In a 1946 issue of Collier’s Weekly, journalist, publicist and space-travel enthusiast G. Edward Pendray penned “Next Stop the Moon,” a piece about establishing lunar settlements not to build some Gingrich-ian theme park but for permanent settlements and trade routes, using Columbus, not Disney, as his lodestar. An excerpt about financial considerations:

What Profit in Lunar Conquest?

Perhaps the foremost question now is: Why attempt a trip to the moon? What will the explorers be looking for?

When Columbus approached Queen Isabella about supporting his voyage to the New World, he had some rather tangible inducements to offer. There were the much-talked-of new trade routes for the spices and other products of the East. There was, of course, the possibility of new knowledge, prized by scholars. More appealing to sovereigns both then and now, there was also the promise of wealth and power.

The same inducements, though on a larger, more modern scale, beckon to the sponsors of a pioneering voyage across space’s vast unknowns. There may be no spices on the moon, but as we shall see, the moon is a key point in future trade routes with the planets. Who knows what 21st century equivalents of rare spices will ultimately be discovered on them?

For the scholars, there will certainly be much new knowledge in the special venture. In fact, discovery of new knowledge must begin even before the journey starts. Lots of it will be required to build a vehicle to take explorers across the void.

Wealth? Gold isn’t as much prized in these times as formerly, but uranium is now an even more precious metal and there are good—or at least interesting—arguments for the possibility of large deposits of uranium ind other radioactive metals on the moon.

Power? Our satellite, by its position, size and other advantages, is the natural watchman of the crossroads of space. Its gravitational attraction is so small that rockets only a little faster than the German V-2s could bombard the earth from the moon. With the aid of suitable guiding devices, such rockets could hit any city on the globe with devastating effect. A return attack from the earth would require rockets many times more powerful to carry the same pay load of destruction; and they would, moreover, have to be launched under much more adverse conditions for hitting a small target, such as the moon colony.

So far as sovereign power is concerned, therefore, control of the moon in the interplanetary world of the atomic future could mean military control of our whole portion of the solar system. Its dominance could include not only the earth but also Mars and Venus, the two other possibly habitable planets.

Whether permanent colonies could be founded on the moon might depend on whether uranium or other practical sources of atomic energy are discovered. On the earth, uranium seems to be concentrated mostly in the outer crust. The moon, some astronomers believe, was once a part of that crust, having been thrown into space out of the pit where the Pacific Ocean now rolls, during a violent paroxysm in the earlier history of our globe.

