Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation is the “little” 1974 psychological thriller he squeezed in between the first two Godfather films, which fast-forwarded the disquiet of Antonioni’s Blow-Up into the Watergate Era, even if the director has always considered it more a personal than political film. The movie, which hangs on San Francisco surveillance expert Harry Caul’s descent into madness, remains a classic and has actually grown in stature as the Digital Age replaced the analog one. When I wrote briefly about the cerebral movie six years ago, I concluded with this:

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation is the “little” 1974 psychological thriller he squeezed in between the first two Godfather films, which fast-forwarded the disquiet of Antonioni’s Blow-Up into the Watergate Era, even if the director has always considered it more a personal than political film. The movie, which hangs on San Francisco surveillance expert Harry Caul’s descent into madness, remains a classic and has actually grown in stature as the Digital Age replaced the analog one. When I wrote briefly about the cerebral movie six years ago, I concluded with this:

In the era that saw the downfall of an American President who listened to the tapes of others and erased his own, The Conversation was amazingly relevant, but in some ways it may be even more meaningful in this exhibitionist age, in which we gleefully hand over our privacy to satisfy our egos. As Caul and Nixon learned, and as we may yet, those who press PLAY don’t always get to choose when to press STOP.•

This weekend, we had a sitting American President (baselessly) accuse his predecessor of tapping his phone lines, all the while the Intelligence Community searches for real tapes of this Administration’s officials conspiring with the Kremlin during the campaign. Such evidence would be treasonous.

It’s not shocking that Trump’s viciously ugly brand of nostalgia has forced us backwards into a Cold Way type of paranoia, in which 20th-century espionage is predominant. The greater insight to take from The Conversation may be more about the near future, however, when nobody has to hit PLAY because there’s no longer a STOP.

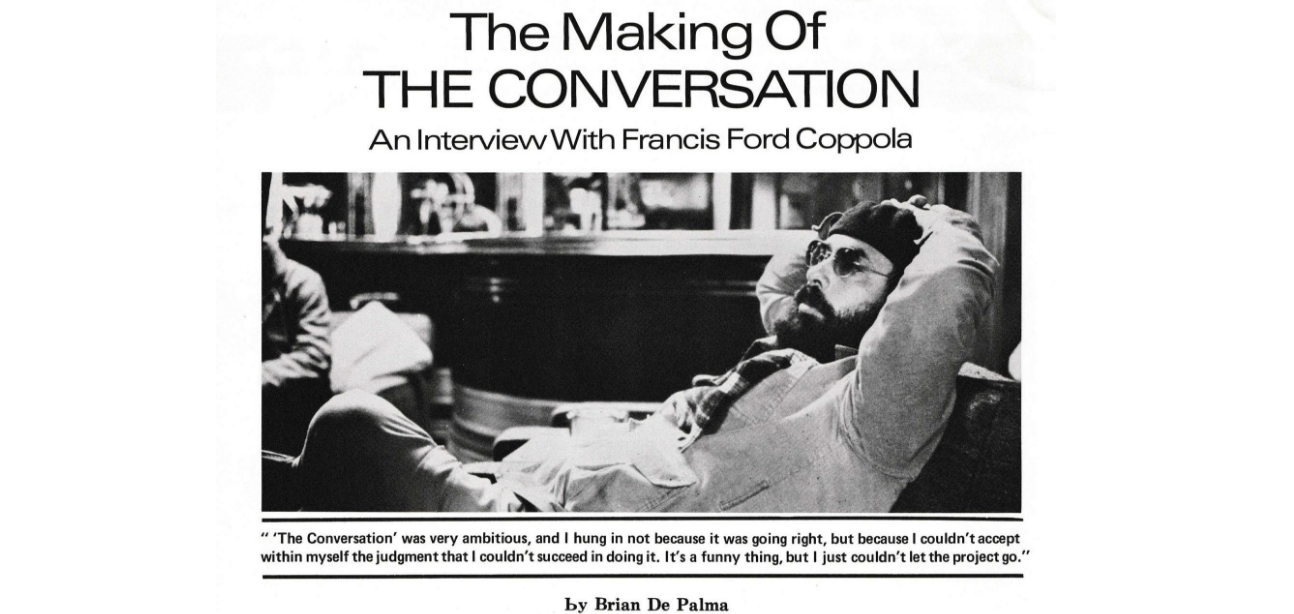

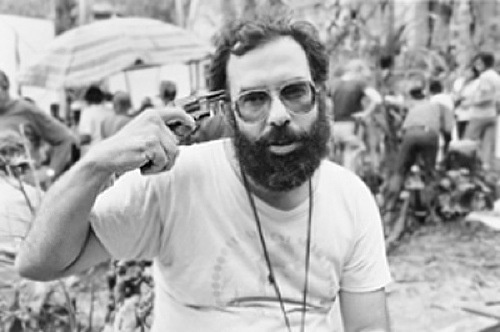

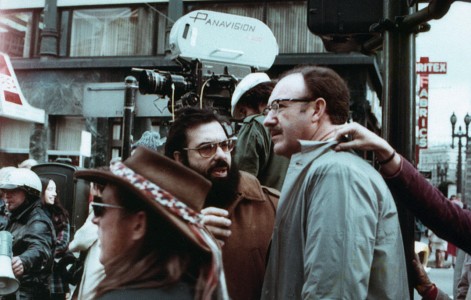

In an amazing find, the good people at Cinephilia & Beyond published a 1974 Filmmakers Newsletter interview in which Brian De Palma quizzed Coppola about this masterwork. It’s more a discussion of cinema than of Watergate, and there’s a very interesting exchange in which the subject reveals why he doesn’t regard Hitchcock with awe.

Here’s the opening:

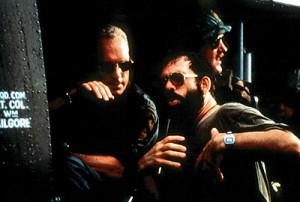

Here’s a wonderful making-of featurette about The Conversation, which asked questions about a world where everyone is a spy and spied upon. The surprise more than 40 years later: Few seemed upset as we crept into the new order of the techno-society. We haven’t been trapped after all; we’ve logged on and signed up for it.