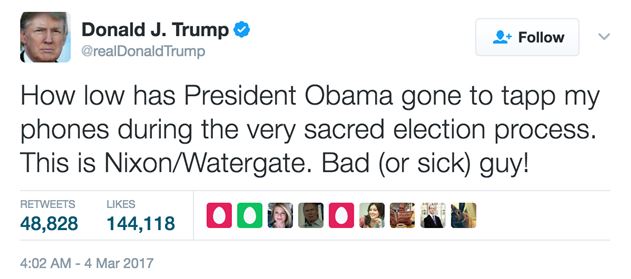

The “tapp my phones” charge Trump leveled against President Obama on Match 4 in an angry tweet seemed bizarre at first but so initially did the neophyte politician’s defense of the nation’s tyrannical adversary Vladimir Putin during the campaign. The two strange episodes are likely deeply intertwined.

The support of Putin appears now to have been compensation for Russia hacking the election, and not because of some supposed lurid recording of a Moscow pee party. The current wiretapping tale Trump is spinning might just be spasms of his usual ugly ego or it may be an effort to preempt what’s coming next, with the Administration having probably already been informed about the existence of FBI tapes that could prove deeply damaging or even take down the whole operation. Were illicit activities coordinated between Trump Tower and the Kremlin? Was Russian money illegally funneled into the campaign? It’s not clear yet, but the behavior of the new President and his cohort makes these questions worth asking. Something major could be on the horizon.

· · ·

In a Politico piece, Francis Fukuyama crows a bit about a prediction he offered in January, when he argued that our checks and balances would thwart this aspiring autocrat. He argues that so far his forecast has proven true, using the failed Obamacare repeal as his prime example.

His larger contention may ultimately stand as correct, but wasn’t the AHCA debacle less the work of our democracy’s efficacy than of Republican dysfunction and White House ineptitude? The writer acknowledges as much, but goes on to assert that gerrymandering, a political system guided by outside money and Freedom Caucus members fearing Tea Party fury turned out to be blessings (before pointing out is in his final paragraph how unhealthy this situation). The Oval Office’s inability to torpedo the ACA is really more the result of odd and unhappy circumstances, of sickness rather than health. And a potential despot who didn’t possess the attention span of a small child would have had a strong shot to make this bill of goods stick.

If we look at Trump’s attempts to undermine the press and neutralize other levers of the government, the legislative branch has been a great disappointment in regards to checking his power, with Congress working to obstruct investigations into the deeply shady behavior of the Administration during the campaign and since. The judicial branch has been reliable and the media mostly so, but the House has been pretty much complicit in the Presidential power grab and kleptocracy, even if it’s too much of a mess to get out of its own way on the policy it has long prioritized.

Fukuyama is probably right that Trump will fail to bend the system to his will, but it’s worth wondering what a hyper-competent version of him could accomplish.

The opening:

Back in January, I argued in these pages that whatever President Donald Trump’s proclivities toward being a strongman ruler, the American system of checks and balances in the end had a good chance of containing him. Friday’s failure of the Republican attempt to repeal Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act underscores how difficult our political system makes any kind of decisive political action. During Obama’s presidency, House Republicans voted some 60 times to repeal parts or the whole of the ACA, and Trump himself pledged that he would replace it with “something wonderful” on Day One of his administration. And yet it appears the ACA will continue to be, as House Speaker Paul Ryan admitted, “the law of the land.” This happened despite the fact that we no longer have divided government, with the Republicans controlling both houses of Congress and the presidency.

The fundamental reason for the failure of the American Health Care Act lies, of course, in the internal divisions within the Republican Party. The bill was extremely unpopular from the beginning due to the fact it would have potentially resulted in 24 million fewer Americans having health insurance, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The Democrats, though a minority, were therefore uniformly opposed to repeal, meaning that the Republicans could afford only 26 defections for the legislation to fail. The hard-line Freedom Caucus in the end could not be badgered or threatened to accept “Obamacare Lite,” coming, as many of them do, from safe, gerrymandered districts.

This is where the mounting number of institutional checks within the American system came into play. Had this vote been held 75 years ago, the powerful committee chairmen in the House, together with the Republican Party leadership, could have corralled these renegades through a combination of bribes or threats. Today, such tools do not exist: Earmarks have been eliminated along with the powers of the committee chairs, and there is too much money from groups outside the control of the party hierarchy. The Freedom Caucus holdouts were much more frightened of a Tea Party challenge in the primaries than they were of either Paul Ryan or Donald Trump.•