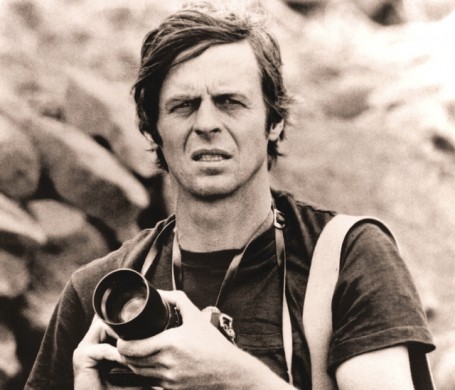

- George Plimpton seemed to have lost the will to live soon after I interviewed him in 2003. Two weeks later he was dead. It was unintentional, I swear.

- The best part of Plimpton’s journalism, from being an embed Bedouin on the set of Lawrence of Arabia to playing quarterback in a preseason game for the Detroit Lions, was that he realized the business sometimes served an important purpose, but the vast majority of it was a lark to have fun in between visits from the Time Inc. drink cart. I cant say I approve of his mixing fiction into his fact, but the lust for life was admirable. Perhaps being in close proximity to Robert F. Kennedy as he was assassinated–he helped wrest the gun from Sirhan Sirhan’s hand–gave him perspective that life and death is life and death, and everything else is not.

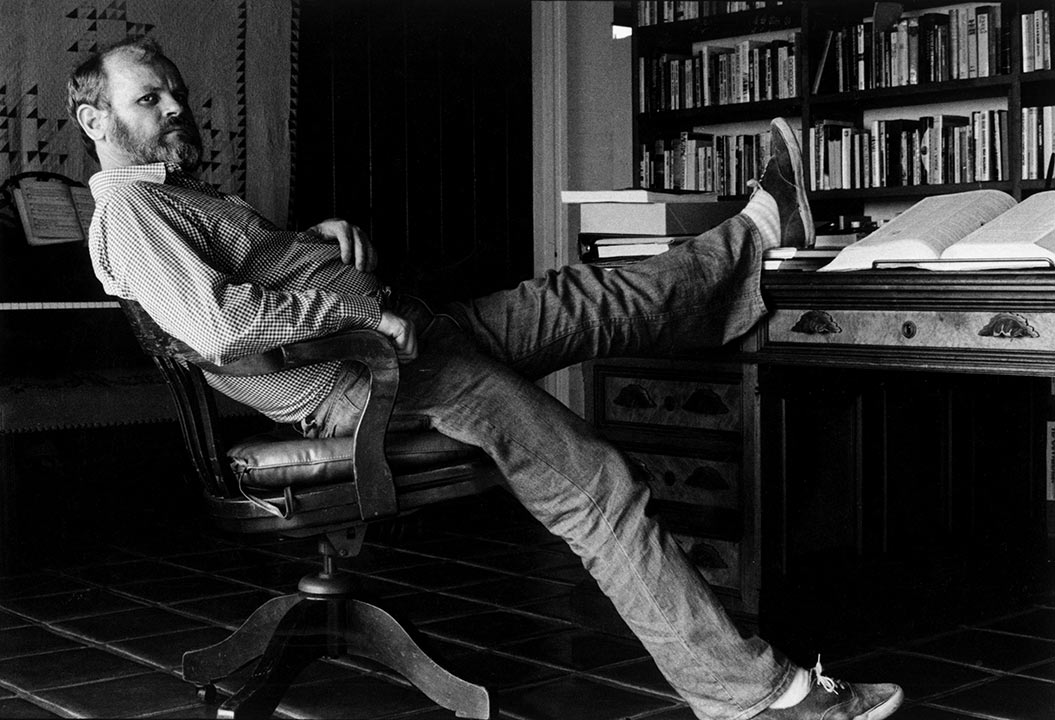

- Plimpton began writing for Sports Illustrated in the 1950s, one of the young literary lights recruited by editor Sid James to write for his publication in that era. Plimpton thrived, with the magazine nurturing his flair for participatory journalism. One who did less well was Kurt Vonnegut, whose first assignment was to write a full-length article about a spooked racehorse that jumped over a fence. Before grabbing his coat and exiting the offices to never return, he typed these words: “The horse jumped over the fucking fence.”

- I’m sure there was some great national prank after Plimpton’s Sidd Finch story on April Fools Day in 1985, but that was one of the last hurrahs of the pre-Information Age, a story that would unravel now on Twitter in minutes. We still get fooled a lot, but by nothing nearly so wonderful.

In a New York Review of Books piece about Plimpton’s sports journalism, Nathaniel Rich acknowledges that sometimes the writer dropped the ball, as he did in underplaying that racial hatred directed at Henry Aaron as the Atlanta slugger closed in on Babe Ruth’s home-run record, but his close proximity to the game often allowed him to digest small details about the games, including points about class, something not every patrician would appreciate. An excerpt:

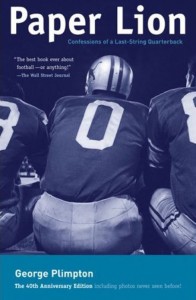

Sports memoirs, like humor collections, rarely outlive their authors, but Plimpton’s books have aged gracefully and even matured. Today they have the additional (and unintended) appeal of vivid history, bearing witness to a mythical era that, as Rick Reilly writes in his foreword to The Bogey Man, “historians classify as ‘Before Insurance Lawyers Ruined Everything.’” (Journalists might classify it as Before Fact-Checkers Ruined Everything.) Plimpton writes about baseball locker rooms “heavy with cigarette and cigar smoke,” star players humbled by their off-season jobs (Pro-Bowler Alex Karras fills jelly doughnuts), and teams that cheat by positioning a spy with binoculars on a roof near the opponent’s practice field. He is able to convince major league All-Stars to take part in his scheme by offering, to the players on the team that gets the most hits off him, a reward of $125, the equivalent today of about $1,000. (By comparison, the Detroit Tigers’ slugger Miguel Cabrera earned $19,000 per inning this season.) It was also an age in which the press was powerful enough to convince professional teams to grant full, unfettered access to a journalist. Today a writer for a major national magazine is lucky to be allowed more than one hour with the subject of a cover article. Plimpton spent a full month living in a dormitory with the Lions.

As enjoyable as it is to read about Plimpton being treated roughly by professional gladiators in front of large crowds, the participatory approach also has its journalistic benefits. He understood that within every professional athlete is an amateur who, through some combination of born talent and luck, is surprised to find himself elevated to divine status. As a writer who, after the success of Paper Lion, was a bigger celebrity than most of his subjects, Plimpton had a special sensitivity to the hidden vulnerabilities of giants.

The weigh-in ceremony before Cassius Clay’s first championship fight against Sonny Liston is best remembered for Clay’s rumbling taunts, but Plimpton notes that Clay’s pulse was taken at 180; the doctor concluded that he was “scared to death.” We learn that Roger Maris, after the stress of breaking Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record, changed his batting style the following year to avoid reliving the experience. Plimpton devotes a chapter in One for the Record to the pitchers who allowed the most famous home runs in baseball history. Ralph Branca tells him that, after yielding “The Shot Heard Round the World,” he left the Polo Grounds to find his sobbing fiancée waiting for him in the parking lot with a priest. Branca’s second career, Plimpton notes, was in life insurance.•