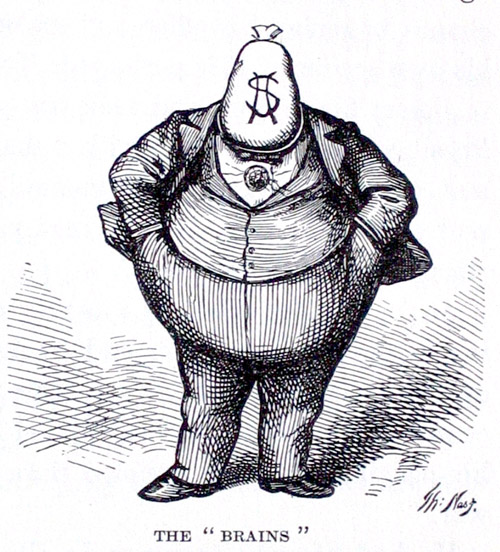

Months before the first 2011 Occupy protest in Zuccotti Park, economist Joseph Stiglitz was bemoaning the 1%, doggedly working to put a spotlight on wealth inequality and the rigged system that abets it. These days, he feels the discussion has evolved but there haven’t been any real material changes.

Gawker took a break from being yeesh! long enough to allow Hamilton Nolan to do his typically smart work, interviewing Stiglitz about how disparity can be mitigated. Simply put, he doesn’t believe fairness can be achieved through charitable donations but will require systemic changes. An excerpt:

Question:

Is there a red line level of inequality past which you think there will be some sort of tipping point?

Joseph Stiglitz:

We’re always gonna have some inequality. There is a small enough level of inequality that, while you might worry about it, it doesn’t have a corrosive effect. We’ve reached a level of inequality where it’s unambiguously clear to me and to most observers that it’s interfering with our economic performance. It’s having a corrosive effect on the way our democracy works. It’s having a corrosive effect on the way our society functions. So we’re in the bad regime. We’re facing very large costs.

The other question that you’re asking is, “Is there a tipping point, a dynamic where things get more and more unequal and increasingly hard to pull back?” I would say yes, and what that point is depends on a number of factors, including the political landscape. I believe a lot of inequality is a result of the policies we make. Those policies are a result of political processes. Political processes are affected by the rules that [govern] how money gets translated into politics. So if you have a political system like the US, where money talks more than in Europe, that is going to have a more corrosive effect—a lower tipping point. I try to be optimistic. I wouldn’t be working so hard if I believed we were over that tipping point. There’s some chance we are over it, but there’s some chance that we’re not. The fight right now is to make sure we don’t go further over it.

Question:

Is it possible to rein it in with our current campaign finance system?

Joseph Stiglitz:

It’s possible, and difficult. We’ve seen successes in the minimum wage campaign. We’ve seen successes in when the Republicans try to restrict voting rights in Pennsylvania, it backfired and people got so angry that they came out and voted. So every once in a while you see an outpouring of democratic forces.

Question:

Where would you set the income tax rates, if it was up to you?

Joseph Stiglitz:

The first order of business should be creating a fair tax system, so that we tax dividends and speculators at the same rate that we tax ordinary income.•