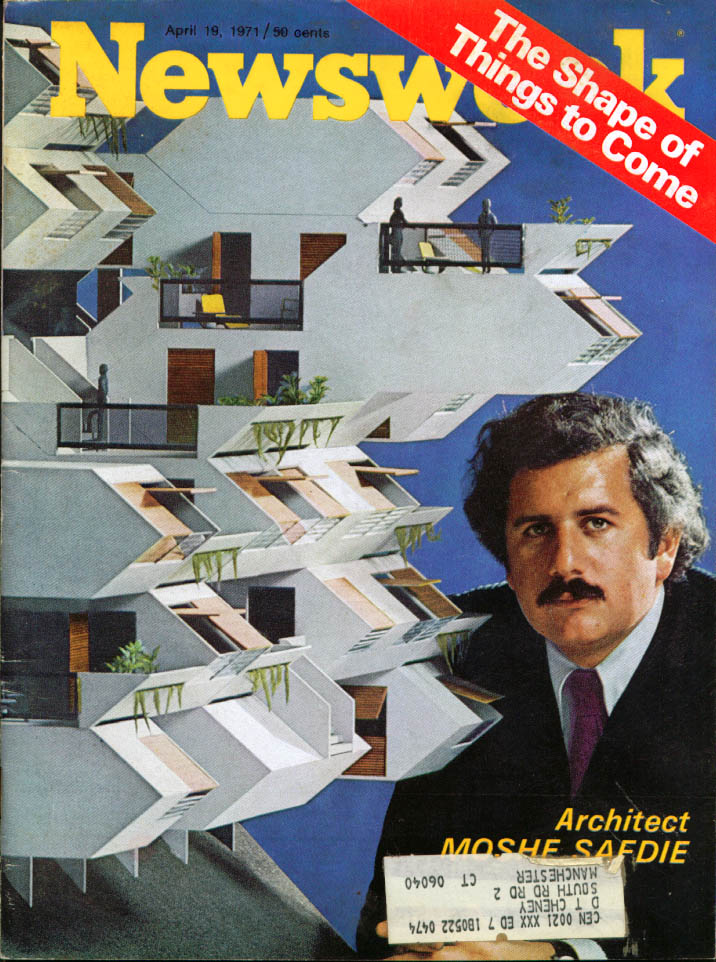

Almost a decade before the 1976 Olympics put Montreal in long-term debt, the city offered another large-scale gift: Expo 67, a world’s fair held just as such gatherings were beginning to become passé in a more-connected globe. One lasting monument to urban utopianism bequeathed by that event is Habitat 67, a controversial experiment in future-forward, communal-ish apartment living which sprang from the imagination of young Canadian-Israeli architect Moshe Safdie, like a kibbutz from the future being teleported to the present. Of course, it’s a future that’s never arrived. From Genevieve Paiement at the Guardian:

Habitat 67 echoes a little known post-war Japanese architectural movement called Metabolism, whose proponents believed buildings should be designed as living, organic, interconnected webs of prefabricated cells. Perhaps the most famous Metabolist incarnation is Tokyo’s Nakagin Capsule Tower, another pile of concrete cubes dotted with porthole-like windows, erected in 1972. The influence of Le Corbusier, especially the French master’s love affair with concrete, on Habitat 67 is also clear. But Safdie set his own course, attempting to balance cold geometry against living, breathing nature.

It was while travelling across North America as a student that Safdie surveyed grim apartment high-rises and unsustainable suburban sprawl. He returned home to Montreal with a mission: to “reinvent the apartment building”. He longed to create, as he put it in a 2014 Ted Talk, “a building which gives the qualities of a house to each unit – Habitat would be all about gardens, contact with nature, streets instead of corridors” (each cube has access to a roof garden built atop an adjacent cube).

Habitat 67 was a pilot project, intended as just the first application of a salve for urban ills that would spread across the world. Only it didn’t quite work out that way. The Walrus, Canada’s answer to the Atlantic magazine, called Habitat 67 a “failed dream.” …

The concrete needed frequent repair. One former resident, who lived there more than a decade ago for three years (and stilll prefers to remain anonymous, lest he offend the building’s diehard cheerleaders), says he fled after developing asthma and finding his cat dead. “From an architectural point of view, it’s spectacular, but water got into that concrete, and mould seeped into the ventilation system. It blew the spores around.” By the mid-1980s, the building was in private hands.•