Are the people finally tired of bread and Kardashians?

The radical American political movements of this millennia–Tea Party, Occupy Wall Street, #MAGA and #Resist–have many parents, but each extreme reaction seems rooted in a widespread and often inexpressible dissatisfaction with what’s become of U.S. democracy. That angst has the potential to lead to good or bad.

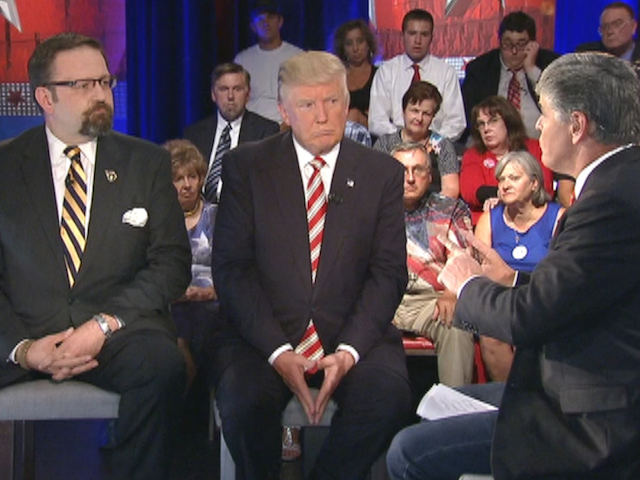

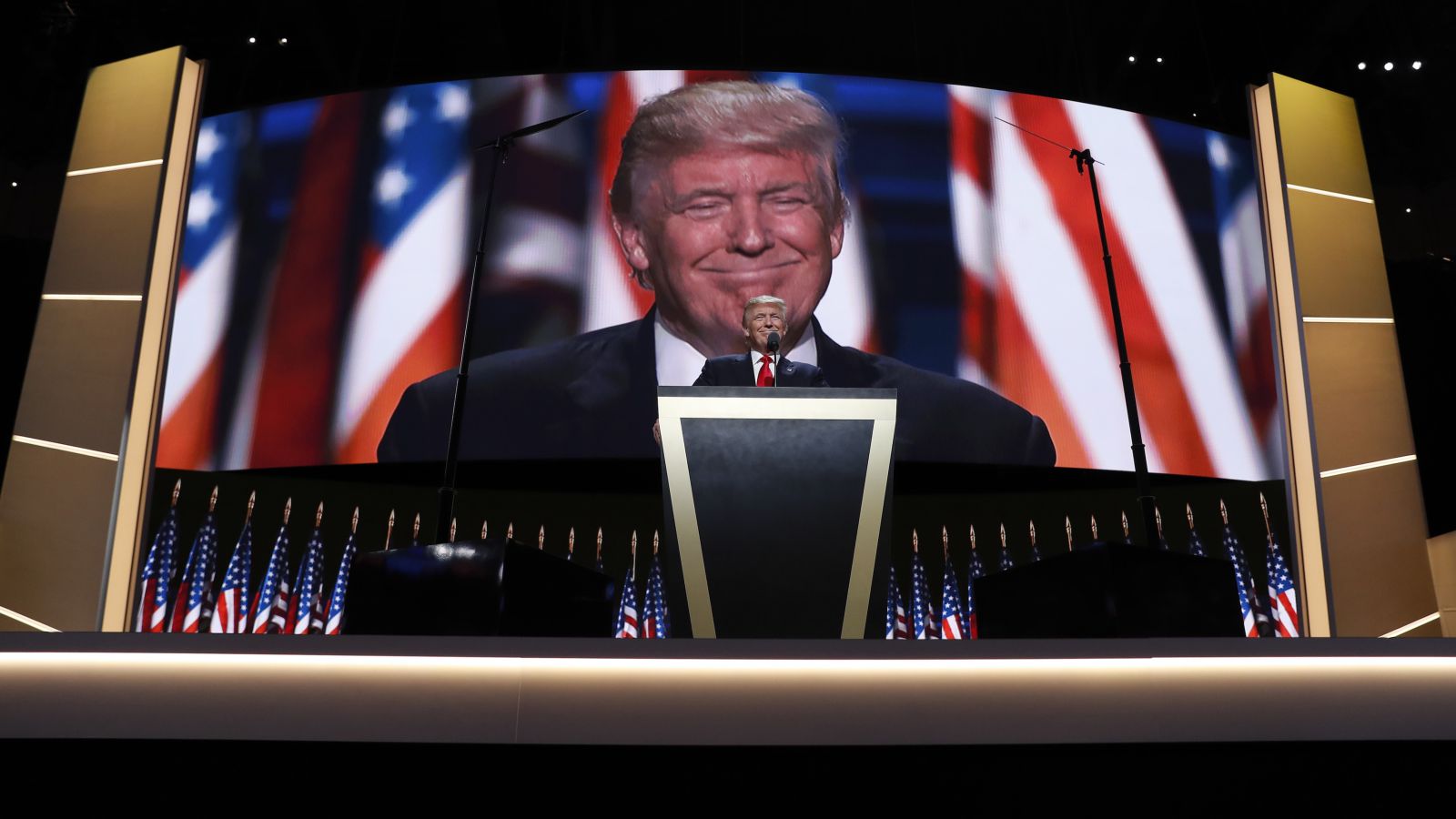

It allowed for the election of a faux populist like Trump, a Berlusconi who dreams of being a Mussolini, and maybe according to the puzzling Sarandon playbook, it will end with a flood of indictments that will bring down what seems more and more to be a compromised White House, with a money-soaked capital coming tumbling after.

Or, more darkly, we might ultimately experience an age as exciting as the 1930s. Considering how splintered we are, we could be ripe for such a despoliation.

In a really smart Playboy Interview, David Hochman asks Ezra Klein, who explains things, to make sense of our new abnormal. The catch is, there’s no clear path forward, just many roads riddled with pointy forks. An excerpt:

Question:

Since the election, conspiracy theories have shifted from conservatives digging up things on Hillary Clinton’s e-mails to progressives obsessing over Donald Trump’s scandals and corruption. What’s your political paranoia level these days?

Ezra Klein:

I must admit, I am in general not a conspiracy theorist, but I feel Trump is doing his damnedest to turn me into one. This administration sure seems to be covering a lot up and willing to take a lot of damage to not reveal what it is they’re covering up. When you watch that happen over and over again on the tax returns or on the Russia stuff, at some point you’re not a conspiracy theorist to think there’s something concerning in there. They could easily say, “This is clearly all bullshit. Let’s just appoint a prosecutor and get it out there. Let’s move on.” But that’s not the case. Even on the tax returns, how hard would it be to say, “Okay, we gave the returns to an independent group. They looked at them. Everything’s fine.” It makes you suspicious.

