We don’t know we’re ridiculous, so it hurts when someone points it out.

That harsh realization, however, is seldom enough to claim a life. Perhaps Dr. Fredric Brandt, the dermatologist to the stars known as the “Baron of Botox,” was really so deeply wounded by Martin Short’s cutting Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt caricature of his Bond villain otherworldliness that it pushed him to suicide, but it was likely more complicated. Dr. Brandt had long suffered from bouts of depression (perhaps stemming from his orphaned childhood or some biochemical origin) and was said to be no stranger to loneliness. He probably wanted to fix himself on the inside where it hurt, but he had to settle for working on his face, trying to force his lips upward into a smile. From the Economist:

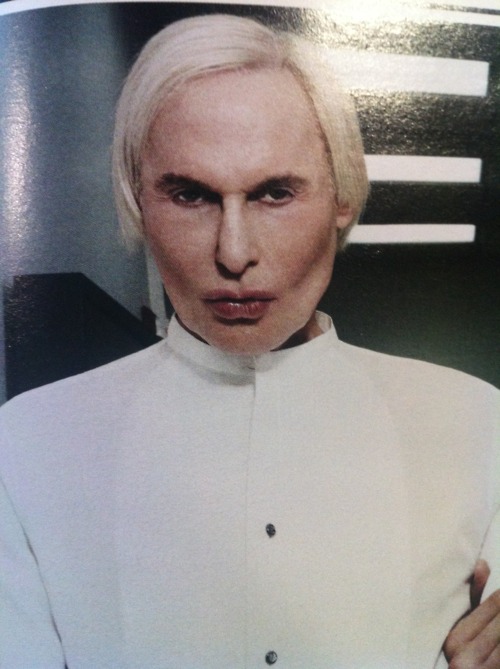

He liked to call himself a sculptor of faces. But he did not cut or chisel. That was the work of the plastic surgeons who had pioneered beauty treatment, sawing away outsize noses and tightening withered skin over unforgiving cheekbones, via a general anaesthetic, scars and bruising. He did not criticise his sawbones colleagues, but he thought his own countenance showed that the needle worked better than the knife. Visitors sceptical of his strangely smooth skin would be invited to check behind his ears for the telltale signs of a facelift.

Some thought his strange appearance exemplified the cost of battling the years. His pneumatic features and eerie complexion could seem repellent: an alien doctor from a visiting starship, perhaps. Others thought his wispy blond hair and fair skin might be a sign of Scandinavian roots. He laughed at that: he was a Jewish orphan whose parents had run a confectionery shop in Newark; his appearance was a triumph, just like his career.

Critics muttered that the “Skincare Svengali”, (as Vogue dubbed him, appreciatively), was engaged in a nightmarish science project, making a fortune from human weakness. Better, surely to grow old gracefully and naturally. But his patients saw it differently. They wanted to feel better about themselves, to remember the people they had been—and to stay competetive in a society that prizes only youthful beauty. Laurin Sydney, a television journalist, said he helped her extend her career 18 years after her “sell-by date”. Madonna told the New York Times: “If I have nice skin, I owe a lot to him.”•