When you’re gambling large sums of money in a boom-or-bust business, the sky is always falling, and despite gigantic grosses, Hollywood has never looked more at its chandelier like a concussion-in-waiting. Today, technology can’t be controlled and global markets are now the dog pulling the leash. The cultural concerns go beyond film itself: If we have only blockbusters borne of comic books, what sort of ramifications does that have on the culture?

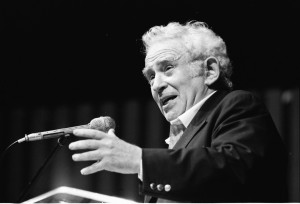

But those concerns are not unique to our time. The New York Review of Books just republished Gore Vidal’s epic two-part 1973 article, “The Ashes of Hollywood” (Pt. 1 + Pt. 2), which examined the effect Tinseltown’s so-called Golden Age had on the literature written by those weaned on it.

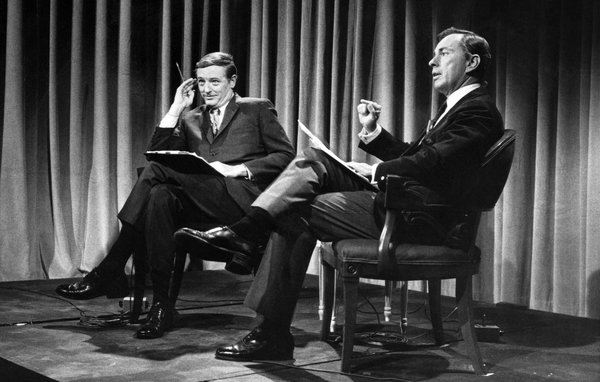

Vidal could not have foreseen parts of TV becoming so literate and personal as film grew into something behemoth and post-literate. Of course, Vidal probably would have had little kindness for contemporary television, either. He hated everything that wasn’t him or didn’t flatter him. The article’s opening:

“‘Shit has its own integrity.’ The Wise Hack at the Writers’ Table in the MGM commissary used regularly to affirm this axiom for the benefit of us alien integers from the world of Quality Lit. It was plain to him (if not to the front office) that since we had come to Hollywood only to make money, our pictures would entirely lack the one basic homely ingredient that spells boffo world-wide grosses. The Wise Hack was not far wrong. He knew that the sort of exuberant badness which so often achieves perfect popularity cannot be faked even though, as he was quick to admit, no one ever lost a penny underestimating the intelligence of the American public. He was cynical (so were we); yet he also truly believed that children in jeopardy always hooked an audience, that Lana Turner was convincing when she rejected the advances of Edmund Purdom in The Prodigal ‘because I’m a priestess of Baal,’ and he thought that Irving Thalberg was a genius of Leonardo proportion because he had made such tasteful ‘products’ as The Barretts of Wimpole Street and’ Marie Antoinette.

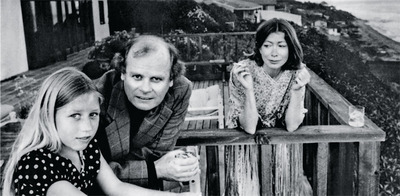

In my day at the Writers’ Table (mid-Fifties) television had shaken the industry and the shit-dispensers could now…well, flush their products into every home without having to worry about booking a theater. In desperation, the front office started hiring alien integers whose lack of reverence for the industry distressed the Wise Hack who daily lectured us as we sat at our long table eating the specialty of the studio, top-billed as the Louis B. Mayer Chicken Soup with Matzoh Balls (yes, invariably, the dumb starlet would ask, what do they do with the rest of the matzoh?). Christopher Isherwood and I sat on one side of the table; John O’Hara on the other. Aldous Huxley worked at home. Dorothy Parker drank at home.

The last time I saw her, Los Angeles had been on fire for three days. As I took a taxi from the studio, I asked the driver, ‘How’s the fire doing?’ ‘You mean,’ said the Hollywoodian, ‘the holocaust.’ The style, you see, must come as easily and naturally as that. I found Dorothy standing in front of her house, gazing at the smoky sky; in one hand she held a drink, in the other a comb which absently she was passing through her short straight hair. As I came toward her, she gave me a secret smile. ‘I am combing,’ she whispered, ‘Los Angeles out of my hair.’ But of course that was not possible. The ashes of Hollywood are still very much in our hair, as the ten bestsellers I have just read demonstrate.

The bad movies we made twenty years ago are now regarded in altogether too many circles as important aspects of what the new illiterates want to believe is the only significant art form of the twentieth century. An entire generation has been brought up to admire the product of that era. Like so many dinosaur droppings, the old Hollywood films have petrified into something rich, strange, numinous-golden. For any survivor of the Writers’ Table (alien or indigenous integer), it is astonishing to find young directors like Bertolucci, Bogdanovich, Truffaut reverently repeating or echoing or paying homage to the sort of kitsch we created first time around with a good deal of ‘help’ from our producers and practically none at all from the directors—if one may quickly set aside the myth of the director as auteur. Golden age movies were the work of producer(s) and writer(s). The director was given a finished shooting script with each shot clearly marked, and woe to him if he changed MED CLOSE SHOT to MED SHOT without permission from the front office, which each evening, in serried ranks, watched the day’s rushes with script in hand (‘We’ve got some good pages today,’ they would say; never good film). The director, as the Wise Hack liked to observe, is the brother-in-law.'”