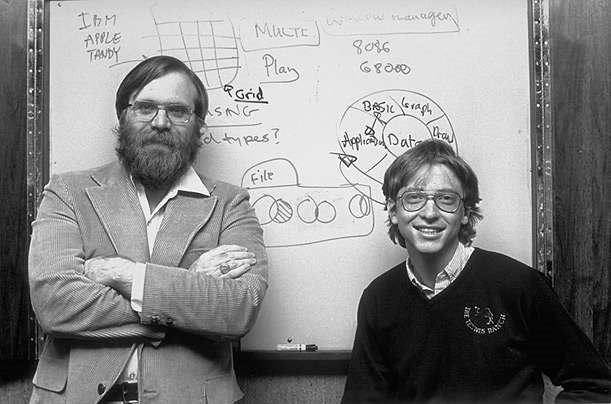

I haven’t yet read Walter Isaacson’s new Silicon Valley history, The Innovators, but I would be indebted if it answers the question of how much Gary Kildall’s software was instrumental to Microsoft’s rise. Was Bill Gates and Paul Allen’s immense success built on intellectual thievery? Has the story been mythologized beyond realistic proportion? An excerpt from Brendan Koerner’s New York Times review of the book:

“The digital revolution germinated not only at button-down Silicon Valley firms like Fairchild, but also in the hippie enclaves up the road in San Francisco. The intellectually curious denizens of these communities ‘shared a resistance to power elites and a desire to control their own access to information.’ Their freewheeling culture would give rise to the personal computer, the laptop and the concept of the Internet as a tool for the Everyman rather than scientists. Though Isaacson is clearly fond of these unconventional souls, his description of their world suffers from a certain anthropological detachment. Perhaps because he’s accustomed to writing biographies of men who operated inside the corridors of power — Benjamin Franklin, Henry Kissinger, Jobs — Isaacson seems a bit baffled by committed outsiders like Stewart Brand, an LSD-inspired futurist who predicted the democratization of computing. He also does himself no favors by frequently citing the work of John Markoff and Tom Wolfe, two writers who have produced far more intimate portraits of ’60s counterculture.

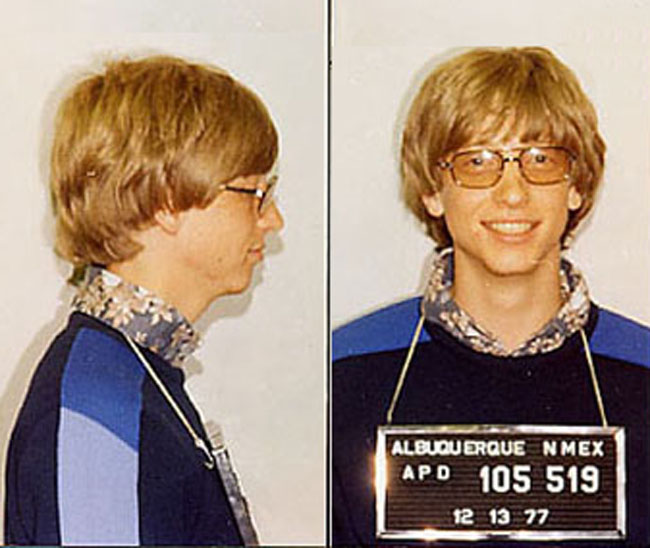

Yet this minor shortcoming is quickly forgiven when The Innovators segues into its rollicking last act, in which hardware becomes commoditized and software goes on the ascent. The star here is Bill Gates, whom Isaacson depicts as something close to a punk — a spoiled brat and compulsive gambler who ‘was rebellious just for the hell of it.’ Like Paul Baran before him, Gates encountered an appalling lack of vision in the corporate realm — in his case at IBM, which failed to realize that its flagship personal computer would be cloned into oblivion if the company permitted Microsoft to license the machine’s MS-DOS operating system at will. Gates pounced on this mistake with a feral zeal that belies his current image as a sweater-clad humanitarian.”