

“Four years ago, when I won the world championship, I was behind 9 to zero before I won 25 to 24,” said Les Boyd, president of the International Backgammon Association.

Then again, Boyd said: “Seven to one? The machine beat him. Maybe 7 points isn’t a lot, but in the World Series, one pitch can win it or lose it, right?”

In Monte Carlo, former world champion Paul Magriel did the play-by-play commentary, effervescing: “Look at this play. I didn’t even consider this play . . . This is certainly not a human play. This machine is relentless. Oh, it’s aggressive. It’s a really courageous machine.”•