The Daily Beast has reprinted Gay Talese’s 1970 Esquire article, “Charlie Manson’s Home on the Range,” which looks at living arrangements of the madman and his minions when they set up house on the desolate land outside of Los Angeles of blind, lonesome rancher George Spahn. An excerpt about when the iceman first cometh:

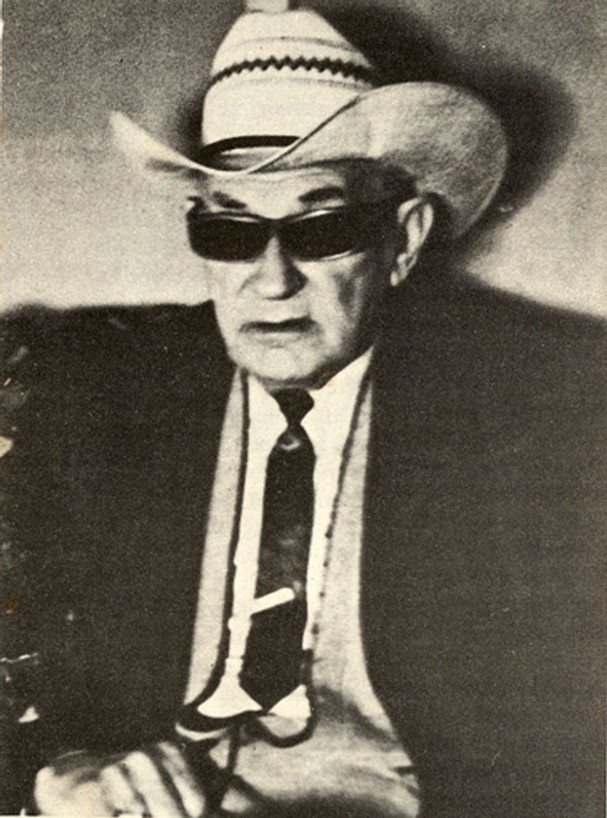

Then one day a school bus carrying hippies arrived at the ranch and parked in the woods, and young girls approached Spahn’s doorway, tapping lightly on the screen, and asked if they could stay for a few days. He was reluctant, but when they assured him that it would be only for a few days, adding that they had had automobile trouble, he acquiesced. The next morning Spahn became aware of the sound of weeds being clipped not far from his house, and he was told by one of the wranglers that the work was being done by a few long-haired girls and boys. Later, one of the girls offered to make the old man’s lunch, to clean out the shack, to wash the windows. She had a sweet, gentle voice, and she was obviously an educated and very considerate young lady. Spahn was pleased.

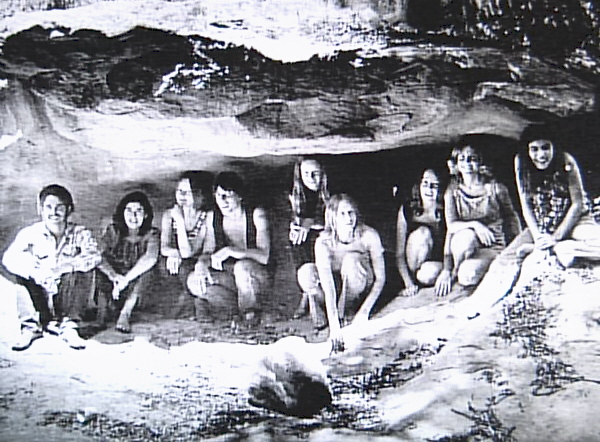

In the days that followed, extending into weeks and months, Spahn became familiar with the sounds of the other girls’ voices, equally gentle and eager to do whatever had to be done; he did not have to ask them for anything, they saw what had to be done, and they did it. Spahn also came to know the young man who seemed to be in charge of the group, another gentle voice who explained that he was a musician, a singer and poet, and that his name was Charlie Manson. Spahn liked Manson, too. Manson would visit his shack on quiet afternoons and talk for hours about deep philosophical questions, subjects that bewildered the old man but interested him, relieving the loneliness. Sometimes after Spahn had heard Manson walk out the door, and after he had sat in silence for a while, the old man might mutter something to himself— and Manson would reply. Manson seemed to breathe soundlessly, to walk with unbelievable silence over creaky floors. Spahn had heard the wranglers tell of how they would see Charlie Manson sitting quietly by himself in one part of the ranch, and then suddenly they would discover him somewhere else. He seemed to be here, there, everywhere, sitting under a tree softly strumming his guitar. The wranglers had described Manson as a rather small, dark-haired man in his middle 30s, and they could not understand the strong attraction that the six or eight women had for him. Obviously, they adored him. They made his clothes, sat at his feet while he ate, made love to him whenever he wished, did whatever he asked. He had asked that the girls look after the old man’s needs, and a few of them would sometimes spend the night in his shack, rising early to make his breakfast. During the day they would paint portraits of Spahn, using oil paint on small canvases that they had brought. Manson brought Spahn many presents, one of them being a large tapestry of a horse.

He also gave presents to Ruby Pearl—a camera, a silver serving set, tapestries—and once, when he said he was short of money, he sold her a $200 television set for $50. It was rare, however, that Manson admitted to needing money, although nobody on the ranch knew where he got the money that he had, having to speculate that he had been given it by his girls out of their checks from home, or had earned it from his music. Manson claimed to have written music for rock-and-roll recording artists, and sometimes he was visited at the ranch by members of the Beach Boys and also by Doris Day’s son, Terry Melcher. All sorts of new people had been visiting the ranch since Manson’s arrival, and one wrangler even claimed to have seen the pregnant movie actress Sharon Tate riding through the ranch one evening on a horse. But Spahn could not be sure.

Spahn could not be certain of anything after Manson had been there for a few months. Many new people, new sounds and elements, had intruded so quickly upon what had been familiar to the old blind man on the ranch that he could not distinguish the voices, the footsteps, the mannerisms as he once had; and without Ruby Pearl on the ranch each night, Spahn’s view of reality was largely through the eyes of the hippies or the wranglers, and he did not know which of the two groups was the more bizarre, harebrained, hallucinatory.•