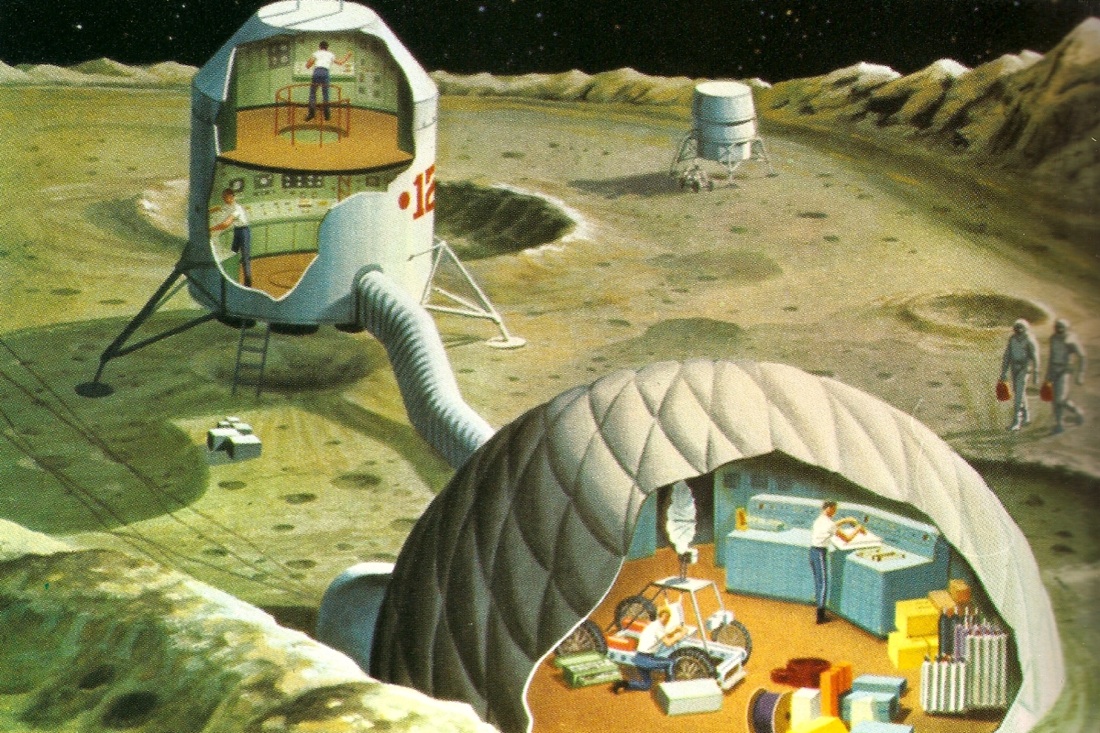

It is possible, therefore, that our satellite, being composed entirely of earth’s crustal materials, may be relatively rich in uranium. Should this turn out to be a fact, it would be simple to construct reacting atomic “piles” on the moon like those of the Manhattan Project, only bigger. These could produce heat for melting lunar sand into thick glass slabs, which would be employed for constructing an airtight roof over a crevice or one of the small craters. Atomic piles could furnish power to heat, light and aircondition a small city in such a sheltered place. The power might even enable chemists to extract oxygen, hydrogen and nitrogen from lunar minerals to create a water supply and an adequate atmosphere in the domed city.

Obviously establishing a moon colony will take some doing. It will not be accomplished by the first rocket ship to visit the premises. There will have to be at least four stages to the process of conquering the moon—each step probably consisting of several abortive trials before attaining success. Assuming rockets capable of shooting away from the earth, the four stages may be these:

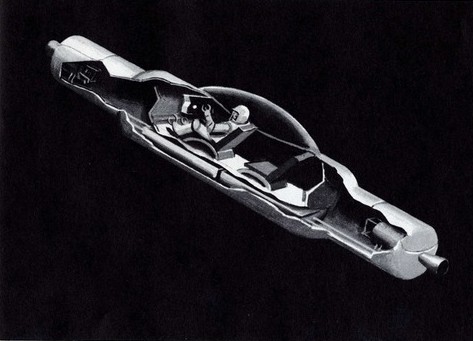

1. The Target Shots. Unmanned instrument-carrying rockets will be sent first, to test out flight calculations and controls. They will carry self-operating radio-equipped instruments to provide preliminary information about the range of temperatures, radiation, gravitational influences and other conditions to be encountered on the journey and on the lunar surface. These instrument-carrying rockets will not be equipped to return. They will land on the moon and transmit continuous automatic messages back to earth as long as their power supply lasts.

2. The Pilot Expedition will be the first manned space rocket. It will carry a crew of perhaps five, with all necessary equipment. Its mission: to spend a lunar day and night—28 earth days—on the moon, gathering all data possible in the allowed period, then returning to the earth. The crew probably will consist of a pilot-navigator, a copilot and mechanic engineer, a medical man, a physicist-chemist who is also a radio and radiation expert, and a geologist-mineralogist. These five will be selected not only for unusual skill and proficiency in their several technical fields, but also for resourcefulness, physical hardiness, courage and ability to observe.

3. The Moonhead Expedition will be the first small group of pioneers assigned to a settlement on the moon. Its size, make-up and equipment will depend on what is learned by the Pilot Expedition, but may consist of perhaps ten men, supplied at regular intervals by additional cargo rockets, either unmanned and robot-controlled, or staffed with small crews. Regular two-way communication and supply connections may be started in this way between the earth and moon.

4. Full Colonization, the final phase. It will begin after the Moonhead Expedition has established a firm foothold. The original small settlement will be increased in size and conditions established for fairly normal life, considering the natural difficulties. A few especially courageous women may join their men in this phase, though it is not to be expected that anybody will remain on the moon for protracted periods. Colonists will probably take regular turns of service, alternating with periods of rest and recuperation at home on earth.•