Question:

And why don’t people care?

Ezra Klein:

I think people do care.

Question:

Not enough to be storming the gates at the White House. I walked by this morning, and there was one homeless vet in a wheelchair with a sign that said need weed money. That was it.

Ezra Klein:

I think about this in two ways. First, don’t underestimate how unprecedented the political mobilization has been so far in the Trump era. There have been a ton of protests—in some cases the biggest single-day coordinated protests ever. Compared with a typical honeymoon run for a first-term president, people absolutely care. They’re showing up at Republican town halls, they’re organizing, they’re flooding congressional phone banks, they’re out there with pink pussy hats.

Question:

David Brooks calls it a lot of liberal feel-goodism.

Ezra Klein:

That’s just not the case. Being politically active is not feel-goodism. If nothing else, it’s a powerful message that dissent will be a constant part of this era in American politics, as it should be of every era in American politics, as the Tea Party was to Obama—though I don’t think Obama had quite the same tendencies to delegitimize as Trump does. Organizing is powerful, and a lot of that organizing is now turning its attention to members of the House and the Senate. They listen, they’re accountable, and they come up for reelection. Every voting member of the House is up for reelection in 2018, and the groundswell against Trump is already influencing the choices those legislators are making.

At the same time, caring can be binary. Either you’re uninterested or you need to literally be dodging snipers on the White House lawn. People care, but they have lives. When you leave this interview you’ll probably go home, not throw rocks over the White House gate. People cared enough to vote against this guy—not enough people in the places where it counted but enough to have him lose the popular vote pretty decisively. We haven’t yet seen what protests can do.

Question:

Do you ever worry about being a journalist in these polarized times?

Ezra Klein:

I do. All the time. I think things could go in very dark directions.•