Before cars or even bicycles were perfected, there were walking machines like the Aeripedis, or Pedomotive Carriage. They aimed to remove much of the strain of ambulation though, of course, the process still had to be manged by your brain.

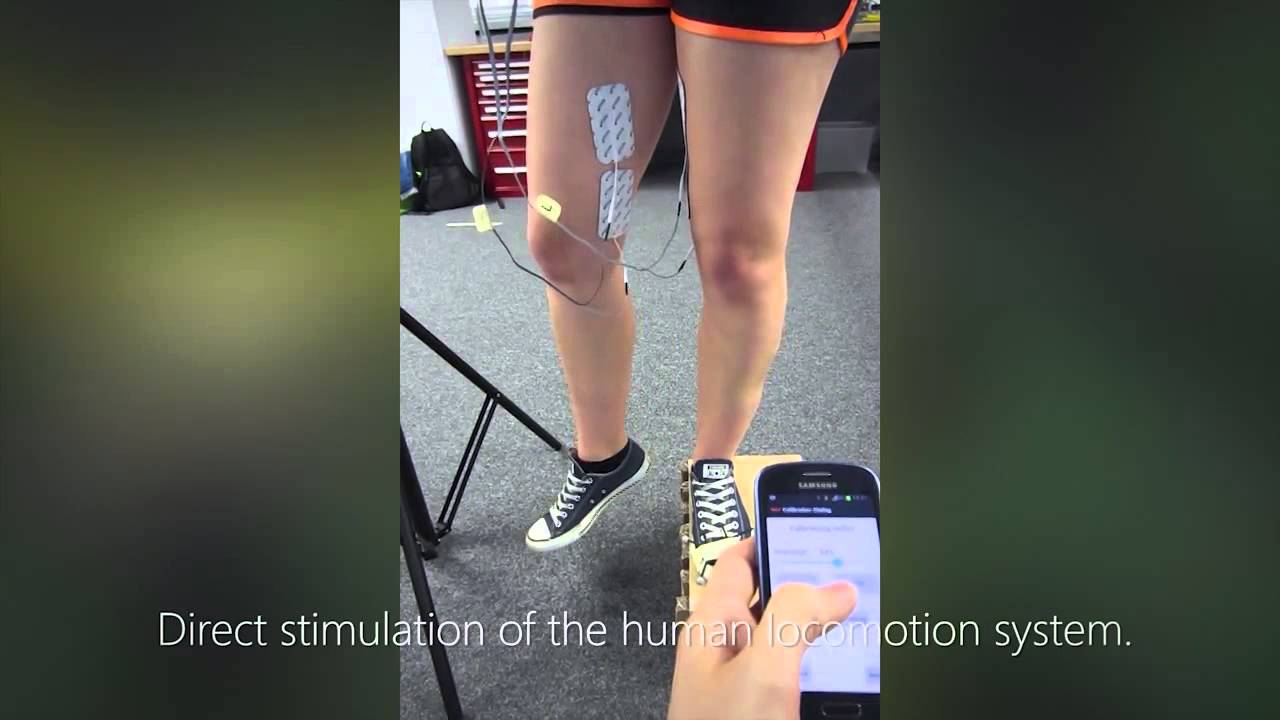

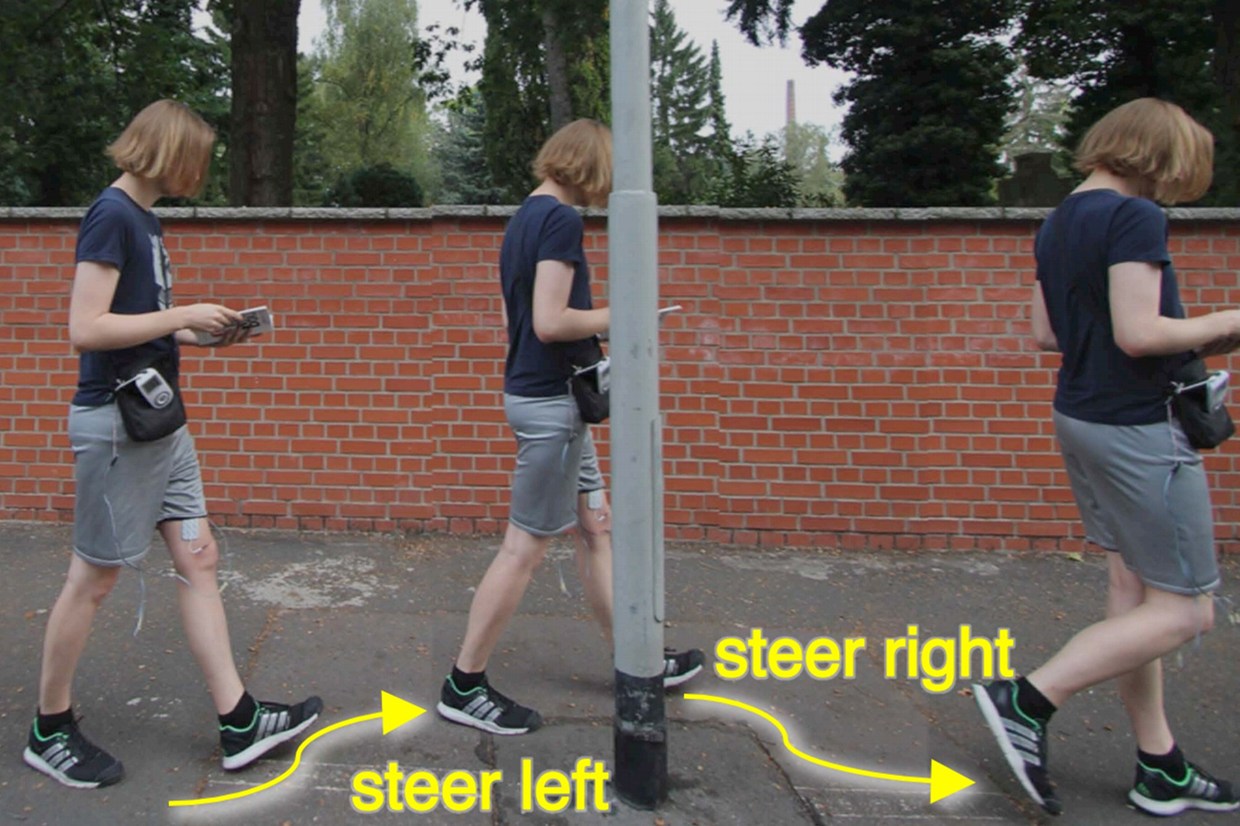

When I heard about Max Pfeiffer’s “cruise control for pedestrians” last month, I thought at first it might be an April Fools’ Day joke, but that’s not the case. The system combines smartphone GPS and electrodes attached to your legs to offload your navigational responsibilities to the cloud. More or less, it’s “automated walking,” and the movements can be remotely directed by another party. If you’re someplace unfamiliar and don’t know what direction in which to head, actuated navigation can do the thinking for you, guide your every step.

At Wired UK, Evan Selinger argues that the scheme is a road to hell. An excerpt:

In order to truly get a handle on the significance of “actuated navigation,” we need to do more than just imagine rosy possibilities. We’ve also got to confront the basic moral and political question of outsourcing and ask when delegating a task to a third party has hidden costs. To narrow down our focus, let’s consider the case of guided strolling. On the plus side, Pfeiffer suggests that senior citizens will appreciate help returning home when they’re feeling discombobulated, tourists will enjoy seeing more sights while freed up by the pedestrian version of cruise control, and friends, family, and co-workers will get more out of life by safely throwing themselves into engrossing, peripatetic conversation. But what about the potential downside?

Critics have identified several concerns with using current forms of GPS technology. They have reservations about devices that merely cue us with written instructions, verbal cues, and maps that update in real-time. Nicholas Carr warns of our susceptibility to automation bias and complacency, psychological outcomes that can lead people to do foolish things, like ignoring common sense and driving a car into a lake.Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Kelly lament that it’s “dehumanising” to succumb to GPS orientation because it “trivialises the art of navigation” and leaves us without a rich sense of where we are and where we’re going. Both of these issues are germane. But while, in principle, technical fixes can correct the mistakes that would erroneously guide zombified walkers into open sewer holes and oncoming traffic, the issue of orientation remains a more vexing existential and social problem.

Pfeiffer himself recognises this dilemma. He told WIRED.co.uk that he hopes his technology can help liberate people from the tyranny of walking around with their downcast eyes buried in smartphone maps. But he also admitted that “when freed from the responsibility of navigating…most of his volunteers wanted to check email as they walked.” At stake, here, is the risk of unintentionally turning the current dream of autonomous vehicles into a model for locomotion writ large.•

__________________________________

“Actuated navigation is a new kind of navigation, reducing cognitive load.”